The DeepSeek Shockwaves Still Reverberate

One year after DeepSeek’s mobile app emerged from Hangzhou to rattle Silicon Valley, the artificial intelligence landscape has split into two parallel universes. In January 2025, the Chinese startup demonstrated that large language models could rival ChatGPT in performance at a fraction of the cost, using less-advanced chips and a fraction of the budget. The incident, now simply called “the DeepSeek moment” in tech circles, exposed vulnerabilities in American AI dominance that continue to reshape global technology competition as 2026 begins.

The shock was not merely technical but psychological. American venture capital had poured $175 billion into AI during 2025, nearly thirty times the $6 billion invested by Chinese firms, according to data from China International Capital Corp. Yet DeepSeek proved that resource constraints could breed innovation rather than stifle it. Scott Singer, a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, observes that the episode opened a new chapter in strategic competition. “China is definitely positioning itself rhetorically as a multilateral, open, and development-focused global leader,” he explained. “China’s geopolitical positioning on AI predates the Trump administration, but it increasingly resonates with global audiences.”

Washington Bets on Chips, Beijing Counters with Code

The Trump administration responded to DeepSeek’s challenge with a strategy document titled “Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan,” published in mid-2025. The plan framed the competition in stark zero-sum terms, declaring that the United States is in a contest for “global dominance in artificial intelligence.” The administration called for rolling back regulatory barriers and leveraging American technological dominance by exporting the “full AI technology stack” to allies, including hardware, models, software, and standards. The unstated target was China, which Washington seeks to isolate from the global AI supply chain.

Washington’s confidence rests on a single critical advantage: control of the world’s most advanced semiconductors. Nvidia, headquartered in Silicon Valley, designs the graphics processing units that power frontier AI models. American firms currently enjoy a seven-month lead over Chinese competitors in cutting-edge capabilities, maintained through strict export controls on high-end chips and semiconductor manufacturing equipment. Huawei’s Ascend series represents China’s best domestic alternative, with the Ascend 910 performing at roughly 60 percent of the capability of Nvidia’s older H100 chips on basic tasks like text generation, though falling further behind on complex model training.

However, this technological moat faces unexpected erosion. In December 2025, the Trump administration announced a controversial reversal, allowing Nvidia to sell its H200 series chips to vetted Chinese buyers in exchange for a percentage of sales revenue. The administration excluded the most advanced Blackwell and Rubin chips, betting that China would develop dependency on older American technology rather than accelerate domestic alternatives. Critics warn this strategy risks backfiring. Chinese firms including Alibaba, Tencent, and ByteDance have already placed orders exceeding two million H200 chips valued at over $50 billion, according to industry estimates. Last week, Reuters reported that Chinese customs officials instructed domestic companies to reject shipments, suggesting Beijing recognizes the trap and refuses dependency.

The Open-Source Offensive

While the United States controls the hardware layer, China has launched a sophisticated assault on the software layer through open-source artificial intelligence. Unlike the closed, proprietary models maintained by OpenAI and Anthropic, Chinese firms have released “open-weight” models that allow developers to download, modify, and deploy AI systems freely. These models, including DeepSeek’s R1, Alibaba’s Qwen family, and Moonshot AI’s offerings, have gained massive global traction.

Alibaba’s Qwen models have become the most downloaded open-weight AI systems worldwide, with approximately 700 million downloads tracked by the Hugging Face platform. The Qwen ecosystem spans nearly 400 distinct models spawning over 180,000 derivative versions customized for specific applications. This strategy targets precisely the markets Washington hopes to influence: price-sensitive developing economies seeking AI capabilities without Western export restrictions or licensing fees.

Chinese President Xi Jinping explicitly linked this technological progress to national rejuvenation in his 2026 New Year’s address, declaring that Chinese tech had “reached new heights” with breakthroughs in indigenous chip development. The rhetoric connects contemporary AI competition to China’s “century of humiliation,” the period from the mid-19th century Opium Wars until 1949 when technological backwardness left China vulnerable to foreign powers. Beijing views artificial intelligence as the decisive technology that will determine whether history repeats itself or reverses.

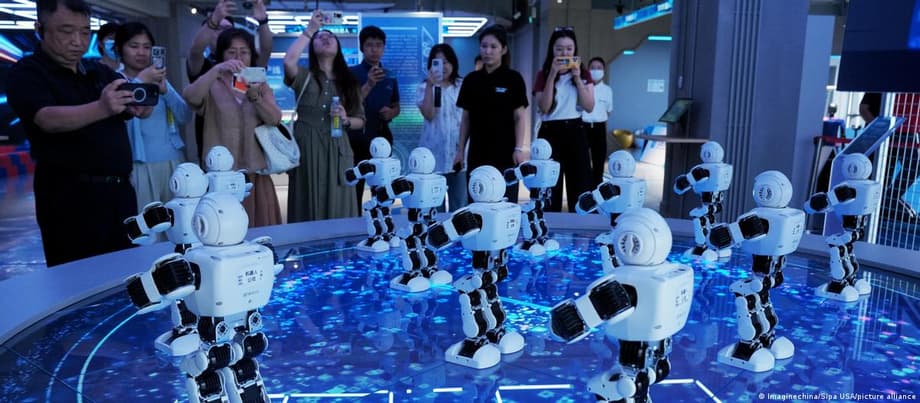

The divergence in strategy is stark. The United States pursues frontier performance, building ever-larger data centers and training massive models requiring unprecedented computing power. China focuses on diffusion, embedding “good enough” AI into manufacturing, robotics, and physical infrastructure through the “AI Plus” initiative. This program aims to embed artificial intelligence across industry, healthcare, and governance by 2035, creating what Beijing terms a “fully AI-powered” society.

The Infrastructure Bottleneck

Both superpowers face severe constraints that will determine the pace of AI development through 2026, but their bottlenecks differ fundamentally. The United States possesses technological superiority but confronts a power crisis. Training frontier AI models requires massive data centers that strain electrical grids already operating near capacity. American cloud providers are projected to spend $600 billion on AI infrastructure in 2026, double their 2024 expenditure, yet power availability and construction timelines pose hard limits on expansion.

China confronts the mirror problem. While Beijing possesses abundant energy resources, including twice the electrical generation capacity of the United States according to Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, it lacks the advanced chips required to utilize that power for AI training. Huang, speaking at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, noted that while American chip technology remains “generations ahead,” Chinese construction capabilities far outpace American efficiency. “If you want to build a data centre here in the United States from breaking ground to standing up an AI supercomputer is probably about three years. They can build a hospital in a weekend,” Huang said, highlighting how infrastructure deployment speed could compensate for technological gaps.

This divergence creates what analysts call “asymmetric competition.” The United States leads in theoretical capabilities and cutting-edge research, while China dominates in implementation speed and physical world applications. Scott Singer notes that Chinese tech hubs display “much more excitement and energy around leveraging AI as it is today” rather than pursuing speculative future breakthroughs. This practical focus manifests in AI-powered robotics, smart manufacturing, and autonomous systems where China appears to be pulling ahead of Western counterparts.

Military Dimensions and the Diffusion Race

The competition extends beyond commercial markets into military applications, where speed of adoption may prove more decisive than technological sophistication. The United States Department of Defense has launched an aggressive “AI-first” strategy centered on seven “Pace-Setting Projects” designed to accelerate deployment across warfare, intelligence, and enterprise functions. Projects like “Swarm Forge” and “Agent Network” aim to integrate AI into battle management and decision support systems, while “Ender’s Foundry” focuses on AI-enabled military simulation.

Yet the Pentagon faces bureaucratic friction that China avoids through military-civil fusion, a system that seamlessly channels civilian AI advances into military applications. Research by Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology analyzing over 2,800 People’s Liberation Army contracts reveals a defense ecosystem anchored by state-owned enterprises but increasingly drawing from private sector innovators. While the United States struggles with accreditation timelines and data silos, China’s centralized system can mandate adoption across military and civilian domains simultaneously.

The stakes involve autonomous weapons, electronic warfare, and command-and-control systems that could determine the outcome of future conflicts. A recent Council on Foreign Relations analysis warns that 2026 represents a decisive phase where AI systems transition from experimental tools to autonomous agents capable of executing complex military operations with minimal human oversight. Chinese state-sponsored cyber operations have already demonstrated AI agents autonomously executing 80 to 90 percent of intrusion workflows, according to security researchers.

Global Governance and the Standards War

Beyond raw capabilities, the US-China competition encompasses a struggle to define the rules governing artificial intelligence globally. In 2026, the United Nations hosts the Global Dialogue on AI Governance, creating the first truly global forum for coordinating standards, risks, and norms. However, fundamental philosophical divides threaten to fragment rather than unify the international order.

The European Union pushes a rights-based regulatory model emphasizing individual privacy and algorithmic transparency. The United States favors voluntary standards that preserve innovation flexibility. China promotes “inclusive cooperation” while defending state control over data and deployment. The result, according to Atlantic Council analysts, will likely produce “global governance in form but geopolitical in substance,” with coordination on scientific assessments coexisting alongside rival national strategies.

China’s diplomatic positioning emphasizes openness and multilateralism, contrasting with Washington’s “America First” rhetoric. Beijing’s 2025 Global AI Governance Action Plan explicitly called for a “diverse, open, and innovative” ecosystem leveraging multiple stakeholders. This messaging resonates particularly in the Global South, where export controls and licensing fees make American AI inaccessible. Nearly 80 percent of China experts surveyed by the Mercator Institute for China Studies expect Beijing to make major advances in diversifying export markets and deepening partnerships with developing nations during 2026.

Meanwhile, the United States pursues “tech-stack diplomacy,” offering AI infrastructure partnerships to allies willing to adopt American standards. The Trump administration has framed this as a security imperative, warning that Chinese technology creates dependencies that adversaries could exploit. However, American diplomatic efforts face headwinds from trade disputes and demands that allies align with Washington’s restrictive export policies.

The Reality Check: Multiple Races, No Finish Line

Analysts increasingly reject the metaphor of a single “AI race” with a definitive winner. Instead, the competition resembles a decathlon, encompassing multiple overlapping domains with different victors. The United States maintains commanding leads in semiconductor design, frontier model capabilities, and cloud infrastructure. China dominates open-source adoption, physical-world AI applications, manufacturing integration, and energy resources for compute scaling.

Xiaomeng Lu, director of Geo-technology at the Eurasia Group political risk consultancy, predicts that 2026 will see both nations dominating distinct niches rather than one achieving comprehensive superiority. “The US has a definite lead in AI chips, though China is catching up in LLM, and is poised to get ahead in certain AI governance areas,” she noted. This bifurcation extends to investment patterns: American firms focus on software scaling and automation of knowledge work, while Chinese investment flows toward robotics and industrial applications.

The divergence carries profound implications for global development. If AI becomes the defining technology of the 21st century, the “Great Divergence” between early adopters and laggards could exceed the economic splits created by the Industrial Revolution. Countries aligning with the American stack gain access to cutting-edge capabilities but face high costs and political conditions. Those adopting Chinese open-source tools receive accessible, customizable platforms but potentially expose themselves to security vulnerabilities and censorship mechanisms embedded in systems like DeepSeek.

As 2026 progresses, the defining question is not which superpower wins, but whether the world can afford a fragmented AI ecosystem where critical infrastructure runs on incompatible standards. The DeepSeek moment proved that barriers to entry have fallen; the challenge now is ensuring that falling barriers do not lead to a divided digital future.

Quick Facts

- DeepSeek’s January 2025 release demonstrated Chinese AI models could match American performance at significantly lower cost using restricted chips

- US venture capital invested $175 billion in AI during 2025 compared to China’s $6 billion, yet Chinese open-source models now lead global download statistics

- The Trump administration partially lifted export controls in December 2025, allowing Nvidia H200 chip sales to China while blocking more advanced Blackwell and Rubin processors

- China’s “AI Plus” initiative targets embedding artificial intelligence across manufacturing, healthcare, and governance by 2035

- The US maintains approximately 90 percent control of advanced AI chip markets but faces power infrastructure constraints limiting data center expansion

- Alibaba’s Qwen models have recorded 700 million downloads globally, making them the most widely adopted open-weight AI systems

- Chinese firms have ordered over $50 billion worth of Nvidia H200 chips following the partial export control relaxation

- The United Nations Global Dialogue on AI Governance in 2026 represents the first attempt at truly global AI coordination, though US-China-EU divisions persist