A visa built to attract talent, met with online outrage

China has launched a new K visa aimed at young professionals in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). The rollout on October 1 sparked a fast and fierce reaction at home. The program is intended to widen China’s door to global talent at a time when the United States is raising barriers. Inside China, the launch collided with a tough job market for graduates, igniting concerns that foreign newcomers could add pressure to a fragile employment landscape.

- A visa built to attract talent, met with online outrage

- Inside the K visa, promise and unanswered questions

- Why it hit a nerve among young jobseekers

- Geopolitics and a global race for talent

- Standards, screening, and integration

- What officials and commentators are saying

- Who could benefit if the policy works

- What to watch as rules roll out

- Key Points

The debate exploded across social media. Hashtags tied to the K visa drew hundreds of millions of views within days. Many commenters questioned the logic of inviting more STEM graduates from abroad while domestic youth unemployment remains elevated. Others argued the country needs targeted global expertise to advance in areas like semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and biotech, especially as American export controls push China to build its own capabilities.

State media stepped in to calm the anger, saying the K visa is not a shortcut to immigration and that the policy reflects confidence in China’s scientific and technological goals. Yet uncertainty has fed the backlash. Diplomatic missions had not published full application details by midweek, and the timing overlapped with an eight day national holiday. That left open many basic questions about who qualifies and what activities the visa allows.

Inside the K visa, promise and unanswered questions

Official descriptions say the K visa targets young people with a bachelor’s degree or above in STEM from well known universities or research institutions in China or abroad. It also applies to those teaching or conducting research at such institutions. Unlike many existing categories, applicants do not need a job offer or an inviting organization in China before applying. Holders are expected to have more flexible entries, validity, and length of stay for activities tied to education, research, culture, entrepreneurship, and business.

The K visa differs from China’s R visa, which focuses on senior experts urgently needed by the state. It also contrasts with the US H-1B program, which requires employer sponsorship, faces an annual cap of 85,000 visas, and now carries a proposed 100,000 dollar application fee for new cases. By removing the employer requirement, China is signaling interest in early career talent and in students already in the country who want a path to remain after graduation.

Key parts of the rulebook remain unclear. State media have said the K visa is not a simple work permit. The People’s Daily urged readers not to equate it with immigration. Chinese embassies and consulates are expected to clarify eligibility, rights, and procedures in the coming days. In the meantime, the label China’s H-1B, popularized by foreign coverage, has stoked expectations and fears that do not match the available information.

Without employer sponsorship, vetting will matter. Policymakers will need to define recognized degree programs, ensure credible proof of qualifications, and set conditions that prevent misuse. Clear procedures, transparent metrics, and measured issuance could reduce the risk of confusion and help the policy meet its stated goals.

Why it hit a nerve among young jobseekers

China’s young graduates have endured a bruising labor market. The official youth unemployment rate reached 18.9 percent in August, the highest since the statistic returned in late 2023 after a pause to adjust methodology. This year’s class is the largest on record, about 12.2 million new college graduates competing for finite white collar jobs. That has fueled intense interest in civil service exams and a growing mismatch between degrees and available roles.

China has trained a large cohort in science and engineering. Roughly half of graduates across the last decade studied STEM fields, building a domestic pool of around 24 million. Yet job creation in advanced industries has not kept pace with the surge in degrees. Many graduates have taken delivery, sales, or temporary work while continuing to hunt for roles aligned with their training.

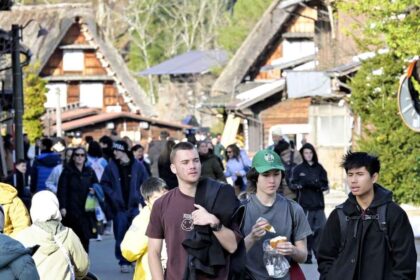

Against that backdrop, the idea of attracting more STEM graduates from abroad feels threatening to many. Some fear foreign degree holders will be preferred for scarce research roles or take entry level positions that local graduates want. Others worry that a bachelor’s degree as a baseline is too low a threshold for a policy billed as a talent magnet. Public anxiety has been heightened by a minority of xenophobic posts, with particular hostility toward potential Indian applicants. That online ugliness reflects a sensitive national conversation about jobs, identity, and openness.

A tight job market by the numbers

China’s graduate cohort has grown faster than the economy’s ability to absorb them into high skill roles. The manufacturing sector has cycled through periods of weak demand, private investment has been cautious, and broader urban unemployment has stayed elevated. Even as research labs and tech parks expand, hiring remains selective. Foreigners account for less than one percent of China’s population, around 845,000 residents in 2020, which suggests that any near term K visa intake would be small relative to the domestic talent pool. That scale may not soothe the immediate anxiety that many graduates feel as they send out resumes.

Language is another filter. Many scientific jobs in China require strong Mandarin in the lab and the office. That limits direct competition for roles where communication with suppliers, regulators, and customers happens in Chinese. Top research institutes often recruit globally, yet the majority of foreign academics who have moved successfully in recent years have been ethnic Chinese or speakers with advanced language skills.

Geopolitics and a global race for talent

Beijing’s timing is not accidental. The United States has moved to raise the cost of employer sponsorship for H-1B visas to 100,000 dollars for new applications. US agencies also added a 30 dollar fee for EVUS, a system that requires certain Chinese nationals to update travel information before entry. The message from Washington is tighter control. China is pointing the other way, telling STEM students and researchers that they have options in its labs, startups, and joint campuses.

China’s technology ambitions have sharpened under pressure from American export rules that restrict access to advanced chips, equipment, and know how. Leaders want to build domestic capacity in semiconductors, AI, clean energy, and advanced manufacturing. The K visa sits alongside measures like longer visa free stays for some travelers and targeted recruitment programs for scientists. The signal is that China will compete for global brains, even if movement between the two systems is getting harder.

Universities with joint programs and global partnerships could be early adopters. Foreign graduates in China often struggled to find legal pathways to remain after finishing degrees. The K visa could give them a bridge into internships, research assistantships, or early stage entrepreneurship, particularly in free trade zones and science parks where local governments court investment and recruit teams.

Standards, screening, and integration

Public debate has zeroed in on standards. Critics ask whether a bachelor’s degree is a meaningful screen for top tier talent. Some argue a master’s degree or research track record should be the minimum. Policymakers could reduce speculation by publishing a list of qualifying institutions, recognized fields, and any age or experience thresholds. They could also outline how achievements like patents, publications, and competition awards will be assessed.

The lack of employer sponsorship raises practical questions. Governments often rely on company petitions to validate job offers, confirm salaries, and tie visas to genuine roles. Without that anchor, Chinese authorities may need to strengthen document checks, education verification, and interviews. Clear rules that penalize fraud, along with cooperation between ministries and universities, can keep the system credible.

Integration is a separate challenge. Many foreign researchers struggle with Mandarin in daily life and at work. Workplace norms, collaboration styles, and expectations around publishing can differ from those in North America or Europe. China’s political environment also shapes research agendas and public discourse, which matters to scientists used to academic freedom and open debate. Successful programs elsewhere pair visas with language support, mentoring, and compliance guidance so that newcomers and employers do not talk past each other.

Social acceptance matters too. Spikes of online xenophobia discourage qualified applicants and make it harder for those already in China to build careers. Officials and universities can reinforce that selection will be fair, that the rule targets specific gaps, and that discrimination has no place in hiring or campus life. Public confidence grows when rules are clear and applied consistently.

What officials and commentators are saying

Beijing has tried to reframe the conversation around the K visa as part of a strategic plan, not a giveaway. Officials have stressed that China needs high skill talent and that the measure is limited in scope. State outlets have also argued that the public has been misled by rumors and labels that do not match the text of the policy.

A spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry welcomed global expertise in broad terms and encouraged professionals to build careers in China. The spokesperson said:

China welcomes talents from various sectors and fields across the world to come and find their footing in China for the progress of humanity and career success.

The People’s Daily, the official newspaper of the Communist Party, criticized the tone of online debate and urged readers to focus on the intent of the policy rather than false claims. In its editorial, it said:

Some people have misinterpreted and misunderstood the policy, spreading bizarre theories that mislead the public and create unnecessary anxiety.

Hu Xijin, a well known commentator and former editor of the Global Times, urged a practical approach. He argued that the core problem is weak demand for talent at home and that selection must be careful. Hu wrote:

The real issue at the heart of the K-visa controversy is that it reflects the tension in the domestic job market and the anxiety young people face in finding employment.

Analysts expect China to keep the program targeted rather than expansive. Issuance will likely focus on fields where domestic supply is thin and on candidates with proven potential. That would limit any impact on the broader job market while still sending a signal that China wants to compete for skilled people.

Who could benefit if the policy works

Several sectors are clear candidates. Chip design and manufacturing need specialized engineers and tool experts. Clean energy companies require battery chemists, power electronics engineers, and grid planners. AI and software firms hire applied researchers and large scale computing specialists. Biotech companies need lab scientists and regulatory talent. If the K visa lowers friction for early career hires and postgraduates, employers in these fields could fill narrow skills gaps faster.

Universities and national laboratories could also gain. The K visa may help recruit postdocs and research assistants into labs that work with global partners. Joint campuses that graduate foreign students each year could retain more of that talent, reducing churn and building research continuity. Local governments that run science parks and free trade zones may craft complementary incentives to attract targeted teams.

Even with those gains, the scale will remain modest against China’s domestic pipeline. The country produces millions of STEM graduates annually. A selective K visa will add niche capabilities, not a surge of competition for entry level jobs. Success will be judged less by volume and more by whether recruits meaningfully contribute to projects that raise productivity and help train local teams.

What to watch as rules roll out

Clarity on rights and conditions will shape public acceptance. Applicants, employers, and universities need to know whether K visas allow paid employment, internships, or only exchanges. Authorities should specify validity lengths, maximum stays, permitted activities, and any limitations by sector. Policymakers can also state whether there are quotas or city level targets and how applications will be prioritized.

Transparency will help. Publishing issuance numbers, approval rates, and fields of study can build trust that the program is targeted and fair. Strong anti fraud measures, education verification, and penalties for intermediaries that game the system will prevent abuse. Coordination with universities and science parks can streamline onboarding and compliance.

Support for integration can reduce friction for all sides. Language training, workplace orientation, and guidance for employers on contracts, social insurance, and academic credit help set expectations. Wage and labor standards should ensure foreign hires do not undercut compensation for local graduates. That keeps competition healthy and focused on skills.

Communication will shape outcomes. Young jobseekers want proof that domestic job creation remains the top priority. Clear messaging that talent policies serve specific research and industry goals, plus a consistent stance against xenophobia, can lower the temperature of online debate. China has fewer than one million foreign residents today, and any K visa intake will be small. A steady rollout paired with visible progress on high quality jobs at home would make the program easier to accept.

Key Points

- China launched a new K visa on October 1 targeting young STEM graduates and researchers without requiring employer sponsorship.

- The rollout triggered a domestic backlash amid a weak job market, with the official youth unemployment rate at 18.9 percent in August.

- State media said the policy is not immigration and urged the public to ignore rumors and mislabels.

- Key details are still pending from embassies, including whether K visas permit paid work and how long holders can stay.

- The K visa contrasts with the US H-1B system, which requires employer sponsorship and faces a proposed 100,000 dollar application fee for new cases.

- Concerns focus on standards, vetting without employer backing, language barriers, and social acceptance for newcomers.

- Officials say China welcomes global talent, while commentators argue job creation at home remains the central challenge.

- Sectors likely to benefit include semiconductors, AI, clean energy, advanced manufacturing, and biotech.

- Analysts expect issuance to be tight and targeted, limiting any immediate impact on the wider job market.

- Greater transparency, clear rules, and integration support will determine whether the program gains public trust.