Why foreigner verification is under scrutiny

Some foreign nationals can secure South Korean mobile phone service before they even arrive, using only a copy of a passport to start the process. The convenience is obvious for workers and students planning a move, yet the practice bypasses the tighter verification that citizens face. A program marketed by a major carrier allowed overseas applicants with certain visas to register in advance and activate service the moment they land. Lawmakers and investigators say the gap is real and growing, and criminals are quick to exploit it.

- Why foreigner verification is under scrutiny

- How the system works for locals versus foreign nationals

- KT’s overseas signup program and a regulatory blind spot

- What competitors require

- From loophole to crime pipeline

- Regulators and police respond

- Technical fixes that could help

- Balancing access for newcomers with fraud prevention

- What other countries are doing

- What to Know

People Power Party lawmaker Choi Hyung-du raised the alarm after reviewing data obtained from the Korea Communications Commission. His office says the practice leaves core identity checks for foreign nationals to corporate discretion. The concern is not abstract. Police say burner phones registered under foreign names have surged from 474 cases in 2019 to more than 71,000 in 2024. Voice phishing scams have already drained about 800 billion won by July this year, and authorities expect losses to top 1.37 trillion won by year end. Weak verification at the point of mobile registration makes these crimes easier to set up and harder to trace.

How the system works for locals versus foreign nationals

South Korea requires identity verification for every new mobile subscription. For citizens and long-term residents, retailers scan a government ID and run an automated anti forgery check. That system compares security features and data fields to detect tampering. It creates a reliable baseline for mobile services, banking apps tied to phone numbers, and the country’s real name communications environment.

Foreign nationals face a different path. The rules that carriers follow are less specific, and practices vary by company and by storefront. Many outlets accept a passport image, then perform a visual match against the customer, with no digital confirmation of authenticity. Some shops ask for more documents, others do not. In effect, the strength of verification can depend on the seller, not a standard national system. That variability is the loophole lawmakers want to close.

KT’s overseas signup program and a regulatory blind spot

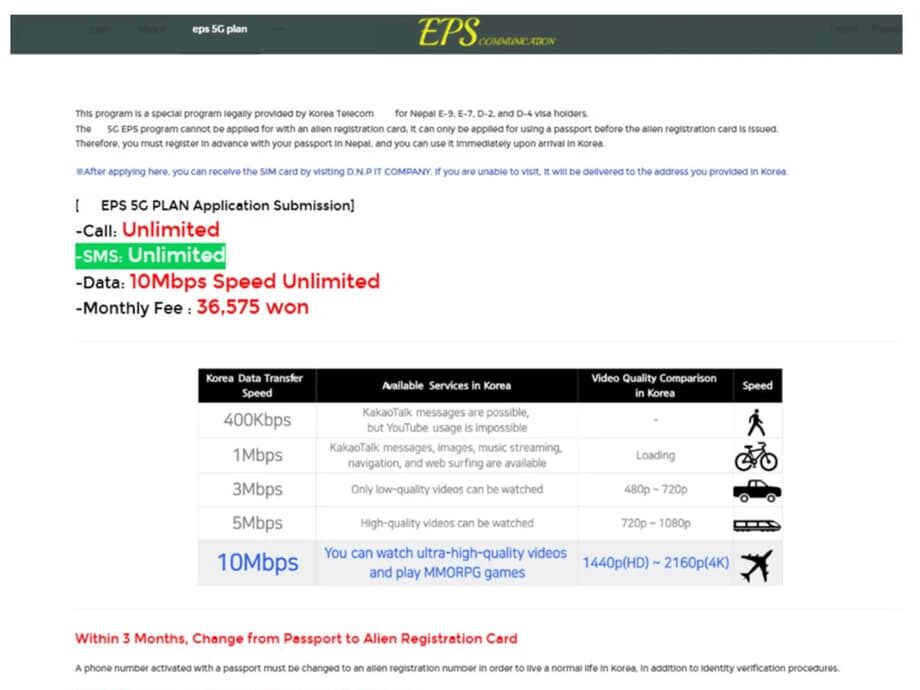

One major operator, KT, marketed a 5G postpaid plan to visa holders outside Korea. The offer let applicants in countries such as Vietnam and Nepal register before travel by submitting a passport copy. For specific visa categories, including E7 and E9 for workers and D2 and D4 for students, the company accepted a single passport copy, charged a monthly fee of 36,575 won, and promised immediate service upon arrival in Korea. Brokers promoted the option and collected passport images from people preparing to move.

KT says foreign customers are re verified once they obtain their Residence Cards, and that the overseas SIM service is formally approved by the Ministry of Science and ICT. Company officials also say they cross check other documents such as employment contracts or university admission letters to confirm identity. Those extra steps, however, do not appear in KT’s publicly posted service terms, which has fueled debate about how the process works in practice.

Choi’s legislative aide Park Jae-sung argues that basic safeguards should not hinge on voluntary policies.

Park Jae-sung, legislative aide to Rep. Choi Hyung-du: “The loophole should never be left to company policy but must be addressed by law.”

The question for regulators is how to align business convenience with uniform checks that are hard to bypass, even when registration occurs outside the country.

What competitors require

Competitors take a more conservative approach. SK Telecom requires a Residence Card for foreign nationals who want a postpaid line. It applies separate procedures for diplomats, US military personnel, and overseas Koreans, groups that carry different identity documents.

LG Uplus accepts passports for foreign customers, yet it also requires supplemental paperwork and in person identity verification. Typical documents include a standard employment contract for E7 and E9 visa holders or an admission letter for D2 and D4 visa holders. The customer must appear in person so a staff member can verify the individual against the documents. These steps raise the verification bar and reduce the odds that a fake identity slips through.

By comparison, KT’s acceptance of a single passport copy for specific visa holders and its prearrival processing introduce a point of weakness. That approach makes it easier for a bad actor, or a broker working with stolen documents, to obtain an active number that looks legitimate on day one.

From loophole to crime pipeline

Recent police work shows how fast a soft spot in ID checks can turn into a crime pipeline. Investigators identified 71 people tied to a scheme that used more than 11,000 ghost SIM cards registered with passport copies of foreign nationals living in Korea. At least nine suspects were arrested, including the owner of multiple phone shops in central Seoul. According to police, the SIMs enabled voice phishing, drug transactions, and illegal lending. The setup gave criminals anonymous phone numbers, a core tool for hiding the origin of calls and messages.

Investigators say the group acquired passport scans through the encrypted messaging app Telegram and then used them to activate SIMs at 18 retail stores nationwide. Seven employees at two mobile virtual network operators were allegedly involved, approving activations based on photocopies and fabricated application forms. Each SIM sold for between 200,000 and 800,000 won, with estimated profits of about 1.6 billion won. The suspected ringleader collected around 30,000 won per SIM as a commission.

Police seized more than 3,400 forged application documents and over 400 SIM cards, froze 730 million won in suspected criminal proceeds, and requested the cancellation of 7,395 phone lines. Authorities link at least 1,400 of the ghost SIMs to voice phishing or large fraud cases. National Police Agency figures show the scale of the harm. Average losses per victim reached 41 million won in 2024, and nationwide losses hit a record 854.5 billion won. The steep rise in burner phones under foreign names, from hundreds to tens of thousands in only a few years, is a red flag that the current safeguards are not working as intended.

Regulators and police respond

The government introduced national level measures to harden SIM registration. New rules rolled out in August require biometric checks for SIM registration. Carriers now limit foreign passport holders to one line, and authorities plan to hold telecom companies responsible for repeated illegal activations that occur under their watch. These measures change the incentives. Strong identity checks become a compliance requirement, not just a best practice.

Rep. Choi has also called for more structural fixes. He wants uniform ID requirements for all foreign national subscribers, direct links between telecom verification systems and immigration databases, better technology to detect forged documents, and tighter oversight of sales outlets that register a high volume of foreign customers. The aim is to convert a patchwork of company policies into a single standard backed by law and automated tools.

KT maintains that its overseas activation program has ministry approval and that customers are subject to re verification once they receive Residence Cards. The company says it often cross checks employment or enrollment documents. The friction point is whether those checks are consistently performed, and whether they occur early enough to block misuse before a number goes live.

Technical fixes that could help

Biometric verification and liveness checks can raise the bar for remote onboarding. A simple photo of a passport is easy to copy or manipulate. A live facial scan matched to a high quality ID image, paired with liveness detection that defeats photos, videos or masks, makes impersonation far harder. This is how many banks verify new customers through a smartphone.

Document authentication should go beyond a visual inspection of a passport photo page. Modern passports include a machine readable zone and a contactless chip. Reading the chip and validating its digital signature through public key infrastructure confirms that the document was issued by a real authority and has not been altered. If a carrier accepts passports, it should require chip reads where available and automatically flag documents that fail integrity checks.

Back end integration is equally important. A real time connection to immigration data would allow a carrier to confirm visa type, validity dates, and entry records. For prearrival signups, a safer model would collect the application and reserve the phone number, then activate service only after the system detects the person has cleared immigration. Mismatches, expired visas, or multiple applications tied to one passport would trigger manual review before any line is turned on.

Compliance for MVNOs deserves specific attention. Fraud rings often target smaller operators and retail outlets with weaker controls. Requiring all MVNOs to use a common, certified verification pipeline, mandating independent audits, and enforcing consistent data logs would lift the baseline. Carriers could also apply dynamic risk scoring across new signups. Factors such as unusual volumes from one outlet, repeated use of the same address, or clusters of applications tied to the same broker would prompt additional checks or temporary holds.

Balancing access for newcomers with fraud prevention

Newcomers need working phones to get settled. Employers expect mobile contact. Universities use phone numbers to deliver campus notices and payment alerts. Cutting foreigners off from mobile service until they obtain a Residence Card can create real friction, especially when card issuance takes time after arrival. The policy challenge is to give legitimate users a safe on ramp while closing obvious gaps for criminals.

Several practical steps could help. Carriers can offer a limited prearrival plan with capped spending, no international transfers, and stricter call and data thresholds. Full service would unlock only after an in person check or a Residence Card is validated through an official API. A one number per passport rule should apply from the first day, with automatic lockouts when multiple attempts appear. If an employer or a university letter is used, the system should verify the document at the source, for example by checking a secure code against the institution’s system.

Consumer education matters too. Foreign residents should know that sharing a passport image can lead to unauthorized accounts, and that they can check for lines opened in their name. Clear instructions, in multiple languages, on how to report suspected misuse would reduce the time criminals have to exploit stolen credentials.

What other countries are doing

Thailand recently tightened SIM registration after a wave of telecom scams. The regulator introduced liveness detection for all new subscribers, both prepaid and postpaid, and for SIM replacements that keep an existing number. Users must present original documents, and foreigners submit passports while corporate accounts provide company certificates and proof of signing authority. The technology verifies a live face against an ID in real time, blocking static photos and deepfake attempts that once fooled staff. Operators must also comply with data protection rules that govern how identity information is stored and used.

Korea can draw a clear lesson from this regional example. Technology that binds a real person to a legitimate credential at the moment of signup, supported by automated checks against official records, is more robust than manual review at a sales counter. When combined with limits on the number of lines, stronger monitoring of high volume outlets, and penalties for repeated violations, it creates fewer openings for fraud without shutting out people who need a number to live and work.

What to Know

- A KT program let certain visa holders register abroad with only a passport copy, then activate service on arrival in Korea, at a monthly fee of 36,575 won.

- SK Telecom requires a Residence Card for foreign nationals seeking postpaid lines, and LG Uplus demands extra documents plus in person verification.

- Burner phones under foreign names jumped from 474 cases in 2019 to more than 71,000 in 2024, according to police data.

- Police uncovered a fraud ring using more than 11,000 ghost SIMs registered with foreign passport copies, tied to voice phishing, drug operations, and illegal lending.

- New national measures include biometric checks for SIM registration, a one line limit per foreign passport, and accountability for carriers that enable repeated illegal activations.

- Lawmaker Choi Hyung-du wants telecom verification linked to immigration databases and stricter oversight of high volume outlets.

- Technical steps, including liveness detection, ePassport chip validation, and real time checks against official records, can sharply reduce identity fraud.

- Policies can protect newcomers’ access by offering limited prearrival plans that unlock fully only after in person checks or Residence Card validation.