Two millennia of continuity in a fast changing economy

In an age when many corporations struggle to last a generation, a small group of Japanese firms have run for more than 1,000 years. Four of them sit at the very top of global longevity. Kongo Gumi, a temple builder founded in 578, and three ryokan inns, Nishiyama Onsen Keiunkan from 705, Sennen no Yu Koman from 717, and Hoshi Ryokan from 718, continue to operate today. Their stories combine craftsmanship, careful stewardship, and a clear sense of purpose. They also offer a window into why Japan has more century old companies than any other country and how tradition can live alongside innovation.

- Two millennia of continuity in a fast changing economy

- Kongo Gumi, master builders since the sixth century

- Nishiyama Onsen Keiunkan, the oldest working hotel

- Sennen no Yu Koman, a family inn tied to Kinosaki Onsen

- Hoshi Ryokan, endurance in Awazu Onsen

- Why Japan produces so many venerable firms

- Adaptation without losing identity

- Challenges facing venerable brands

- What to Know

These businesses did not drift through time by luck. They adapted while holding onto their identity. They kept leadership stable, often within families, and treated reputation as a precious asset. They stayed close to their communities and customers. They invested patiently, avoided reckless expansion, and updated tools and methods when it served their mission. The result is continuity that spans empires, wars, pandemics, and market cycles.

Kongo Gumi, master builders since the sixth century

Kongo Gumi began in 578 in what is now Osaka. Historical accounts describe master builders arriving to help construct early Buddhist temples, and the company’s first great project is linked to Shitennoji. Over the centuries, Kongo Gumi became a specialist in sacred architecture, designing, repairing, and preserving wooden structures that are central to cultural life. A 17th century family scroll documented 40 leaders in succession. That record hints at a core advantage that runs through Japan’s oldest firms: the ability to pass on knowledge and responsibility across generations.

Continuity never meant standing still. Temple carpentry depends on joinery skills and wood selection, but Kongo Gumi absorbed modern methods where helpful. The company explored reinforced designs that blend concrete with timber to safeguard historic buildings and adopted computer aided design long before many peers, which improved planning and precision without losing the spirit of traditional work. This balance of craft and technology allowed the firm to protect fragile sites and meet safety standards in a country prone to earthquakes.

In the early 2000s, heavy debts and a weak construction market forced a change. In 2006 Kongo Gumi became a subsidiary of Takamatsu Construction Group. The brand and specialization endured under new ownership. The company continues to work on cultural heritage projects, while drawing on group resources for finance and operations. Survival required flexibility, yet the mission stayed intact. That is a recurring theme among long lived Japanese companies.

Nishiyama Onsen Keiunkan, the oldest working hotel

At the foot of the Southern Alps in Yamanashi Prefecture, Nishiyama Onsen Keiunkan has welcomed travelers since 705. It grew around hot springs that have drawn guests for centuries. The inn operated under one family for 52 generations, then moved to a professional manager in 2017 as the family prepared a new phase of stewardship. The hotel holds 37 rooms, intimate baths fed by natural sources, and dining that reflects local ingredients and seasons.

Historical records and lore mention famous visitors, including daimyo Takeda Shingen and Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu. In recent years, members of the Imperial family have also stayed. Yet the core attraction is not celebrity history. It is the quiet flow of water, the mountain setting, and a service philosophy that Japanese hospitality calls omotenashi. Staff anticipate needs, respect privacy, and convey welcome without show. That cultural approach to care helps explain why ryokan inns can hold loyal guests for generations.

Keiunkan has modernized modestly, always with an eye to comfort rather than spectacle. Plumbing and heating systems were upgraded to sustain a reliable flow from the springs. Earthquake safety was strengthened. Rooms preserve a sense of simplicity, with tatami flooring, low tables, and views that open to nature. Guests experience a continuity of place that has lasted well over a thousand years.

Sennen no Yu Koman, a family inn tied to Kinosaki Onsen

Sennen no Yu Koman dates to 717 and stands in Kinosaki, a town built around hot springs on the Sea of Japan side of the country. Family chronicles trace its founders and their successors across 46 generations. The ryokan blends wooden architecture with baths that draw on the town’s thermal waters. Kinosaki is known for strolls in light yukata robes between public baths, seasonal seafood, and a compact layout that invites walking. Koman’s own baths and rooms sit within this network and heritage.

The business evolved with the town. As Kinosaki added public bathhouses and improved access by rail, Koman refined its accommodations and service, keeping its own identity while benefiting from the shared reputation of the resort. The ryokan’s records describe periods of rebuilding after floods and earth tremors, and the patience required to reopen in keeping with tradition. Guests who return over decades often remark on continuity in the welcome and the meals even as facilities quietly improve.

Hoshi Ryokan, endurance in Awazu Onsen

Hoshi Ryokan began in 718 in Awazu Onsen, Ishikawa Prefecture. It is frequently cited as the oldest continuously run family business. The inn encircles a Japanese garden. Guest rooms look onto water and stone, with pathways that lead to baths fed by the spring that first made the location attractive more than a millennium ago. Leadership passed through 46 generations of the Hoshi family, with each steward asked to balance protection of the house with necessary repairs and updates.

Hoshi has weathered wars, recessions, and changing tastes. At difficult moments, managers controlled costs, preserved staff, and focused on hospitality fundamentals rather than quick fixes. The garden and bath layout are adjusted with a light touch instead of dramatic overhauls. Visitors feel a link to history without sacrificing comfort. That sensibility, calm and consistent, explains why so many guests treat a stay at Hoshi as a family tradition.

Why Japan produces so many venerable firms

Japan has the highest concentration of very old companies on earth. Tens of thousands have operated for at least a century, and a smaller group measures age in many centuries. The reasons are cultural, legal, and economic. A key element is the concept of shinise, a term used for long lasting businesses that carry weight in their communities. Owners view the company as a legacy to pass on, not a vehicle for short term gain. Continuity and trust matter as much as profit. In practice, that stance shapes decisions about who leads, how much to borrow, what risks to take, and how to treat customers and neighbors.

Succession by design

Family ownership has been central for many of these firms, but succession is not narrowly defined by bloodline. Japanese tradition has long allowed adult adoption to fill leadership gaps and keep a business on a steady course. The practice, known as mukoyoshi when a son in law is adopted, makes it possible to choose a capable successor in the family framework. Research over the years has shown that adopted leaders can perform as well as, and often better than, sons who inherit by default. The result is a family enterprise with professional management discipline.

Service culture and trust

Shinise often operate in fields that rely on craft and service, such as inns, confectionery, tea, sake, and religious goods. In these settings, trust builds over years, not quarters. The customer expects continuity in quality and style. The firms anchor local identity by supporting festivals, preserving artisanal methods, and training apprentices. Owners describe their role as custodians of a place as much as operators of a business. That identity earns loyalty that helps carry them through hard times.

Patience and conservative balance sheets

Long lived firms rarely chase rapid expansion. Many avoid stock market listing to escape the pull of quarterly targets. They keep financial buffers, maintain modest debt, and accept slower growth in exchange for durability. They refine their core skills and update processes in measured steps. When change comes, they prefer reversible moves. This patience has served them in a country exposed to earthquakes and typhoons, boom and bust cycles, and shifts in tourism and trade.

Adaptation without losing identity

Longevity is not the same as refusing to change. Kongo Gumi updated design tools, reinforced structures without stripping their character, and chose partnership when debts made independence unsafe. Keiunkan and Koman refreshed rooms and utilities while staying true to the ryokan experience of baths, seasonal cuisine, and quiet surroundings. Hoshi managed downturns by protecting staff and core services, then welcoming guests back with the same calm rhythm of garden, water, and tea.

What adaptation looks like day to day

- Keep the core mission clear. Building sacred spaces, caring for guests in hot spring towns, or producing traditional goods remains the center of work.

- Update tools and materials where they strengthen safety, quality, or sustainability. Use modern design software, strengthen structures, or upgrade plumbing behind the scenes.

- Shape a customer experience that feels authentic. Preserve layouts, rituals, and ingredients that define place and craft.

- Diversify within competence during lean years. Take on related work that fits skills and brand rather than jumping to far off ventures.

- Invest in people. Train apprentices and staff so knowledge does not fade when a master retires.

- Build alliances when needed. Accept outside capital or join a larger group if it secures the legacy with minimal disruption to mission.

- Document heritage. Keep records, family chronicles, and design drawings so each generation starts with context and pride.

These practices do not guarantee survival, yet they make it more likely. They keep choices aligned with identity and reduce the odds of catastrophic missteps. They also create a buffer of goodwill. Guests forgive small imperfections when they feel respected and see care taken with place and craft.

Challenges facing venerable brands

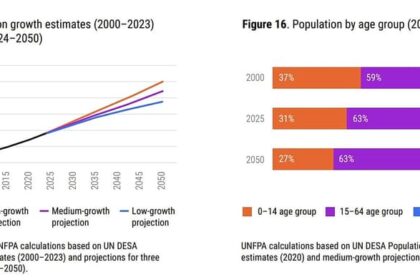

Demographics pose the hardest test. Japan’s population is aging and shrinking, especially outside big cities. Finding successors is harder than it used to be. Tourism swings with global events, as seen during the pandemic. Natural disasters can force closures or expensive repairs. Costs rise faster than room rates in some seasons. Builders face stricter codes and material shortages. Paper thin margins leave little room for errors.

There are reasons for confidence. A new generation of stewards is blending entrepreneurial skill with tradition. Some owners hire professional managers while preparing the next family successor. Training programs bring in artisans from outside the region. Digital tools streamline reservations, supply chains, and maintenance. Sustainability upgrades cut energy use without altering the guest experience. The common thread is clarity about what can change and what must stay the same.

What to Know

- Four Japanese firms are among the oldest operating companies on earth: Kongo Gumi (578), Nishiyama Onsen Keiunkan (705), Sennen no Yu Koman (717), and Hoshi Ryokan (718).

- Kongo Gumi specializes in Buddhist temple architecture, adopted modern design methods, and became a subsidiary in 2006 to secure continuity.

- Nishiyama Onsen Keiunkan runs 37 rooms around natural hot springs and moved to professional management in 2017 after 52 generations of family leadership.

- Sennen no Yu Koman has served guests in Kinosaki Onsen for 46 generations, balancing quiet upgrades with traditional ryokan hospitality.

- Hoshi Ryokan in Awazu Onsen is often cited as the oldest continuously run family business, with rooms arranged around a Japanese garden.

- Japan has the largest number of century old companies worldwide. Many are small or medium sized and embedded in their local communities.

- Longevity rests on clear identity, careful succession, conservative finance, and measured adaptation rather than rapid expansion.

- Adult adoption helps fill leadership gaps while keeping family stewardship intact, a practice that supports continuity.

- Service culture rooted in omotenashi and community ties builds trust that carries firms through downturns and disasters.

- Succession, demographics, and disaster risk remain key challenges, but steady updates and strong stewardship keep these legacies alive.