Why this agreement matters now

Bangladesh is moving toward a landmark defense agreement with Turkey that would bring the SIPER long range air defense system to Dhaka and open the door to co production of Turkish combat drones. Negotiations are in the final stretch, according to officials involved, with a package that pairs new technology with training and potential local industrial work. If completed, the arrangement would give Bangladesh its first credible area air defense and a domestic pathway into unmanned aviation, reshaping the security picture around the Bay of Bengal.

- Why this agreement matters now

- What Bangladesh is expected to acquire

- Drones and the push for local production

- Turkey’s strategy and integrated air defense vision

- What it means for India

- The Myanmar factor and airspace violations

- Timelines, budget and integration hurdles

- Modernization strategy and the supplier mix

- Risks, limits and regional stability

- Key Points

Security pressures have been building. The civil war in neighboring Myanmar has repeatedly spilled over the border, from stray shells landing on Bangladeshi soil to military aircraft straying into Bangladeshi airspace. Dhaka’s legacy defenses are geared for short range threats and are not designed to counter high altitude incursions or a sustained air campaign. Key national nodes, including the capital, Chattogram port and energy infrastructure, remain vulnerable to modern aircraft, cruise missiles and armed drones.

Bangladesh’s leaders also have an eye on long term stability with India. Relations are functional, and trade and connectivity have grown. Still, any military planner in Dhaka must account for the imbalance in capability with the region’s dominant power. The goal is not parity, it is credible deterrence. A layered air defense and a capable drone arm shift the calculus by raising the cost and complexity of any hostile act while giving policymakers better surveillance and faster response options.

For Turkey, the partnership would advance its emergence as a global defense supplier. Ankara markets near NATO standard equipment without the strict political conditions that often accompany Western systems, and it couples sales with technology transfer and joint work. That mix is attractive to mid sized states seeking both capability and autonomy. For South Asia, Turkish entry through Bangladesh adds a new vector to regional security, distinct from established Chinese and Russian channels.

Recent high level military diplomacy underscores the momentum. Bangladesh’s air chief traveled to Turkey for official meetings with the Turkish Air Force and defense industries, part of a series of talks on cooperation, training and equipment that set the stage for a comprehensive package.

What Bangladesh is expected to acquire

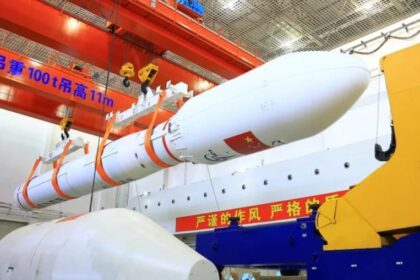

The core of the package centers on a layered air defense concept. Turkey’s SIPER is designed as a long range interceptor with a reach beyond 100 kilometers, intended to engage aircraft, certain cruise missiles and other aerial targets at significant altitude. It would likely be paired with a medium range layer, such as the Turkish Hisar O Plus, which provides coverage in the tens of kilometers and is suitable for helicopters, unmanned systems and low flying aircraft. Together, these systems would give Bangladesh an integrated shield for key regions rather than point defense alone.

SIPER at a glance

SIPER is Turkey’s flagship indigenous long range surface to air missile system developed by Roketsan and Aselsan. It uses networked radars and command systems to detect and track multiple targets and can work with other sensors to form a larger air defense picture. The interceptor uses guidance that blends mid course updates from ground systems with terminal homing to refine the final approach to the target. The system launches vertically, which allows 360 degree coverage without mechanically pointing the launcher. A battery consists of command and control vehicles, search and engagement radars, and multiple launchers, all tied by secure datalinks.

Building a layered shield

Bangladesh already fields short range systems designed to counter low altitude threats at close distances. A modern medium range layer would bridge the gap between those systems and SIPER, creating depth against a mix of targets, from drones to fast jets. In practice, such a posture uses overlapping coverage zones. Short range units protect critical assets and the air defense network itself, medium range batteries extend the protective bubble across key corridors, and the long range tier reaches into the outer approaches to keep high value targets at risk before they threaten cities or infrastructure. A layered posture also reduces the chance that a single tactic or decoy can overwhelm the entire shield.

Mapping these tiers to Bangladesh’s geography shows the impact. A SIPER battery near Dhaka could cover air approaches well beyond the capital’s perimeter. A similar setup in the southeast would strengthen protection over Chattogram and the Cox’s Bazar region, where refugee camps and border outposts have been under stress from the Myanmar conflict. With networking and data fusion, commanders could cue interceptors from the best sensor available, not just the radar co located with a given launcher. That is the key difference between a modern integrated air defense and a collection of standalone missiles.

Drones and the push for local production

The second pillar of the talks is unmanned aviation. Turkey has proposed establishing a joint drone facility in Bangladesh. The plan envisages delivery of armed drones together with options to assemble or co produce airframes and subsystems locally, and to train crews and maintainers. Turkish drones, including the Bayraktar family, have been employed across several battlefields for surveillance, target acquisition and precision attack. For Bangladesh, the value lies in persistence over land and sea, the ability to patrol border zones and maritime approaches for long periods, and the fast delivery of small precision munitions if needed.

Co production would begin to cultivate a local ecosystem. A facility in Bangladesh could handle final assembly, testing, and eventually the fabrication of airframe components and ground control systems. It would also allow the country to stock spares and keep aircraft flying without long waits for shipments. Over time, local technicians gain experience in avionics integration, secure communications, and data link maintenance, skills that translate to other defense and civil aerospace projects. This is how a buyer moves from a user to a partner with influence on future upgrades.

Growing industrial exchange is already visible in other niches. Turkish companies have signed contracts to furnish communication and power systems for Bangladeshi military infrastructure. These are enabling technologies, the connective tissue that supports larger equipment. They also reflect a trend toward long term cooperation that extends beyond a single purchase.

Turkey’s strategy and integrated air defense vision

Ankara has spent years building capacity across radars, missiles, armored vehicles, naval platforms and unmanned systems. After political friction with the United States over the Russian S 400 led to removal from the F 35 program, Turkey accelerated efforts to reduce reliance on foreign suppliers. The government now promotes a vision of self sufficiency backed by export success, with South and Southeast Asia seen as priority regions for partnerships under a broad Asia policy.

Turkey recently showcased an integrated air defense network that links sea and land based sensors and interceptors into a common operating picture. At a public unveiling of this network, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan framed air defense as a foundation of national security and a marker of technological independence.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said that no country can look to its future with confidence without developing its own radar and air defense systems.

The Bangladesh talks serve that vision. Securing a first export customer for SIPER would validate the system in a competitive market where American, Russian and Chinese options are well established. A presence in Bangladesh also anchors Turkey’s defense diplomacy on the Bay of Bengal, tying into broader outreach across the Indian Ocean, from maritime exercises to technology cooperation.

What it means for India

India remains the predominant military power in South Asia. A SIPER equipped Bangladesh does not change that. It does change planning assumptions. Airspace denial over key Bangladeshi sites would complicate any coercive option and raise the threshold for air operations that violate Bangladeshi sovereignty. Even if such scenarios are unlikely, serious armed forces plan for unlikely events, and they update those plans when neighbors gain new tools.

The provider matters. New Delhi has experience countering Chinese inroads among neighbors through diplomacy, connectivity, and defense offers of its own. A Turkish footprint is a different challenge. It reduces Dhaka’s dependence on Chinese weapons, which India may quietly welcome, yet it adds a capable NATO country with its own interests to the neighborhood. That mix could spur more engagement by India with Bangladesh to keep channels open on border management, river issues and economic integration.

The Myanmar factor and airspace violations

The conflict in Myanmar is a direct catalyst. Over recent years, shells and small munitions have crossed into Bangladesh during fighting between the Myanmar military and resistance groups. At times, aircraft from Myanmar have strayed into Bangladeshi airspace, prompting protests. The presence of large refugee camps near Cox’s Bazar, housing people who fled violence in Rakhine State, adds humanitarian risk to any escalation near the frontier.

Layered air defense would give Dhaka more than a protest note. With better surveillance and a credible intercept option, Bangladesh can track violations in real time and respond proportionately. The point is not to invite confrontation but to deter repeat incidents by making incursions costly and uncertain. The same sensors and command systems help in peace time too, cueing patrols and providing a persistent picture over sensitive border zones.

Timelines, budget and integration hurdles

Negotiations are close to the finish line, yet final budget and financing details still need resolution. Long range air defense is a major investment. The price tag includes radars, command vehicles, launchers, missiles, training, spares, simulators and depot tools. Delivery schedules are often staggered, with initial operating capability reached after crews complete courses and live fire events. Full integration, with national early warning radars and civil aviation coordination, can take several years.

Integration is the hard part. A modern air picture blends data from multiple radars, ADS B feeds, and friendly aircraft transponders to avoid misidentification. Track correlation, deconfliction and rules of engagement must be codified and rehearsed. Communications need redundancy and encryption. The more complex the network, the more it depends on disciplined procedures and resilient power and data links. Many of these requirements are as much organizational as they are technical.

Drones bring their own demands. To get the most from unmanned systems, Bangladesh will need secure data links, trained imagery analysts, and a concept of operations that turns airborne video and radar into quick, useful action for border guards, coast guard units and army formations. Local assembly and maintenance will help shorten downtime, but stocks of batteries, engines and gimbals must be planned with care to keep sortie rates high.

Modernization strategy and the supplier mix

The air defense talks fit within a broader modernization program known as Forces Goal 2030. Over the past decade, Bangladesh has expanded its army formations, built out its navy with submarines and new surface ships, and refreshed its air force with upgraded radars and aircraft. Much of this inventory came from China, with additions from Russia, Western countries and Turkey. The government has also explored options for new fighter aircraft, with reporting pointing to interest in the Chinese J 10C among other candidates.

Diversification is the guiding theme. Dhaka aims to balance ties with China, India, the United States and now Turkey, reducing single supplier risk while maximizing technology transfer. Turkey’s offer of near NATO grade systems plus joint production aligns with that approach. China will remain a central supplier, given deep ties and cost advantages, and cooperation with both suppliers is likely to continue under the interim leadership that replaced the previous administration. The end goal is a stronger force that can protect sovereignty without binding Bangladesh to any bloc.

Industrial cooperation is an important piece. Domestic shipbuilding has advanced, and Turkish firms have begun supplying communications and power systems for military use. If a drone facility is approved, Bangladesh will gain a foundation for long term unmanned aviation, with spillovers into electronics, training and testing that benefit civil sectors as well.

Risks, limits and regional stability

An air defense network is not a magic shield. Its performance depends on training, readiness, and smart doctrine. Adversaries adapt with low altitude routes, decoys and saturation tactics. That is why layering, mobility and realistic exercises are essential. For drones, the risk is overconfidence if sensors are not integrated with patrols on the ground. Data must flow to the right unit at the right time, or persistent surveillance will not translate into better security.

Handled well, the Turkey Bangladesh package can reduce the chance of miscalculation by clarifying the costs of violation and giving Dhaka non escalatory tools to monitor and signal. The strategic picture is dynamic, with India, China and Myanmar all watching closely. Constructive military to military contacts and clear communication protocols will help ensure that new capability supports stability rather than tension.

Key Points

- Bangladesh is close to a defense agreement with Turkey that would bring SIPER long range air defense and open co production of armed drones.

- The deal aims to close gaps exposed by Myanmar’s conflict and repeated airspace violations while improving deterrence against more capable adversaries.

- SIPER offers coverage beyond 100 kilometers, likely paired with a medium range layer such as Hisar O Plus to create a tiered shield.

- A joint drone facility would shift Bangladesh from a buyer to an industrial partner, building local skills, spares and sustainment capacity.

- Turkey’s strategy blends exports with technology transfer, and an anchor in Bangladesh advances its outreach across the Indian Ocean region.

- India retains military superiority, yet a credible Bangladeshi air defense raises the cost and complexity of any coercive option.

- Negotiations are advanced, with budget and integration details still to finalize, and full operational integration expected to take years.

- The package fits within Forces Goal 2030 and a broader push to diversify suppliers, balancing ties with China while deepening cooperation with Turkey.

- Success will depend on training, networking and doctrine, not just new hardware, to ensure the systems enhance security and reduce risks.