Why Manila Matters in a Taiwan Crisis

The Philippines has moved from the margins of Asia security to its center, not because Manila seeks a starring role but because geography and alliances leave little choice. The United States is the only country that maintains a deep unofficial relationship with Taiwan, yet anxiety over a potential Chinese move against the island is shared across the Indo Pacific and into Europe. Many governments want to deter conflict without formal commitments on Taiwan. Building stronger access, training, and legal frameworks in the Philippines has become their preferred way to shape the outcome of any crisis to the north.

- Why Manila Matters in a Taiwan Crisis

- Geography puts the Philippines at the heart of any Taiwan fight

- A fast growing network of alliances and legal frameworks

- Quiet but real coordination with Taiwan

- The new Philippine defense playbook, from coastal missiles to unmanned fleets

- Managing escalation while building deterrence

- Humanitarian and economic planning for a crisis spillover

- What Chinese planners could do, and how Manila aims to counter them

- What to watch next

- Key Points

Two developments show how quickly this is unfolding. Australia and the Philippines plan to finalize a new defense agreement in 2026 that will make regular defense meetings routine, expand joint exercises, and support Australian investment in Philippine defense infrastructure. Japan’s Reciprocal Access Agreement with the Philippines is now in force, allowing their forces to train on each other’s territory, grow industrial cooperation, and exchange technology. These initiatives reinforce the U.S. Philippines Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement, which gives the United States rotational access to Philippine locations, many of them in northern Luzon within reach of the Luzon Strait. A cluster of new arrangements with Canada, New Zealand, France, South Korea, the United Kingdom, Italy, Ukraine, Germany, and Lithuania deepens the trend. Lithuania’s defense minister has even spoken openly about Chinese pressure on Taiwan and the Philippines, a measure of how far concern has spread.

What draws this diverse coalition to the Philippines is not only proximity to Taiwan. It is the ability to create practical deterrence that can be used short of war. Upgrades to northern island airstrips and ports, combined exercises that rehearse coastal defense and sea control, and legal permissions for rapid deployments give partners stubborn leverage if tensions spike. Manila’s agenda is also shifting. The government is modernizing its forces, positioning units in the north, and embracing new concepts that are designed to complicate any Chinese plan in the South China Sea and across the Bashi Channel. The Philippines has become the southern anchor of any strategy to keep Taiwan from being isolated and to keep the western Pacific open.

Geography puts the Philippines at the heart of any Taiwan fight

The map explains Manila’s new importance. Taiwan sits in the middle of the first island chain, the natural arc that runs from Japan through Taiwan to the Philippines. The Luzon Strait between Taiwan and the Philippines is the main southern exit from the Chinese coast into the Pacific. Within that strait, the Bashi Channel is the critical passage. Its deep waters are suited to submarine operations. In a Taiwan contingency, Chinese ships and submarines would try to break out to the Pacific through Bashi. Allied forces would try to monitor and, if needed, limit that movement. The Philippines’ northernmost island, Mavulis, lies only a short distance from Taiwan’s Orchid Island, directly overlooking the channel.

What is the Luzon Strait and why it matters

Analysts describe the Bashi Channel as the likely hinge of any maritime battle over Taiwan. A blockade of the island would require sustained naval and air presence. Submarines transiting from the South China Sea into the Philippine Sea would depend on Bashi’s depth and concealment. That is why Manila’s small outpost on Mavulis matters. A Philippine Navy detachment was established on the island in 2023. Building a forward operating site with sensors, communications nodes, and resilient logistics could amplify the country’s maritime domain awareness. Networked with allied systems, those sensors would expose movements through the channel and complicate Chinese planning.

The broader stakes are economic as well as military. Japan depends heavily on cargo that transits the Taiwan Strait, and the Luzon Strait is a key alternative route when shipping patterns shift. If China controlled Taiwan, the Philippines would be bracketed by Chinese dominated waters to the north and west, putting more pressure on Manila’s own trade and freedom of maneuver. Controlling or contesting the Luzon Strait would shape whether regional sea lanes remain open. That reality makes the Philippines central to plans that aim to keep deterrence credible and escalation controllable.

A fast growing network of alliances and legal frameworks

The Philippines is becoming a hub for combined defense. The U.S. Philippines Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement gives the United States rotational access to nine locations, including several in northern Luzon close to Taiwan. This does not create permanent bases, but it does allow prepositioning of equipment, rapid construction of facilities, and frequent training. Australia’s planned defense agreement with the Philippines in 2026 will institutionalize regular consultations, expand exercises, and channel investment into Philippine infrastructure. Exercise Alon already put more Australian forces on Philippine terrain for advanced combined training. Japan’s Reciprocal Access Agreement enables both countries to train and operate on each other’s soil and to grow industrial and technology ties. The result is a set of legal tools that turn geography into practical access across multiple partners.

How EDCA and joint exercises change the map

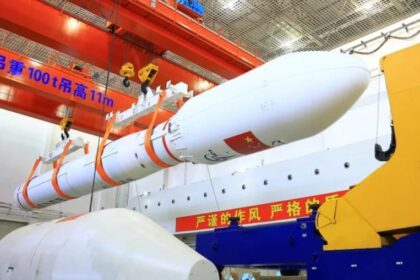

These agreements are not just signatures. They change the distribution of military capability in and around the Luzon Strait. In early 2024, the United States demonstrated a new land based, road mobile missile system in Luzon during Exercise Salaknib. The Typhon system can launch Tomahawk and SM 6 missiles. Its presence signaled that distant targets at sea and ashore can be held at risk from Philippine soil if a crisis demands it. Marine forces have also practiced deploying Naval Strike Missile systems to the Luzon Strait during Balikatan, which is now a large trilateral training venue with Japan joining key phases. The U.S. approach to Agile Combat Employment, which disperses aircraft and support across smaller airfields, fits naturally with access to Philippine sites. It forces Chinese planners to calculate against more locations, not just a few major bases. Manila is also discussing additional arrangements with European and Indo Pacific partners, which would give like minded militaries more places to train and more options to respond.

Quiet but real coordination with Taiwan

Manila observes the One China policy. Even so, unofficial coordination with Taiwan has expanded. Senior security officials from both sides have met out of uniform. Taiwanese officers observed this year’s Balikatan drills that brought U.S., Philippine, and Japanese forces together. On the ground, the Philippines is reinforcing its northern islands with improved airstrips and seaports, and it has run evacuation scenarios for Philippine citizens in Taiwan should a crisis erupt. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has said the country would inevitably be involved in any cross strait conflict because of proximity. Manila’s defense treaty with the United States and the U.S. Taiwan Relations Act also shape expectations about how help might be requested and delivered.

Signals from the armed forces and local units

The military picture in northern Luzon has shifted. The Philippines relocated a veteran marine brigade to Ilocos Norte and placed marine units within reach of the strait. Their training now emphasizes ambush tactics, denial of landing sites, dispersion into caves, and rapid counter mobility using civilian trucks adapted for military use. Reservists are being integrated into coastal defense. The unit’s banners in Camp Cape Bojeador include a stark promise tied to the latitude of the country’s northern territories: none shall cross the 18th parallel unscathed. The message reflects a wider posture that treats the north as a forward line of defense. Japanese and U.S. drills nearby mirror that focus.

Renato Cruz De Castro, a professor of international relations at De La Salle University, said Philippine planners are thinking about the risk that Chinese forces might try to secure the country’s northern flank in a Taiwan scenario.

I’m assuming that in a Taiwan contingency scenario the Armed Forces of the Philippines are looking at the possibility of a Chinese attack on Northern Luzon.

That assessment helps explain why Manila is trying to both thicken its northern defenses and grow the legal frameworks that allow allied forces to train there more often. It is an indirect way to enlarge the costs of any Chinese operation that crosses the Bashi Channel.

The new Philippine defense playbook, from coastal missiles to unmanned fleets

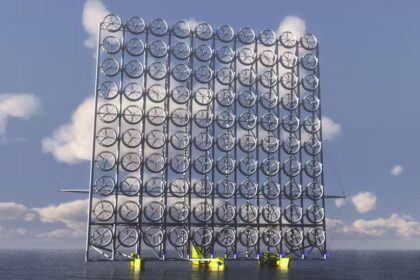

Manila’s modernization plan is not a race to buy large capital ships. The preferred approach is a porcupine defense built on smaller, cheaper, and distributed systems that punish any aggressor. Maritime autonomous systems are central to this shift. Uncrewed surface vessels and small drones can swarm, scout, relay targeting data, and even carry weapons. A network of these assets extends awareness across an archipelago without telegraphing a single point of failure. Instead of a linear kill chain that can be broken with a single strike, the network functions as a kill web, where many nodes can sense, decide, and strike. Losing one platform does not collapse the whole system.

From coastal missiles to unmanned swarms

The mesh fleet concept takes this further. Families of uncrewed boats, such as MARTAC’s MANTAS and Devil Ray lines, can deploy rapidly from beaches and small harbors and operate as a coordinated group. Attritable systems like the M18 Muskie can be sent on one way missions. Manned and uncrewed platforms working together generate distributed maritime effects that can complicate an adversary’s plan at many points. Land based missiles round out the picture. The Philippines has received India’s BrahMos supersonic missiles and has trained alongside U.S. units operating Naval Strike Missiles in the strait. Combined with better maritime domain awareness and coastal radar, these assets create angles of attack that a larger navy cannot easily ignore. They are also faster to field. A 3 to 5 year program of acquiring mesh fleet platforms and sensors is far more attainable than a decades long acquisition of large warships. The United States and partners are investing in infrastructure and training to help the Philippines stand up these capabilities at speed.

For Manila, this is about more than technology. The porcupine concept changes the cost calculus. Uncrewed vessels are relatively cheap, persistent, and expendable. That makes it expensive for an adversary to suppress them. If combined with dispersed marines, mobile coastal missiles, and rapid logistics, the Philippines can present a denial problem across a wide area that includes the Luzon Strait and approaches to northern Luzon. Even a modest force can create significant risk for much larger fleets.

Managing escalation while building deterrence

Growing cooperation also brings choices about how to avoid unintended escalation. Recent confrontations in the West Philippine Sea have included collisions and water cannon blasts. Manila’s leaders have tried to hold firm at sea while keeping diplomatic channels open. Some strategists argue that the United States should keep the focus on helping the Philippines improve coast guard and naval capacity, avoid expanding access sites too quickly, and let Manila lead around disputed features. The aim is to strengthen defense and crisis management without pushing the contest into a spiral of military moves and countermoves that neither side controls.

Former national security adviser Hermogenes Esperon Jr. has argued that Philippine security rests on more than ships and missiles. He has described the need to sustain public trust and mobilize society in a careful, measured posture.

Security should not live solely in the domain of generals or diplomats. It must be embedded in the fabric of our societies.

National Security Adviser Eduardo Año has warned that China’s challenge extends into cyberspace and domestic vulnerabilities. He urged a coordinated response that draws in government, allies, and the private sector.

Asymmetric threats demand symmetric unity and systematic actions.

A strategy that mixes credible denial with assertive restraint lowers the odds of miscalculation while preserving the ability to act if coercion crosses the line.

Humanitarian and economic planning for a crisis spillover

Any conflict over Taiwan would test the Philippines in ways that reach beyond the military domain. Manila would need to support and, if necessary, evacuate its citizens working in Taiwan. The northern provinces and Batanes could become the first safe harbor for refugees. That requires logistics planning, medical support, and resilient infrastructure in places that are remote even in peacetime. The government has already run evacuation scenarios in recent exercises.

Trade routes are part of the calculus. If tensions rise, shipping may detour away from the Taiwan Strait, sending vessels south of the Philippines and back up through wider gaps like the Miyako Strait near Japan. A single detour can add roughly a thousand miles to a voyage, raising costs and stretching supply chains. For Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines, keeping the straits open and predictable is more than a military issue. It is an economic lifeline.

What Chinese planners could do, and how Manila aims to counter them

China uses gray zone tactics to press its maritime claims, from close approaches by coast guard ships to swarming fishing vessels. In a Taiwan crisis, Chinese planners might try to preempt threats from the north by striking or intimidating key terrain in the Philippines, just as Japan did to U.S. positions in the early days of the Pacific War. Allied planners anticipate this risk. That is why fixed defenses on key islands, deep magazines, and reinforced positions are receiving attention from Tokyo to Manila. Undersea sensors, submarines, uncrewed underwater vehicles, anti ship missiles, and mines can combine to slow Chinese naval mobility through chokepoints. Ground units at critical locations free up mobile units to respond where needed. For the Philippines, forward sites in Batanes and northern Luzon, fast boat bases, and mobile coastal missiles are the ingredients of a dispersed defense that is hard to predict and harder to suppress.

What to watch next

Several signposts will show how far Manila’s central role will grow. Australia and the Philippines expect to finalize their defense agreement in 2026. The Japan Philippines Reciprocal Access Agreement will move from signature to habit as units train on each other’s ground. U.S. access to EDCA sites will continue to expand, especially in the north. Exercises will rehearse deployments of Naval Strike Missile batteries and dispersed air operations in the Luzon Strait. The Philippines will keep building out northern infrastructure, including Mavulis and other Batanes locations. Expect more experimentation with uncrewed surface vessels and drone swarms at sea, combined with coastal radar and maritime patrol aircraft overhead. Manila is also weighing new agreements with European partners and the United Kingdom that would allow more visits and training. At the same time, cyber defense and crisis communications will take a larger place in Manila’s planning as Chinese linked malware and intrusions probe for weaknesses. Through it all, Manila will try to signal that its buildup is defensive and that cooperation is about keeping sea lanes open, not provoking a fight.

Key Points

- The Philippines has become the southern anchor of coalition planning for a Taiwan crisis, driven by geography and new access agreements.

- Australia and the Philippines aim to finalize a defense pact in 2026, while Japan’s Reciprocal Access Agreement with Manila is already in force.

- U.S. access under EDCA includes northern Luzon sites near the Luzon Strait, with joint drills practicing missile and coastal defense operations.

- Unofficial coordination with Taiwan is growing, including Taiwanese observers at Balikatan and quiet exchanges among security officials.

- Philippine forces in northern Luzon now train for ambushes, denial of landing sites, and dispersion, with reservists integrated into coastal defense.

- Manila is embracing a porcupine strategy that uses uncrewed vessels, drones, and land based missiles to create a resilient, distributed defense.

- Mavulis Island and the Bashi Channel are key chokepoints, and a Philippine Navy detachment on Mavulis strengthens monitoring of the channel.

- Deterrence is paired with restraint, as leaders stress diplomacy, crisis management, and cyber defense to avoid escalation.

- Humanitarian and economic planning is advancing for potential refugee flows and shipping detours if tensions spike around Taiwan.

- Watch for more frequent deployments of Naval Strike Missiles, expanded EDCA site activity, and increased use of autonomous maritime systems around the Luzon Strait.