Japan’s Strategic Subsidies: Building Resilient Overseas Supply Chains

Japan is embarking on an ambitious new phase of industrial policy, offering substantial subsidies to help its companies expand overseas in sectors deemed critical to economic security. From semiconductors and rare earths to shipbuilding, green energy, and high-value food exports, Tokyo’s goal is to secure supply chains, reduce strategic vulnerabilities, and position Japanese firms at the heart of tomorrow’s global industries. This move comes amid intensifying global competition for resources and technology, as well as mounting geopolitical risks that threaten the stability of international trade.

- Japan’s Strategic Subsidies: Building Resilient Overseas Supply Chains

- Why Is Japan Expanding Subsidies for Overseas Supply Chains?

- Key Sectors Targeted by Japan’s Overseas Subsidies

- How Do Japan’s Subsidies Work? Policy Design and Institutional Support

- Challenges and Criticisms: Can Japan’s Subsidy Strategy Succeed?

- Case Studies: Subsidies in Action

- Broader Implications: Japan’s Role in the Global Economy

- In Summary

At the core of this strategy is a recognition that Japan’s economic future depends not only on domestic innovation, but also on the ability to shape and control key links in global supply chains. The government’s new subsidies are designed to help Japanese companies invest in Southeast Asia, the United States, and other emerging markets, ensuring that the flow of critical goods and technologies remains favorable to Tokyo’s interests.

Why Is Japan Expanding Subsidies for Overseas Supply Chains?

Japan’s decision to subsidize overseas expansion marks a significant evolution in its approach to economic security. Traditionally, government support focused on domestic pilot projects or onshoring. However, recent disruptions—such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, and escalating US-China tensions—have exposed the fragility of global supply chains and the risks of overreliance on single countries or regions.

According to the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), the new policy aims to help Japanese companies diversify their production and sourcing, especially in industries where supply disruptions could have severe economic or security consequences. Semiconductors, rare earths, batteries, and shipbuilding are at the top of the list, but the scope also includes green hydrogen, ammonia, and high-value agricultural products.

As reported by Nikkei Asia and Agenzia Nova, the government plans to amend the Economic Security Law to make these initiatives eligible for multi-year subsidies, covering everything from research and development to commercialization. The Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) is expected to play a key role in financing these projects.

Geopolitical Drivers: US-China Rivalry and Supply Chain Risks

Japan’s new subsidies are a direct response to the shifting geopolitical landscape. The US has imposed tariffs and export controls to limit China’s access to advanced technology, while China is investing heavily in infrastructure and supply chains across developing countries. Japan, caught between its largest trading partner (China) and its key security ally (the US), is seeking to hedge its bets by building more resilient and diversified supply chains.

As noted by the East Asia Forum, the Economic Security Promotion Act of 2022 recognized the urgent need for stable semiconductor supplies and domestic industry strength. The new overseas subsidy push is a logical extension, aiming to ensure that Japan is not left vulnerable to external shocks or political pressure.

Key Sectors Targeted by Japan’s Overseas Subsidies

Japan’s subsidy programs are not limited to a single industry. Instead, they target a range of sectors that are vital to both economic growth and national security.

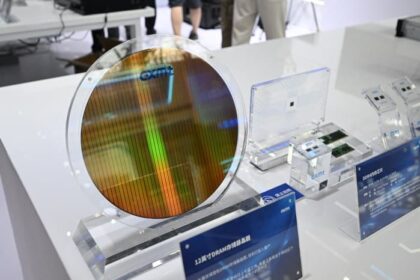

Semiconductors: The Heart of Modern Technology

Semiconductors are the backbone of everything from smartphones and cars to defense systems and artificial intelligence. Japan once dominated this industry in the 1980s, but has since lost ground to Taiwan, South Korea, and the US. Now, Tokyo is investing heavily to regain a foothold, with over $25 billion spent on semiconductor subsidies as of September 2024.

The government-backed Rapidus coalition aims to produce cutting-edge 2nm AI-enabled chips by 2027, while also training thousands of engineers and establishing automated production facilities. Japan’s strategy involves both onshoring (bringing production back home) and offshoring (expanding abroad), particularly in Southeast Asia where labor costs are lower and markets are growing.

However, as the East Asia Forum analysis points out, Japan faces stiff competition from the US and China, both of which are pouring even larger sums into their own semiconductor industries. There are also concerns about a looming shortage of skilled engineers, with estimates suggesting a gap of 40,000 semiconductor professionals in Japan alone.

Global events have underscored the stakes: in 2021, chip shortages cost the automotive industry over $200 million. The US, Netherlands, and Japan have coordinated export controls to restrict China’s access to key chipmaking equipment, making supply chain resilience a top priority for all advanced economies.

Green Energy: Hydrogen, Ammonia, and Decarbonization

Japan’s green transformation is another pillar of its overseas subsidy strategy. The government has launched a multi-pronged support package to unlock $1 trillion in low-carbon infrastructure investment over the next decade, aiming for a 46% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2050.

A significant portion of this funding—about $60 billion—is earmarked for building clean hydrogen and ammonia value chains, both domestically and overseas. The Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (ANRE) has introduced the Supply Chain Subsidy, targeting producers, traders, and self-consumers of hydrogen and ammonia. The goal is to ensure that clean energy can be sold at prices competitive with liquefied natural gas (LNG) and coal, with subsidies covering the difference.

Japan aims to utilize 12 million tonnes of hydrogen by 2040 and introduce 15GW of electrolysers worldwide by 2030. The program is designed to last 15 years for first movers, with periodic reviews and possible extensions. However, challenges remain, including uncertainty over eligibility criteria, financing costs, and the evolving definition of “clean” hydrogen and ammonia.

Food and Agriculture: Exporting Japanese Quality

Japan’s push to expand overseas supply chains is not limited to high-tech sectors. The government is also supporting the export of high-value agricultural and seafood products, aiming to increase export value to 2 trillion yen by 2025 and 5 trillion yen by 2030.

One concrete example is Wismettac Foods, which was selected as a subsidy recipient under the “Emergency Measures for Strengthening Supply Chain Connectivity” in 2024. The company is building logistics and distribution networks to deliver premium Japanese fruits and seafood to the US market, overcoming challenges such as regulatory restrictions and the need to maintain freshness over long distances.

Similarly, Japanese rice exports have surged, driven by a global boom in Japanese cuisine and the yen’s depreciation, which makes exports more competitive. Specialized subsidies for rice exports ensure that certain crops are grown exclusively for international markets, with strict rules preventing diversion to domestic sales. This has helped Japanese food brands like Sushiro and Omusubi Gonbei expand rapidly overseas, serving high-quality rice and sushi to a growing global customer base.

How Do Japan’s Subsidies Work? Policy Design and Institutional Support

The design of Japan’s subsidy programs reflects lessons learned from both domestic and international experience. Subsidies are structured to reduce risks for private companies, encourage investment in critical sectors, and support the development of new business models for overseas markets.

According to a 2024 JBIC survey, Japanese manufacturers are increasingly reviewing their supply chains in response to economic and geopolitical uncertainties. Many are moving operations out of China or expanding sourcing within China to reduce costs and meet market demand. About 90% of surveyed companies are pursuing business transformation, with over 30% doing so through mergers, acquisitions, or collaborations with overseas entities, especially in the US, China, and ASEAN countries.

Efforts toward decarbonization and the circular economy are progressing, with 65% of companies working on energy-saving products and 45% on recycling. However, overseas efforts are often limited by cost and lack of subsidies, underscoring the importance of government support in leveling the playing field.

Legal and Institutional Frameworks: Beyond Subsidies

Experts at the Japan Institute of International Affairs argue that strong domestic legal frameworks and transparent governance are just as important as financial subsidies. Countries with robust institutions attract more investment in industries with complex supply chains, especially those involving sensitive technologies.

“Securing supply chains should focus on institutional development, such as legal frameworks, cybersecurity, and economic intelligence, rather than relying solely on government subsidies,” the JIIA commentary notes.

Japan faces challenges in strengthening cybersecurity, raising economic security awareness among small and medium-sized enterprises, and advancing international regulatory cooperation. Expanding shared regulatory frameworks increases supply chain resilience, but growing protectionism and inward-looking policies in major economies pose risks.

Challenges and Criticisms: Can Japan’s Subsidy Strategy Succeed?

While Japan’s overseas subsidy push is bold, it is not without risks and critics. Some economists warn that subsidy races can lead to inefficiencies, waste government resources, and distort market competition. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have both cautioned that tit-for-tat industrial policies could undermine the rules-based trading system and magnify negative international spillovers.

Japan’s semiconductor subsidies, for example, are large by historical standards—amounting to 0.71% of GDP between 2021 and 2023—but still smaller than the US CHIPS and Science Act ($52.7 billion) or China’s estimated $150 billion in state-led support. There is also a risk that companies will become dependent on government aid, demanding further support to maintain technological leadership in a rapidly evolving industry.

Another challenge is the global shortage of skilled labor, particularly in high-tech sectors. Japan’s labor markets are mobilizing, but the expected shortfall of engineers could limit the effectiveness of subsidy-driven expansion.

Finally, Japan must balance its desire to diversify supply chains away from China with the reality that China remains its largest trading partner and the world’s biggest consumer of semiconductors. Complete decoupling is neither feasible nor desirable, and Tokyo has emphasized the importance of cooperation with both China and South Korea to avoid supply chain disruptions.

Case Studies: Subsidies in Action

Several real-world examples illustrate how Japan’s overseas subsidy strategy is playing out:

- Wismettac Foods: Leveraging government support to build a supply chain for premium Japanese fruits and seafood in the US, overcoming logistical and regulatory hurdles.

- Hyakusho Ichiba: A trading house that has increased rice exports fiftyfold in eight years, thanks in part to export-specific subsidies and the global popularity of Japanese cuisine.

- Semiconductor Expansion: The Rapidus coalition and other public-private partnerships are investing in advanced chip production both in Japan and abroad, aiming to capture a share of the projected $1 trillion global semiconductor market by 2030.

- Green Hydrogen and Ammonia: Japan’s Supply Chain Subsidy program is supporting the development of clean energy value chains, with a focus on international collaboration and long-term market transformation.

These cases demonstrate the breadth of Japan’s approach, spanning traditional industries, advanced technology, and green innovation.

Broader Implications: Japan’s Role in the Global Economy

Japan’s overseas subsidy strategy has far-reaching implications for the global economy, international trade, and the future of industrial policy. By supporting its companies to expand abroad, Japan is not only seeking to secure its own economic interests, but also to shape the rules and standards of tomorrow’s supply chains.

This approach reflects a broader shift among advanced economies toward public-private partnerships, strategic investment, and a move away from pure laissez-faire competition. As the world becomes more interconnected—and more vulnerable to shocks—countries are increasingly focused on resilience, security, and the ability to adapt to rapid technological change.

Japan’s leadership in upholding a rules-based international order, advancing regulatory convergence, and promoting high-standard trade agreements like the CPTPP will be crucial in navigating the challenges ahead. At the same time, Tokyo must ensure that its subsidy programs are well-targeted, temporary, and designed to foster genuine innovation rather than entrenching inefficiency or protectionism.

In Summary

- Japan is expanding subsidies to help companies in critical industries—such as semiconductors, rare earths, green energy, and food—build overseas supply chains and reduce strategic vulnerabilities.

- The new policy is driven by geopolitical risks, global supply chain disruptions, and the need to compete with US and Chinese industrial strategies.

- Subsidies are structured to support research, development, commercialization, and logistics, with a focus on Southeast Asia, the US, and other emerging markets.

- Key sectors include advanced semiconductors, clean hydrogen and ammonia, and high-value agricultural exports.

- Japan’s approach combines financial support with institutional reforms, emphasizing legal frameworks, cybersecurity, and international regulatory cooperation.

- Challenges include global competition, potential inefficiencies from subsidy races, labor shortages, and the need to balance ties with both China and the US.

- Real-world examples, such as Wismettac Foods and the Rapidus semiconductor initiative, illustrate the policy in action.

- Japan’s strategy reflects a global trend toward industrial policy and supply chain resilience, with significant implications for the future of international trade and economic security.