An ancient love poem returns to view

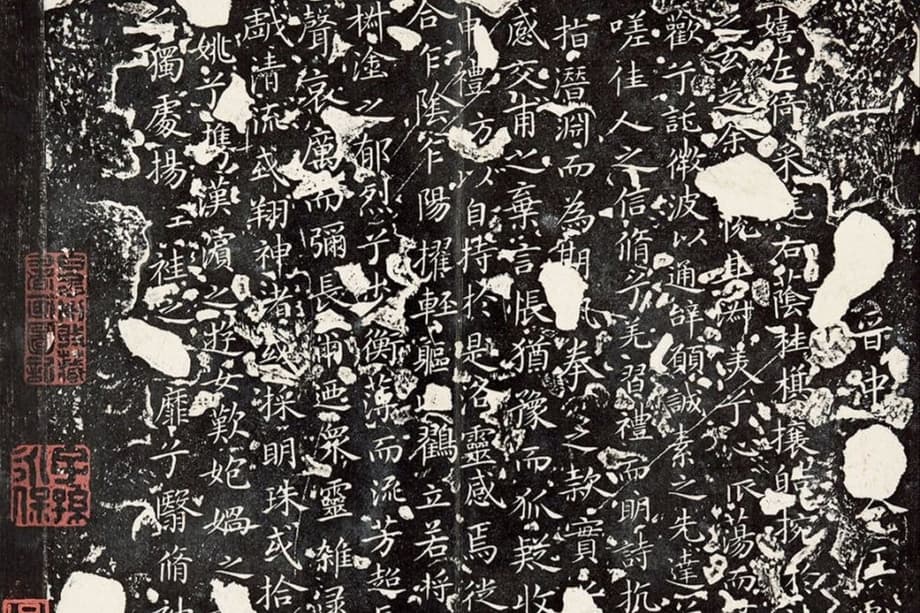

A Chinese research team has digitally reconstructed a 1,600 year old calligraphic treasure using artificial intelligence (AI). Peking University’s Centre for Chinese Font Design and Research announced that it completed a full scroll rendition of Rhapsody on the Luo River Goddess, known as Luoshen Fu, originally penned in the fourth century by master calligrapher Wang Xianzhi. Only fragments of the work survived. The team used a blend of calligraphic font design and AI character creation to recover the missing parts while preserving the artist’s style. The result is a continuous scroll of 919 characters based on about 250 authentic characters that remain.

Researchers analyzed the surviving glyphs, measured stroke weight, brush rhythm, character structure, and spacing. The model learned how Wang Xianzhi curved and pressed his brush, how he balanced dense ink with open space, and how he linked characters in running script. With those stylistic rules, the system generated the absent characters and arranged the poem as a complete scroll. The output is not a physical repair. It is a digital reconstruction that lets readers experience the poem in a form that mirrors the original hand.

Luoshen Fu is a prose poem by Cao Zhi, a prince of the state of Cao Wei during the Three Kingdoms period. He wrote it around AD 222. The text describes an encounter with the goddess of the Luo River, and it has inspired painters and calligraphers for centuries. Wang Xianzhi’s rendition, created in the Eastern Jin era, became famous for its graceful movement and expressive ink. The new digital scroll brings that flowing hand back into view for modern audiences.

What exactly was restored

Wang Xianzhi, son of the legendary Wang Xizhi, is counted among the greatest figures of Chinese calligraphy. He lived in the fourth century during the Eastern Jin. Together, father and son are known as the Two Wangs. They refined the running script and cursive script, emphasizing fluid motion and subtle control. Many of their works survive only in copies and rubbings, and gaps in the historical record have left key pieces incomplete.

For Luoshen Fu, roughly a quarter of the calligraphy was still legible across dispersed fragments. That gave the Peking University team about 250 characters to study in depth. The completed poem has 919 characters. The researchers built a generative model that could write the missing characters in Wang Xianzhi’s style and arrange them in a scroll consistent with the surviving parts. The project does not claim to recover lost ink. It presents a faithful stylistic continuation of the fragments so that the poem reads as a cohesive work again.

Who were Wang Xianzhi and Cao Zhi

Wang Xianzhi (AD 344 to 386) served as an official and gained fame as an artist in his own right. His calligraphy is admired for elegant rhythm and an innovative approach to structure. He experimented with the linking of strokes and with the placement of characters to create a dynamic sense of flow. Later dynasties studied his work and treated it as a standard of taste.

Cao Zhi (AD 192 to 232) was a prince and a celebrated poet of the Cao Wei court. He wrote Luoshen Fu after a journey near the Luo River. The poem blends courtly romance with spiritual longing, describing a vision of the river goddess as an ideal of beauty and virtue. Later artists interpreted the poem in painting and calligraphy, and versions of Luoshen Fu became a touchstone of literati culture.

How AI rebuilt the calligraphy style

Digital restoration of calligraphy differs from optical enhancement. The Peking University team did not simply brighten faded ink. Their aim was to model the artist’s style and then write new characters that fit that style. To do this, researchers performed a detailed analysis of the 250 surviving characters, capturing fine features like stroke direction, pressure changes, curvature, and the relative size of radicals within each character.

With those features in hand, the team trained a character generation system that acts like a calligrapher who has studied with Wang Xianzhi. The model learns how strokes begin and end, how lines taper, and how characters sit in the square. It then produces candidates for missing characters. Experts review the results, refine parameters, and select the versions that best match the original hand. This human in the loop process helps prevent mechanical repetition and guards against stylistic drift.

The final product is a continuous digital scroll where every generated character relates back to the authentic fragments. Spacing and rhythm match the surviving lines, and the layout keeps the sense of movement that defines the original. Readers get a full view of the poem while still knowing which parts are original and which parts are reconstructed.

In its public statement, Peking University framed the work as a cultural experiment that joins traditional art and new tools.

Peking University wrote: “This endeavour vividly illuminates the fusion potential of AI plus culture, where traditional calligraphic art gains fresh modes of expression in the digital age.”

A global shift in restoring ancient texts

The approach aligns with a broader wave of AI assisted work across the humanities. Deep neural networks have helped scholars restore damaged texts, attribute inscriptions to their place of origin, and estimate dates. The Ithaca system, trained on ancient Greek inscriptions, shows how AI can partner with experts. The model alone restores damaged text with an accuracy around 62 percent. When historians use it as a guide, their accuracy rises from about 25 percent to roughly 72 percent. The system also suggests likely places and time windows for the original inscriptions, giving researchers a stronger starting point.

Google DeepMind’s Aeneas extends that idea to Latin inscriptions. It integrates text and images, retrieves parallels across vast corpora, and proposes reconstructions for longer gaps. In tests with historians, Aeneas improved restoration and attribution tasks and proved useful in most cases. Projects like these keep experts in control. The software generates hypotheses, and people weigh context, style, and material evidence before accepting any change.

Work on the carbonized Herculaneum scrolls offers another angle. Researchers apply advanced imaging and machine learning to detect faint letters inside rolls of papyrus sealed since AD 79. This combination of non invasive scanning and AI driven text detection yields readings without unraveling the fragile originals. Careful validation and open methods help maintain trust.

China’s broader experiments with AI heritage

Chinese universities and cultural institutions are testing AI on paintings and murals as well. Researchers at Zhejiang University, led by art and archaeology scholar Tang Tan, devised a cross modal deep learning model that links poems and paintings. By learning how classical poetry describes landscapes and colors, the system proposes color palettes that match the intent of lost pigments. The team demonstrated fast, reversible recoloring on works such as Dong Yuan’s Residents on the Outskirts of Dragon Abode, giving conservators a way to preview and debate options before any physical action is taken.

At the Yongle Palace in Shanxi, a collaboration launched in 2019 used AI tools to revive the faded colors of Chaoyuan Tu, an enormous Yuan dynasty mural. The painting stretches nearly one hundred meters and portrays a gathering of Taoist figures in layered procession. Digital enhancement lets visitors see the grandeur of the composition with a clarity closer to its original impact while avoiding direct intervention on the wall.

Film studios are also turning to AI to refresh cultural memory. Under the Kung Fu Movie Heritage Project, companies plan to digitally restore one hundred classic martial arts films, from Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan staples to later hits. The project promises cleaner visuals and sound without rewriting stories. It has also inspired a fully animated reinterpretation of A Better Tomorrow built with AI tools across the production pipeline.

Tian Ming, chair of Canxing Media and a leader in the initiative, described the balance between machines and creators.

“AI is the brush, but creativity is the soul,” Tian said. “Classic kung fu films embody China’s spiritual backbone.”

What counts as authentic when AI fills the gaps

Restoration is never value free. A digital reconstruction of calligraphy is a reading of style, not a recovery of ink. Viewers should be able to distinguish original from generated characters and to learn how choices were made. Clear labeling protects both the artwork and the public, and it builds confidence in the result.

Technical safeguards help. Generative models can drift toward neat symmetry or repetitive shapes that a human master would avoid. Limiting training to authentic fragments, enforcing stroke order rules, and comparing against verified exemplars reduce those risks. Cross checks by calligraphers, historians, and conservators add judgment that software cannot supply.

Practical steps for responsible digital restoration

- Always mark reconstructions and list the team, the date, and the tools used.

- Publish side by side views of fragments, proposed completions, and full scrolls.

- Embed metadata and visual watermarks that identify generated characters.

- Invite independent review by external experts and keep an audit trail of revisions.

- Share data and code where possible so that other teams can test and improve methods.

- Release multiple versions when historical uncertainty remains, rather than one fixed reading.

- Clarify rights and licensing so that educational use and research are encouraged.

Why Luoshen Fu still matters

The allure of Luoshen Fu lies in the union of text and hand. Chinese calligraphy treats the written word as an art of gesture, where breath, wrist, and ink leave a record of the mind. Wang Xianzhi’s interpretation of Cao Zhi’s poem carries both literary elegance and personal feeling. A digital scroll that respects those qualities can widen access without flattening meaning.

Schools and museums can now present the poem in full, explain which characters have survived, and demonstrate how experts infer the rest. Interactive displays can zoom from the sweep of the scroll to the thickness of a single stroke. Readers encounter a complete narrative of longing and grace, while also learning how modern tools engage with fragile heritage.

Care that values accuracy and transparency will keep projects like this grounded. When teams document their process, invite critique, and update their results, digital restorations become part of the scholarly record. That makes the new Luoshen Fu both a tribute to Wang Xianzhi and a living resource for future study.

The Essentials

- Peking University used AI to create a complete digital scroll of Wang Xianzhi’s Luoshen Fu from about 250 surviving characters.

- The reconstructed work totals 919 characters and presents the poem as a cohesive scroll for modern readers.

- The project blends calligraphic font design with AI character generation, guided by expert review.

- Similar AI tools, such as Ithaca and Aeneas, help historians restore and date ancient inscriptions by pairing algorithms with human judgment.

- Chinese teams also apply AI to color restoration of paintings and to the digital remastering of classic kung fu films.

- Clear labels, watermarks, open methods, and independent review help maintain trust in digital reconstructions.

- The renewed Luoshen Fu showcases how technology can widen access while respecting the spirit of traditional calligraphy.