A high stakes LNG handover off Malaysia

Satellite images captured a rare liquefied natural gas transfer at sea involving a cargo from a United States sanctioned Russian export plant, staged off the coast of Malaysia. The operation showcased how Russia’s shadow fleet, a web of vessels with opaque ownership and irregular tracking behavior, continues to move energy under pressure from Western restrictions. The LNG carrier Perle, which came under US sanctions earlier in 2025, was seen aligned in parallel with another gas carrier about 90 kilometers east of peninsular Malaysia, the classic setup for a ship to ship transfer of cargo at sea.

- A high stakes LNG handover off Malaysia

- Why this transfer stands out

- The ships, the cargo, and the long detour

- Inside the shadow fleet playbook

- Malaysia’s response and the limits of enforcement

- Sanctions pressure tightens on Russian energy flows

- Who might buy this gas and why

- Risks of LNG transfers in tropical open water

- What to Know

Images from Europe’s Sentinel 2 satellite on October 18, supported by ship tracking data gathered earlier in the voyage, show the two vessels side by side. The geometry and spacing are consistent with a live transfer. While this stretch of sea near Southeast Asia is a known arena for open water transfers of sanctioned crude oil, executing the same maneuver with LNG is unusual and technically demanding. Analysts say this appears to be the first documented attempt to hand over a Russian LNG cargo in waters off Malaysia.

The Perle stopped transmitting its position data, a hallmark of dark activity that complicates monitoring. Satellite and registry clues point to an older Chinese managed LNG carrier as the receiving ship, identified by several tracking specialists as CCH Gas, though the vessel’s signals were spoofed and authorities have not issued an official confirmation. The location, timing, and parallel drift pattern indicate a transfer window carefully chosen to avoid detection near busy anchorages and closer patrols.

Why this transfer stands out

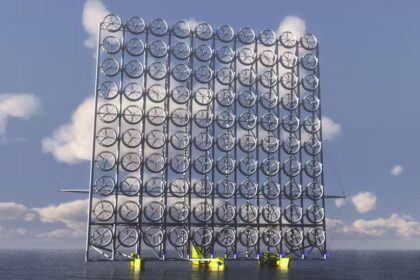

Open water transfers of LNG demand precision and controlled conditions. Oil can be moved at sea with robust hoses and established procedures developed over decades. LNG is different. The cargo is supercooled methane kept at around minus 162 degrees Celsius. The equipment, choreography, and safety tolerances are more complex, which is why most LNG handovers occur at terminals or in sheltered waters where motion can be managed and emergency support is nearby.

What makes LNG transfers more complex

Two large LNG carriers must moor securely alongside one another using heavy fenders and multiple mooring lines. Crews connect cryogenic transfer lines and verify an emergency shutdown link between ships. Lines and manifolds are purged with inert gas before and after flow. Transfer rates are tuned to sea state and vessel motion to avoid undue stress on hoses and connections. Operations depend on low wind and swell so that relative movement stays within tight limits. A small error can trigger an automatic trip of the emergency system and a rapid halt in flow.

The risks include cold burns to steel if liquid leaks, brittle fracture in unprotected materials, and formation of a methane vapor cloud that must disperse safely in the open air. Ignition sources are strictly controlled. Crew training and exacting procedures are essential, which is why companies typically plan LNG transfers at protected anchorages rather than exposed stretches of sea.

Why operators pick Southeast Asia

The region sits at a strategic maritime crossroads where dozens of tankers converge en route to China and other Asian markets. A ship to ship handover offshore can repackage the cargo on a vessel that is not on a sanctions list, reducing the paper trail that might link a buyer to a blacklisted ship. Enforcement in crowded international waters is complicated. Authorities focus on national anchorages and territorial seas where they can board quickly. The move to a point roughly 90 kilometers from the coast reduces the chance of immediate disruption, yet remains close to major trade routes and potential buyers.

The ships, the cargo, and the long detour

Data compiled by maritime analytics firms indicate the Perle loaded LNG at Gazprom’s Portovaya facility on Russia’s Baltic coast in February 2025. Then it waited for months with no clear destination, a common pattern as Russian sellers struggle to place sanctioned cargoes. In July, the vessel rounded the Cape of Good Hope and headed toward Asia. Portovaya exports to foreign buyers largely halted after the United States sanctioned the plant in January, making this voyage one of the first eastbound runs for the site’s output in many months.

The likely counterpart in the transfer is the 145,000 cubic meter LNG carrier now named CCH Gas. Built in 2006 and previously sailing as Condor LNG, the ship was sold in early 2025 to a Hong Kong based firm and is reported to be managed from Shanghai. Tracking specialists noted that both the Perle and the second ship used periods of signal silence or spoofing, tactics designed to confuse any back tracing of the cargo’s path and ownership.

The Perle’s technical and commercial management has been linked to Dreamer Shipmanagement LLC FZ. The company’s registered address is the Meydan hotel in Dubai, a location that appears in the corporate paperwork of several entities connected with the growing shadow fleet that carries sanctioned Russian energy. Public databases do not list a working email or phone for the manager, which is common in this part of the trade’s gray ecosystem.

Inside the shadow fleet playbook

Dark ships operate with layers of secrecy. They often use shell companies in permissive jurisdictions, swap flags and names with little notice, and switch off the automatic identification system, or AIS, which is intended to broadcast identity and position for safety and navigation. Some ships broadcast false positions, a tactic known as spoofing, to appear far from actual operations. Ship to ship transfers outside ports create breaks in the chain of custody that make it harder to link the cargo back to sanctioned producers.

Even with AIS dark periods, satellites pick up telltale signs. Optical imagery and synthetic aperture radar can spot two large carriers drifting in parallel with fenders deployed. Analysts cross reference those moments with earlier tracks, registry clues, and crew or ownership changes to piece together the story of a cargo, as happened in the case off Malaysia.

A research report on maritime security warned about the growing risks created by these opaque trades, which often rely on older vessels with uncertain maintenance and insurance coverage. The analysis highlighted not just geopolitical concerns, but practical worries for coastal states and shipping lanes.

“The shadow fleet undermines established maritime insurance and compensation systems, leaving coastal states vulnerable to the financial and environmental costs of accidents.”

When a casualty occurs during a transfer far from regulated facilities, costs fall on coastal responders and, sometimes, on victims with little recourse to a reliable insurer. The move into LNG makes those stakes higher because response options differ from oil spills and require specialized gear and expertise.

Malaysia’s response and the limits of enforcement

Malaysian authorities have tightened control over ship to ship activity within national waters. Officials announced the closure of the East Outer Port Limits anchorage off the southern coast and warned that any vessel caught conducting unauthorized transfers inside Malaysian waters would face detention. The aim is to stop ships from using designated anchorages as informal hubs for sanctioned cargoes that present safety and reputational risks.

The rendezvous point east of the peninsula sits roughly 90 kilometers offshore. That is well outside the 12 nautical mile territorial sea, where port state control powers are strongest, though still inside Malaysia’s exclusive economic zone. In that zone, a coastal state has rights over resources and environmental protection, but day to day policing of foreign commercial shipping is less straightforward. The shift offshore suggests operators are adapting to stay just beyond the reach of new checks while remaining close to preferred routes toward Chinese ports.

Malaysia has boarded and detained tankers suspected of improper transfers near busy anchorages in the past year. Moving LNG handovers farther offshore complicates rapid intervention, and it forces authorities to lean on satellite monitoring and coordination with partners to spot and stop hazardous activity in time.

Sanctions pressure tightens on Russian energy flows

Western pressure on Russian energy has intensified through 2025. The United States sanctioned the Portovaya LNG plant early this year and flagged deceptive shipping practices such as AIS disablement by vessels servicing sanctioned projects. Another blacklisted project, Arctic LNG 2, has nonetheless managed to move cargoes to China since late August, signaling Moscow’s determination to keep exports rolling despite new hurdles.

European policymakers have also broadened measures. The latest package adds more than one hundred additional tankers believed to be tied to Russia’s shadow fleet to the sanctions list and, for the first time, targets a ship registry that enabled reflagging by opaque owners. The framework tightens price cap enforcement and expands financial restrictions on entities linked to energy revenues. The United Kingdom’s sanction of a Chinese LNG terminal that handled Arctic LNG 2 cargoes reflects a wider effort to make such trades harder to complete.

Senior officials framed the effort as a message of resolve. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen underscored the stance in remarks on sanction enforcement and Russian aggression.

“Strength is the only language Russia will understand.”

Even with stronger measures, Russian LNG continues to reach buyers in Europe and Asia through legacy contracts and intermediaries. Legislators are weighing additional steps, such as curbs on transshipments and stricter insurance documentation, in a bid to close loopholes while avoiding new shocks to energy security.

Who might buy this gas and why

China remains the most likely destination for the Perle’s cargo. Recent patterns in crude and LNG illustrate a route that keeps paperwork clean for end buyers. Cargoes move via ship to ship transfer onto a vessel that is not under sanctions, then proceed to a terminal operated by a private company. Some state owned port groups in China have discouraged calls by ships designated by the United States, which has nudged sanctioned flows toward privately managed berths that face fewer constraints from public guidance.

At the same time, Chinese buyers face a changed LNG market. A 15 percent tariff on LNG imported from the United States took effect in February 2025, and Chinese companies have increased the resale of contracted US cargoes to Europe. Discounted Russian shipments, especially if reloaded onto a carrier with no designations on record, can look attractive in this setting, even if route and handling costs are higher than standard trades.

Ship to ship transfers also disrupt visibility. A buyer who wants to avoid any direct link to a sanctioned ship can take delivery from a carrier without designations, even when the molecules originated in Russia. That does not erase sanction risk, but it creates distance that traders believe reduces the chance of being caught in secondary measures. The offshore LNG handover off Malaysia fits that pattern.

Risks of LNG transfers in tropical open water

LNG presents different hazards from oil. If liquid escapes, it flashes into extremely cold vapor that hugs the surface before dispersing. Transfer systems are designed with multiple layers of protection. An emergency shutdown signal between ships triggers valves to close in milliseconds, and emergency release couplings can separate under tension to prevent catastrophic hose failure. Those protections assume equipment is maintained, testing is up to date, and crews rehearse the procedures.

Conditions east of peninsular Malaysia can change quickly. Seasonal monsoon winds drive squalls and cross currents that challenge side by side mooring. Even a minor contact can damage manifolds or cryogenic hoses. The area is one of the busiest shipping corridors in the world. The presence of large gas carriers engaged in delicate transfer work raises collision risk if other ships do not keep clear.

Many vessels in the shadow trade are older units with opaque insurance coverage. If an incident occurs outside a regulated terminal, first responders may be far away, and cost recovery can be difficult if the owner of record is a shell company. The combination of technical complexity, busy sea lanes, and limited oversight makes open water LNG transfers a risky proposition for coastal states and crews alike.

What to Know

- Satellite imagery on October 18 showed the sanctioned LNG carrier Perle aligned alongside another ship about 90 kilometers east of Malaysia, consistent with a ship to ship transfer.

- Analysts believe this is the first documented transfer of Russian LNG off Malaysia.

- The Perle loaded at Russia’s Portovaya plant in February 2025, idled for months, then sailed around the Cape of Good Hope toward Asia.

- The receiving ship is suspected to be the Chinese managed CCH Gas, but identity has not been confirmed by authorities.

- Perle is linked to Dreamer Shipmanagement LLC FZ, which registers at a Dubai hotel address used by firms in the shadow shipping trade.

- Malaysia closed a key anchorage to curb illegal transfers and says unauthorized ship to ship operations in national waters will lead to detention.

- The United States and European Union expanded sanctions on Russian energy and the shadow fleet, and the United Kingdom targeted a Chinese LNG terminal tied to Arctic LNG 2 cargoes.

- China remains the most likely buyer, with some private terminals receiving cargoes moved off sanctioned ships via offshore transfers.

- LNG transfers at sea carry elevated safety and environmental risks, especially in busy, weather exposed waters.