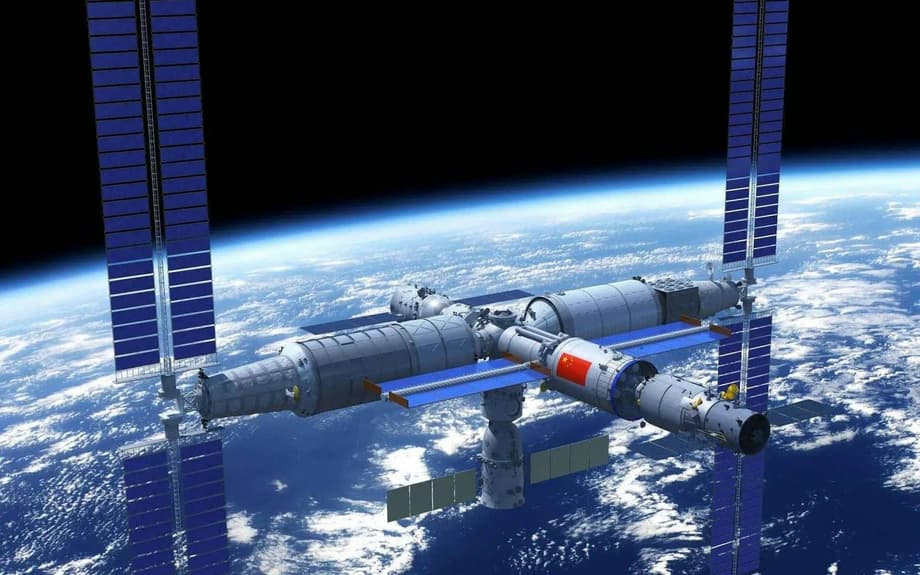

A simple test in orbit points to self-sufficient spaceflight

China has claimed a first in space resource production. Aboard the Tiangong space station, the Shenzhou-19 crew used a compact artificial photosynthesis unit to turn carbon dioxide and water into two essentials, breathable oxygen and ethylene, a hydrocarbon that can feed rocket propellant production. The demonstration, completed through 12 controlled runs inside a drawer shaped device, shows that the core chemistry plants perform on Earth can be engineered to work in orbit.

What makes the result stand out is not just what came out, but the conditions under which it happened. The system operated at room temperature and standard pressure, rather than the extreme conditions many chemical plants require. In microgravity, the astronauts also managed precise control of gas and liquid movement, which is a known challenge when bubbles do not rise and liquids do not settle. The team recorded products in real time, confirming both oxygen generation and hydrocarbon formation.

The technology has been under development in China since 2015. Seeing it function in space is a milestone for any plan that aims to support crews without constant resupply. If spacecraft can make air and fuel where they fly, missions grow lighter, safer, and more flexible. The same toolkit could extend to outposts on the Moon or Mars, where water and carbon dioxide are present in frozen or atmospheric form.

Officials have said the system can be tuned by swapping catalysts to make different products, including methane and formic acid. Methane is already a favored rocket fuel, while formic acid can serve as a building block for more complex chemistry, including steps toward sugar synthesis for food production research. The flexibility points to a future in which one box handles several jobs, from life support to propulsion supply.

How the system works

Artificial photosynthesis copies the logic of plants, but it uses engineered materials rather than leaves. In simple terms, there are two halves to the process. One half splits water into oxygen, sending O2 to the cabin. The other half takes carbon dioxide and adds electrons and hydrogen to build molecules such as ethylene, methane, or formate. Energy comes from sunlight converted by a solar panel, or from light that directly activates a semiconductor catalyst inside the device.

The chemistry in plain language

Inside the Tiangong unit, a semiconductor catalyst provides a surface where carbon dioxide and water interact. When energy arrives, the catalyst helps rearrange atoms. Water gives up oxygen and hydrogen. Carbon dioxide supplies carbon. Depending on the catalyst, the carbon atoms couple in different ways. Copper based catalysts tend to stitch carbons together to form ethylene. Other materials favor methane or carbon monoxide. Engineers choose the catalyst to get the mix they want.

The unit that flew on Tiangong appears to use room temperature pathways that do not need high pressure tanks or elevated temperatures. That reduces the power budget, which is essential on a spacecraft that manages every watt. It also makes the device easier to integrate with air management systems, since oxygen can flow at cabin pressure and hydrocarbons can be stored or routed to processing without heavy duty compressors.

What the Tiangong crew actually did

The Shenzhou-19 crew, which began its mission in late October 2024, ran 12 experiments inside a drawer shaped module. The device housed the catalysts, fluid channels, and sensors needed to manage a three phase reaction with gas, liquid, and solid components. The team verified oxygen production and measured the appearance of ethylene, a key target product for propulsion research.

A central challenge was fluid control in microgravity. On Earth, gases and liquids separate naturally. In orbit, surface tension dominates. The Tiangong hardware included channels, membranes, and flow controls that kept reactants in contact with the catalyst while moving products away so the reaction could continue. The experiment recorded gas movement and separation behavior to guide future designs.

Why microgravity handling matters

If bubbles stick to a catalyst, output falls. If liquids do not reach the reaction surface evenly, hot spots or dry patches form. Precise flow control is the difference between a laboratory proof and a product stream that can feed a storage tank. The data gathered on Tiangong gives engineers the maps they need to scale up the process.

The trial adds to a growing list of space station tests that probe how everyday processes behave without gravity. Past work on Tiangong has included growing lettuce and tomatoes, and even lighting a match to study flame behavior. These studies build the practical knowledge needed to run factories and farms beyond Earth.

Why this matters for life support and propulsion

Every kilogram that does not leave Earth on a rocket saves cost and risk. Oxygen is a prime example. The International Space Station makes oxygen by splitting water in an electrolysis unit powered by solar arrays. Research has estimated that oxygen generation takes roughly one third of the energy budget of the station life support. The approach works, yet the power cost is high and the system still relies on periodic resupply of water and consumables.

Artificial photosynthesis opens a second path. It can convert the carbon dioxide that astronauts exhale back into oxygen, while in the same box it can build hydrocarbon molecules for fuel. The reactions can run at room temperature and cabin pressure, which lowers electrical demand. A station or base that makes its own oxygen and propellants can stretch resupply intervals and reserve more power for science and operations.

There is also value in the menu of products. Methane pairs with liquid oxygen in many modern engines, including designs that aim for reuse. Formic acid can store hydrogen chemically for later use. Ethylene can be burned directly or refined into other fuels and materials. A system that turns waste carbon into useful molecules raises the usefulness of every liter of water and every watt of sunlight aboard a station.

Can ethylene fuel real spacecraft

Ethylene is a simple hydrocarbon with two carbon atoms. It burns readily with liquid oxygen and can serve as a fuel in engines or thrusters. It has been used in research engines and test flights. Performance depends on engine design, but it sits in the same family as methane and propane. The advantage in orbit is that ethylene can emerge directly from carbon dioxide reduction when a copper based catalyst is used.

There are tradeoffs. Ethylene is gaseous at room temperature, so storage requires compression or chilling. Many missions prefer methane because it is easier to handle at cryogenic temperatures alongside liquid oxygen. Ethylene can also be a feedstock. With added processing, it can be converted to liquids or to plastics that are useful for manufacturing. The Tiangong experiment showed the team can hit ethylene as a target, but future missions may retune the catalyst toward methane or formate depending on the application.

Propellant choice is only part of the story. Oxygen is the heavy side of the propellant stack for almost all chemical rockets. Any device that makes oxygen cheaply in space reduces the mass that must be launched. Even if the hydrocarbon side is shipped from Earth at first, a station that supplies oxygen locally will change mission math in a favorable way.

From the space station to the Moon

China has set public targets for a crewed lunar landing before 2030 and for an International Lunar Research Station in the early to mid 2030s. Reports in 2024 described plans to use robots to assemble a compact nuclear reactor to power that base. Power is one piece. The next is a flow of air and fuel that does not depend on cargo flights. The Tiangong trial is presented as a foundation for that goal.

A future orbital supply chain

Another element is the ability to move and share propellant in orbit. In January 2025, China launched the Shijian 25 satellite to test refueling technologies. Paired with production aboard a station, refueling tests point to a supply chain where one platform makes fuel components and another distributes them to satellites or transfer vehicles. A practical setup could look like this. A crewed or robotic platform uses artificial photosynthesis to turn CO2 and water into oxygen and methane. Tanker satellites rendezvous to collect and deliver propellant to spacecraft that need a boost. On the lunar surface, a similar unit feeds oxygen to habitats and stores methane for launch back to orbit. Each location uses local sunlight or nuclear power to run the chemistry.

What needs to happen next

The Tiangong device is a proof of concept, not yet a factory. To support a crew or refuel vehicles, output must increase by orders of magnitude. That requires larger reaction areas, better heat management, and catalysts that last for months without fouling. Space radiation and temperature swings can degrade materials. Engineers will need to test longevity and replace parts without sending up bulky hardware.

Separation and storage are equally hard. Oxygen must be delivered at high purity for breathing and for engines. Hydrocarbons must be separated from byproducts and compressed or liquefied safely. Handling oxygen and fuels inside a spacecraft raises fire risks that designers must reduce with valves, sensors, and strict isolation. None of those challenges are showstoppers, yet they demand careful engineering and repeated testing.

Integration with life support loops will determine real gains. On the ISS, electrolysis pairs with a reactor that combines CO2 and hydrogen to form water and methane, closing part of the loop. A future station could choose between pathways or mix them. The best design may capture CO2 from the air, make oxygen continuously, and route fuel outputs to storage during periods of surplus power. Robotic operation will be essential for routine use.

How this fits into global efforts

Resource production beyond Earth is a shared focus across space agencies. NASA flew the MOXIE experiment on the Perseverance rover to extract oxygen from the Martian atmosphere, proving that a small unit could make oxygen on Mars. The European Space Agency and many labs study photocatalysts that can convert CO2 using sunlight or electricity. Private companies design methane engines to pair with oxygen made on site. These projects share the same idea, use local materials, save launch mass.

Until now, most orbital life support tests have emphasized plant growth, biology, and electrolysis. The Tiangong run is the first report of a carbon dioxide reduction system making a hydrocarbon and oxygen in orbit at room temperature and standard pressure. That step blends life support with propulsion supply inside one box. It raises the bar for what future platforms will try, whether in low Earth orbit, cislunar space, or on the lunar surface.

Competition can speed progress. With plans for a lunar base and deep space missions, China will want to scale the technology. The United States, Europe, Japan, and others have active in situ resource programs and may fly their own demonstrations soon. For engineers, the prize is practical gear that works for months without a fuss.

Key Points

- Shenzhou-19 astronauts ran 12 artificial photosynthesis experiments on Tiangong.

- The device converted CO2 and water into oxygen and ethylene at room temperature and standard pressure.

- Microgravity fluid control and real time detection were validated during the runs.

- By changing catalysts, the system can target methane or formic acid for different uses.

- Compared with water electrolysis on the ISS, the method aims for lower power demand.

- Ethylene can serve as propellant or as feedstock to make other fuels and materials.

- China is pairing in orbit production with refueling tests and planning for a crewed Moon landing before 2030.

- Key challenges ahead include scaling output, long duration stability, and safe storage and handling.