A new wave of detentions hits the private sector

On September 22, Great Microwave Technology, a Shanghai listed maker of radio frequency components, disclosed that its founder, Yu Faxin, had been taken away by China’s top anti corruption agency. Until recently he was known for advanced semiconductor work that supports military applications. His name is now linked to a different story. He is being held under liuzhi, an extra judicial form of custody that is increasingly ensnaring business leaders.

- A new wave of detentions hits the private sector

- What is liuzhi and who can be held

- The growing roster of missing bosses

- Politics and policy reshape the rules for big business

- Finance under strain, shadow banking under scrutiny

- Market reaction and the cost of uncertainty

- Legal risk, blacklists and the penalty for failure

- How entrepreneurs and investors are adapting

- What to Know

Yu’s situation fits a pattern that has become familiar in China’s markets. An executive vanishes from public view. A company filing says the board or colleagues cannot reach the person. Days or weeks pass with no official details. Sometimes the firm later announces that the person is cooperating with investigators. In other cases, the executive is tried and sentenced on corruption or financial charges. The quiet period in between fuels speculation, dents confidence, and leaves investors and employees in the dark.

The new round of disappearances spans technology, finance, real estate, and consumer industries. It arrives at a time when the leadership wants a more disciplined private sector, one that supports national goals and accepts tighter oversight. For entrepreneurs, the rules of success have shifted. Political risk and legal exposure now carry as much weight as product, revenue, and valuation.

What is liuzhi and who can be held

Liuzhi, which translates as retention in custody, is a tool created under the National Supervision Law (2018). It empowers the National Supervision Commission (NSC) and its local arms to detain and question people suspected of offenses linked to public power. The system covers Communist Party members, state employees, managers in public institutions and state firms, and private sector individuals whose work intersects with public functions. In practice, it reaches well beyond the party to contractors, suppliers, and business partners of public entities.

Liuzhi operates outside the criminal court system. Investigators can detain people at designated locations, question them without a lawyer present, and limit contact with family or colleagues. Detention can last for months. Under recent changes, agents can hold a person for up to eight months, and reset the clock if new suspicions arise. Rights advocates criticize the lack of transparency and judicial oversight. Chinese authorities portray liuzhi as a necessary anti corruption tool that breaks patronage networks and recovers stolen funds.

How liuzhi differs from criminal detention

Ordinary criminal detention is governed by the Criminal Procedure Law. Police need court oversight for extended holds, and suspects have clearer access to counsel. Liuzhi follows supervision law, not criminal law. The NSC can detain without court approval. After months of questioning, investigators can transfer a case to prosecutors. Statements and documents gathered during liuzhi may shape later charges. This parallel track gives party discipline inspectors broad reach into corporate and financial life.

The growing roster of missing bosses

Recent years delivered a steady stream of cases at the top of Chinese business. In early 2023, tech dealmaker Bao Fan, founder of China Renaissance, could not be reached by his firm. The company disclosed the loss of contact in a stock exchange filing, and its shares plunged as much as 50 percent. It later said he was cooperating with certain authorities. Bao eventually resigned from leadership posts, and the firm worked to stabilize operations as clients and partners reassessed risk.

High profile icons have also vanished. Alibaba founder Jack Ma dropped from public view in late 2020 after he criticized financial regulators. The planned listing of Ant Group, Alibaba’s finance affiliate, was halted. He resurfaced abroad and has maintained a low profile in China. Real estate tycoon Ren Zhiqiang disappeared after he attacked the leadership’s handling of the pandemic. He received an 18 year prison sentence on graft charges.

Some cases crossed borders. Financier Xiao Jianhua was taken from a Hong Kong hotel in 2017 and was later sentenced in mainland court to 13 years for financial crimes. Anbang Insurance’s former chairman, Wu Xiaohui, was tried in 2018 for fraud and embezzlement and received an 18 year sentence. Oil and finance figure Ye Jianming fell from view in 2018, and his status remains undisclosed. Others returned to work after brief absences, including Fosun’s Guo Guangchang and brokerage chief Yim Fung, who were said to be assisting investigators before resuming duties.

Outcomes vary

Some executives return subdued and stripped of titles. Others move aside while their firms appoint caretakers. A share of cases end in long prison terms. The absence of public information shapes outcomes for employees, lenders, and suppliers. When a chief executive cannot be reached, supply chains stall, credit lines tighten, and projects slip. Confidence suffers even if the person later reappears.

Politics and policy reshape the rules for big business

Party leaders have sent a consistent message to private companies. The state welcomes private investment, but it expects private power to align with national priorities. Regulators have tightened oversight of internet platforms, consumer fintech, online tutoring, gaming, and data security. A new financial regulator was created to oversee most of non bank finance, closing gaps that emerged when multiple agencies shared responsibility. The effort is sold as a way to limit risky behavior and prevent regulatory arbitrage.

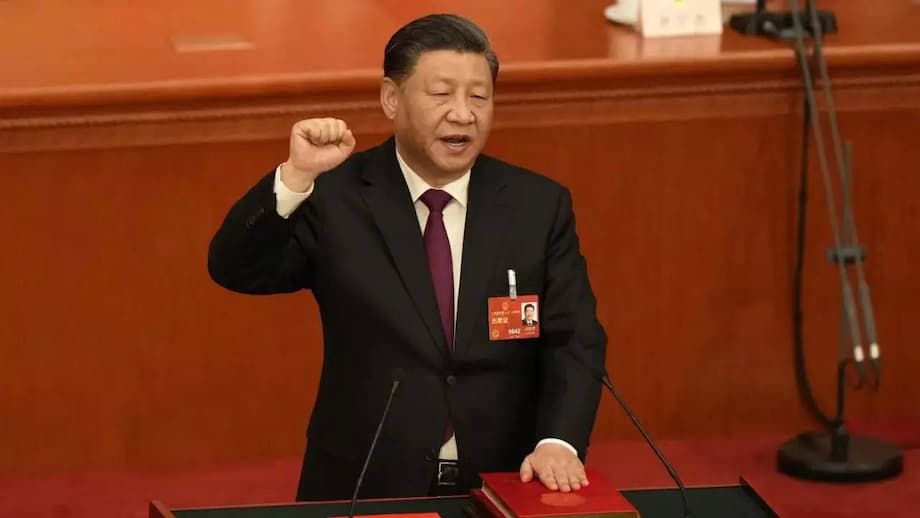

The leadership has paired enforcement with moral appeals. Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Communist Party and state president, framed the expectation this way:

Private enterprises and entrepreneurs should be rich and responsible, rich and righteous, and rich and loving.

Bankers and dealmakers also heard blunt warnings. Officials urged finance workers to avoid the culture of excess associated with Wall Street, and tightened rules on executive pay and bonuses. In the official view, these steps will reduce misaligned incentives and channel capital toward advanced manufacturing, social services, and projects that serve the real economy.

Finance under strain, shadow banking under scrutiny

Pressure on private finance has overlapped with a prolonged property slump and stress in off balance sheet lending. In late 2023, Zhongzhi Enterprise Group, one of the largest shadow banking conglomerates, told investors it was severely insolvent. Police in Beijing soon opened a criminal probe into its wealth arm and said they had taken compulsory measures against suspects. Around the same time, two executives at companies controlled by Zhongzhi investment units went missing, according to exchange filings by those firms.

Missed payments by a major trust linked to Zhongzhi sparked protests by angry investors. The episode revived anxiety that property losses could infect the wider financial system and that senior managers tied to trust products would face probes or detention while the government tries to contain fallout.

What shadow banking means

Shadow banking in China refers to credit that sits outside traditional bank loans. Trust companies, asset managers, and wealth products channel money from investors to developers and industrial borrowers. The sector is large, worth trillions of dollars. During the property boom, trusts funded ambitious projects. When sales fell and defaults rose, many trusts faced heavy losses. That stress made regulators more aggressive. It also raised the stakes for executives who steer these investment vehicles across complex rules and shifting enforcement priorities.

Market reaction and the cost of uncertainty

Markets react quickly when a boss goes missing. Listed firms rush to disclose the loss of contact. Traders often sell first. Banks recheck exposure to affected companies and their affiliates. Deal flow slows as lawyers and compliance officers search for clarity. Foreign investors price a higher premium for political and legal risk in valuations and credit spreads.

The chilling effect lingers after headlines fade. Board members travel less and keep smaller public profiles. Investor relations teams have little to say when cases fall under secrecy rules. Overseas partners demand stronger compliance covenants, escrow protections, and step in rights. Career bankers and tech founders weigh the benefits of scale against the exposure that public prominence brings in a system that punishes missteps harshly.

Legal risk, blacklists and the penalty for failure

Alongside detentions, China’s national credit blacklist has expanded as courts and regulators enforce unpaid debts. Individuals placed on the list lose access to flights and high speed trains. They face restrictions on hotel stays, private schools, and many forms of consumption. The designation makes it hard to obtain credit, sign contracts, or even book decent travel. For entrepreneurs whose firms fail, the personal consequences can be severe.

By September 2024, roughly 200,000 people had been added to the blacklist, compared with about 17,400 in 2019, with nearly half of the new entries tied to business disputes. Bankruptcy law remains patchy in practice, so many commercial failures end in blacklisting rather than orderly restructuring in court. Public reports have linked several executive suicides to the pressure of investigations and debt enforcement. In this climate, risk taking looks less attractive just as policymakers call for innovation and private investment.

How entrepreneurs and investors are adapting

Private firms are adjusting to the new era. Many are building in house compliance teams, elevating risk officers, and running internal audits that mirror the approach used by state inspectors. Some founders step back from public roles while professional managers handle regulatory engagement and external communications. Others register more functions in multiple jurisdictions so the company can continue operating if one leader is detained.

International companies with China exposure are revisiting staffing and data policies. Several global consultancies and due diligence firms have faced raids or staff detentions. Security teams are rewriting travel protocols for employees who work on sensitive sectors such as finance, data services, or defense related technology. A growing number of foreign executives schedule trips to avoid political set pieces, when controls tighten and inspections surge.

For domestic entrepreneurs, the safest path is to align with state goals such as advanced manufacturing, green energy projects, and rural revitalization. That does not eliminate risk. It gives companies a clearer story to present to regulators and investors if scrutiny comes. The calculus is sober. Growth plans are trimmed to fit a balance between ambition and exposure to investigations that can arrive without warning.

What to Know

- Great Microwave Technology disclosed on September 22 that founder Yu Faxin was taken by anti corruption investigators and placed under liuzhi.

- Liuzhi is a retention in custody system created by the National Supervision Law (2018) that allows detention outside criminal courts.

- Detention under liuzhi can last months, up to eight months under recent changes, with limited access to counsel.

- Cases range from brief absences to long prison terms, with some executives returning subdued and others convicted on graft or financial charges.

- High profile examples include Bao Fan, Jack Ma, Ren Zhiqiang, Wu Xiaohui, Xiao Jianhua, and Ye Jianming.

- Shadow banking stress, highlighted by Zhongzhi’s insolvency and police probe, has coincided with more disappearances in finance.

- A new financial regulator now oversees most non bank finance as part of a wider tightening of control over private capital.

- Liuzhi detentions rose sharply in 2024, to about 38,000 cases, while national credit blacklists expanded to roughly 200,000 new entries by September.

- Market reactions to disappearances can be severe, with share prices plunging and credit lines tightening on disclosure.

- Companies are responding with stronger compliance, quieter public profiles, and closer alignment with state priorities.