Why China’s AI chip race matters now

China is racing to reduce its reliance on imported processors for artificial intelligence. The country is pouring investment into research labs, foundries and cloud infrastructure so that future breakthroughs in large language models, robotics and automation run on domestic silicon. The strategic goal is clear: produce high end chips at scale, build the software to use them well and keep critical computing capacity within national reach.

A jolt to that ambition arrived in 2024 when the start up DeepSeek unveiled a conversational AI that rivaled leading Western systems. The firm said it trained the model with far fewer premium accelerators than peers, a signal that smarter software and efficient training regimes can partially offset hardware limits. The launch briefly knocked Nvidia’s market value and put a spotlight on how quickly Chinese developers are moving. In the months since, tech giants and chip designers across China have announced plans to challenge Nvidia in data centers at home.

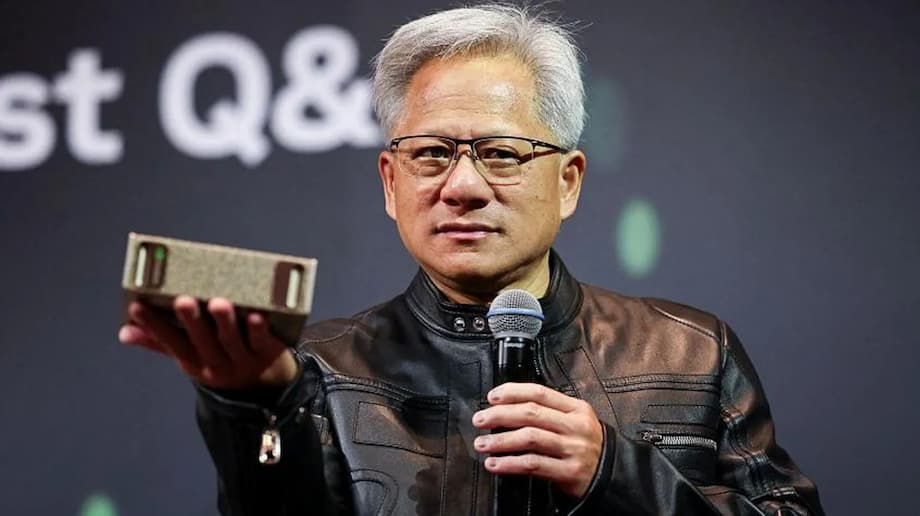

Nvidia’s chief executive Jensen Huang has credited China with a deep pool of engineering talent and relentless domestic competition. Speaking on a technology and business podcast in September, he praised the country’s momentum and issued a challenge to his own side.

“This is a vibrant entrepreneurial, high tech, modern industry,” he said. “We have to compete for our survival.”

How Chinese players plan to compete

Several Chinese firms are building alternatives to Nvidia’s accelerators and full stack systems. Huawei has rolled out new Ascend processors and a plan to support developers over three years. Alibaba says its latest accelerator can match the performance of Nvidia’s H20, a chip tailored for China under US rules, while using less energy. Start ups like MetaX and Cambricon are winning contracts with major enterprises. Large platforms, including Tencent and Baidu, are designing custom chips for their own clouds. The message to domestic customers is consistent: if export policy limits access to American hardware, Chinese options will fill the gap.

Huawei’s system level strategy

Huawei is leaning on system architecture to narrow the gap with Nvidia. At the World Artificial Intelligence Conference in Shanghai, the company showed CloudMatrix 384, an AI computing system that packs 384 Ascend 910C processors into a single deployment. Nvidia’s rival GB200 NVL72 uses 72 B200 chips, but Huawei’s design takes a different path. The CloudMatrix uses a supernode style connection fabric so hundreds of processors can act as one pool of compute, with very fast links among chips. By scaling horizontally, Huawei aims to offset weaker single chip performance with stronger system cohesion.

Industry analysts say that approach can deliver competitive results on specific workloads. Reports have suggested CloudMatrix outperforms Nvidia’s GB200 NVL72 on some metrics even though Huawei must rely on older manufacturing processes. The system is already live on Huawei’s cloud, giving Chinese customers an at home alternative for training and serving models. The architecture choice also matches China’s policy goal to build around export limits by finding gains at the system level.

Alibaba and a growing bench of challengers

Alibaba has announced a new AI accelerator that state media said equals the H20 while consuming less power. MetaX is supplying chips to China Unicom. Cambricon’s valuation has more than doubled in recent months as investors bet on rising domestic demand for accelerators. Tencent is developing in house chips for its cloud and AI services. These projects build on a larger shift among Chinese companies who are moving workloads to homegrown hardware when performance, availability and cost line up.

Developers are already adapting. Chen Cheng, general manager for AI translation at iFlytek, described how her team navigated recent restrictions on US hardware by switching to domestic processors.

“Now our model is trained on Huawei chips, currently the best in China,” she said.

What export controls and crackdowns are changing

Export rules have reshaped the market. Since 2022, Washington has imposed escalating limits on the sale of advanced AI chips to China. The latest moves shut the door on Nvidia’s H20, a processor designed to meet prior export thresholds. Lawmakers have advanced measures that would require US chipmakers to prioritize domestic customers over foreign buyers, even as companies warn that rigid rules could slow innovation and redirect demand. One recent policy would also send a portion of revenue from certain AI chip sales in China to the US government. Tighter controls mean American suppliers face a smaller addressable market in the country that purchases more chips than any other.

Beijing has responded with enforcement at the border and pressure at home. Authorities have instructed major tech firms to pause orders for Nvidia accelerators and stepped up inspections at ports to intercept unlicensed or misdeclared shipments, including China focused models like the H20 and RTX 6000D. Officials are probing smuggling networks that had brought high end processors into domestic data centers through indirect routes. Separately, regulators have opened an anti monopoly inquiry into Nvidia, signaling deeper scrutiny of its business practices inside China. These steps aim to push buyers toward local suppliers and to tighten the gray market pipeline.

Handel Jones, a long time semiconductor consultant, warned that the collective effect could be profound for American firms that have relied on Chinese demand.

“For the US semiconductor industry, China is gone,” he said.

Where performance still differs: benchmarks and software

Claims of parity deserve careful examination. Public data on Chinese accelerators is limited and standardized tests remain sparse. Performance depends on the task, the size of the model, interconnect bandwidth, memory architecture and the quality of the software stack that sits between the chip and the application. Researchers who have worked with both ecosystems say Chinese chips have closed the gap in predictive tasks, where a model completes a sentence or classifies an image, but still trail in complex analytics and large scale training.

Computer scientist Jawad Haj Yahya, who has tested American and Chinese accelerators, cautions that parity depends on workload.

“The gap is clear and it is surely shrinking. I do not think it is something they will catch up on in the short term,” he said.

That difference matters because training is the heavy lift in modern AI. It requires vast compute budgets, very fast links among processors and high bandwidth memory that can feed those processors without bottlenecks. Analyses indicate Huawei’s 910B is solid for inference, the phase where a trained model answers queries, but has limits in inter chip connectivity and memory speeds that make it less attractive for large training runs. Even Nvidia’s restricted H20 remains a preferred option for many users inside China when they can get it. Domestic developers say training can take weeks. DeepSeek’s widely discussed run took between three and eight weeks for a final stage, a costly effort by any measure even with efficient code.

Software is the other obstacle. Nvidia has spent years building a suite of tools, libraries and networking software that developers trust at scale. That stack bends workloads toward Nvidia hardware and shortens the path from prototype to production. Huawei is working to answer with its own framework and has promised to open more designs and code to domestic developers. Adoption is growing, yet retraining teams, rewriting code and revalidating models take time, which slows migration away from entrenched platforms.

Semiconductor engineer Raghavendra Anjanappa argues that China can meet many needs with local chips, but the hardest problems still favor US hardware.

“Realistically, China can reduce its dependence on American chips in less advanced tools, but does not have the raw performance of US chips to train more complex AI systems,” he said.

The manufacturing bottlenecks holding China back

A second set of constraints sits in the factory. US and Dutch controls restrict access to advanced lithography equipment used to produce the smallest transistors. That forces Chinese fabs to push older machines to their limits with repeated patterning, which is slower, more expensive and yields fewer good dies per wafer. Analysts tracking fabrication say yield rates for large AI processors in China have improved but remain well below the levels reached by global leaders. Reports this year describe a move from roughly 20 percent to 40 percent yield for a new Huawei chip, while leading fabs abroad can approach about 60 percent for devices of similar size. Lower yield raises cost and limits the number of working accelerators that reach the market.

Packaging and memory are just as hard. AI accelerators rely on high bandwidth memory to keep thousands of cores fed with data. The chips must be packaged with advanced techniques that stack and connect components while pulling heat away. Chinese teams can build these parts, yet shortages of top tier memory and limits on access to tooling constrain output. Functional issues remain. Prior reports noted that some domestic chips struggle with inter chip connectivity and memory speeds, which hold back training efficiency at scale.

None of these hurdles are insurmountable, but they take time, capital and a steady inflow of specialized equipment. Stephen Wu, a former AI engineer who now runs an investment firm, captured the strategic logic behind Beijing’s long push.

“China wants chips that policy cannot take away,” he said.

What it means for data centers and markets

Every data center operator weighs three priorities: performance, energy use and supply assurance. If a domestic accelerator delivers acceptable speed for a target workload at a lower power cost, a Chinese buyer gains a reason to switch. That case looks strongest today for inference and smaller model training where system level designs can offset weaker single chip performance. For frontier model training that pushes the limits of scale, Nvidia retains the lead in both silicon and software. The result is a split deployment pattern inside China, with the most demanding projects still seeking American chips whenever policy allows.

The policy picture raises new choices for global technology firms. Tighter US rules and Beijing’s customs enforcement are shrinking legal supply routes into China. Allegations of a gray market for refurbished or repurposed accelerators have prompted deeper checks at ports. Import frictions slow data center expansion timelines and push more workloads toward local suppliers. Meanwhile US legislators want to ensure American customers do not wait behind Chinese buyers for scarce parts, and new conditions on revenue from China add to the cost of doing business there.

Nvidia, for its part, is trying to walk a narrow line. The company has sought to meet regulations while serving Chinese customers with compliant products. During a visit with Chinese business leaders this year, Jensen Huang underscored that approach.

“We are going to continue to make significant effort to optimize our products that are compliant within the regulations and continue to serve China’s market,” he said.

Timeline and scenarios

How fast can China close the gap at the top end of AI compute. Analysts offer different timelines, but a common view is emerging. Many believe Chinese firms can reach broad self sufficiency for midrange and inference tasks within about five years, while matching the best American training platforms could take well beyond that. Some place a full match across processors, high bandwidth memory, advanced packaging, networking and software into the next decade.

Momentum on the ground is real. Huawei is increasing output, Alibaba is investing, and a growing cohort of designers from MetaX to Cambricon are winning buyers. Government support remains strong and domestic demand for AI services is surging. Even so, bottlenecks in tooling, yields and developer ecosystems will limit how quickly performance catches up at the very top of the market. The likely near term outcome is a more mature Chinese ecosystem that handles a large share of the country’s AI needs, with persistent dependence on foreign hardware for the largest training runs whenever policy permits access.

China’s state led approach is both a strength and a constraint. Central direction concentrates resources on clear targets, but it can also blunt risky ideas that lead to breakthroughs. Chia Lin Yang, a computing professor who studies chip design, cautioned that uniform goals can work against creativity while also noting the depth of available talent.

“It can make it harder for disruptive ideas to break the mould,” she said. “You cannot underestimate China’s ability to catch up.”

Key Points

- China is investing heavily to build high end AI chips at scale and reduce reliance on imports.

- DeepSeek’s 2024 model training showed efficiency gains that rely on smarter software, not just more chips.

- Huawei’s CloudMatrix 384 uses hundreds of Ascend 910C processors with a fast interconnect to compete at the system level.

- Alibaba, MetaX, Cambricon, Tencent and Baidu are pushing domestic accelerators and custom designs for local data centers.

- US restrictions now block Nvidia’s H20 and could require American chipmakers to prioritize domestic customers and share revenue from some China sales.

- China has tightened enforcement at ports, discouraged new Nvidia orders and opened an anti monopoly probe into the company.

- Experts say Chinese chips look competitive for inference but still lag in large model training and complex analytics.

- Manufacturing constraints include lower yields, limits on advanced lithography tools, and bottlenecks in high bandwidth memory and packaging.

- Software remains a key advantage for Nvidia, while Huawei is opening designs and tools to grow developer adoption.

- Many analysts expect China to reach self sufficiency in midrange workloads within about five years, with parity at the high end likely to take longer.