A Nation Split in Two

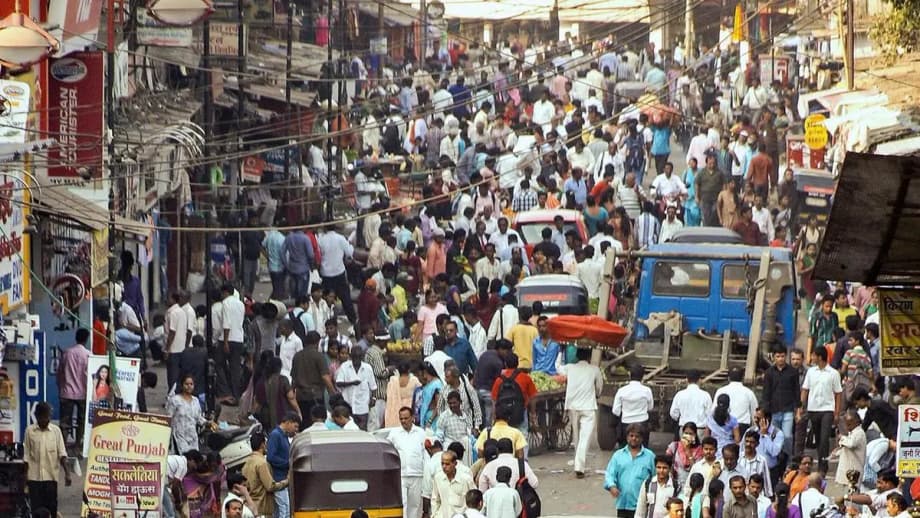

India stands at a critical demographic juncture, a moment where the celebrated narrative of a unified “demographic dividend” is fracturing into a complex story of regional divergence. A new report by the International Institute of Migration and Development (IIMAD) and the Population Foundation of India (PFI) reveals that the country is no longer moving along a single population trajectory. Instead, the nation is witnessing a profound split between a youthful, rapidly growing north and an aging, stabilizing south. This demographic divide carries far-reaching implications for the economy, political representation, and the very fabric of Indian federalism.

The report, titled “Unravelling India’s Demographic Future: Population Projections for States and Union Territories, 2021-2051,” utilizes the Cohort-component method to project that India’s population will rise from 1.35 billion in 2021 to approximately 1.59 billion by 2051. While this growth confirms that India will remain the world’s most populous nation, the annual growth rate is slowing to a modest 0.5 percent. This deceleration effectively marks the end of the era of “population explosion” paranoia that dominated political and academic discourse for decades. However, the stabilisation of India’s population, a target originally set for 2045 under the National Population Policy 2000, now appears out of reach and is likely to take an additional two decades.

Contrasting Trajectories

The most striking revelation in the data is the sharp contrast between the Hindi-speaking heartland and the southern states. States in the north and central regions, including Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh, are projected to record average annual population growth rates significantly higher than the national average. Bihar leads with a projected growth rate of 1.1 percent, followed by Uttar Pradesh at 0.9 percent. These states will contribute the lion’s share of the overall population increase in the coming decades.

In contrast, the southern states—Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana—are expected to record growth rates well below the national average. These regions have largely completed their fertility transition and are approaching a stage of population stabilisation characterized by near-zero growth. By the middle of the century, the southern region’s share of the national population is projected to fall from 20 percent to 17 percent. Conversely, the combined share of the northern and central regions will rise from 48.6 percent to a projected 52.7 percent, effectively shifting the center of India’s demographic gravity northward.

“India has a fantastic window of opportunity but it will only be there for approximately the next two decades,” said Poonam Muttreja, the executive director of Population Foundation India. “We have the capacity to tap into the potential of the youth population but we need to invest in adolescent education, health and sexual health right away if we want to reap the benefits.”

The Age Gap Emerges

This divergence in growth rates is creating a generational gap between the regions. By 2036, the average Tamil man is projected to be over 12 years older than the average Bihari man. While Kerala achieved replacement fertility (a rate of 2.1 children per woman) back in 1998, Bihar is not expected to reach that milestone until 2039. This means that while the south grapples with the challenges of an aging society, the north will continue to possess a “youth bulge.” In 2011, India’s population pyramid had a classic youthful shape, wide at the base. By 2051, the national pyramid is expected to become more rectangular, reflecting a balanced but progressively older age composition. However, this national average hides the reality that the north will remain bottom-heavy while the south becomes top-heavy with elderly citizens.

The Political Battle for Representation

The demographic asymmetry is fueling a high-stakes political crisis ahead of the 2026 delimitation exercise, the process of redrawing parliamentary constituencies based on population data. India’s Constitution mandates that seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament, be allocated to states based on their population. However, to incentivize population control, the allocation of seats has been frozen based on the 1971 census figures. This freeze is set to expire after the census due in 2026, raising fears in the south that their political influence will be drastically diminished.

Projections indicate a significant power shift if delimitation is based purely on current population figures. Northern states such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh are expected to gain seats, while southern states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh stand to lose representation. Estimates suggest the north could gain as many as 43 seats while the south loses 24. For southern leaders, this represents a penalty for successfully implementing family planning and development policies. MK Stalin, the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, has described the situation as a “Damocles’ sword hanging over southern India.”

Southern states argue that they contribute disproportionately to the national GDP and tax revenues. For instance, Tamil Nadu contributes roughly 8.4 percent to India’s GDP while having only 6.5 percent of the population. Reducing their parliamentary representation based solely on population, they contend, is unfair and undermines the concept of “cooperative federalism.” Conversely, northern leaders argue that the democratic principle of “one person, one vote” necessitates increased representation for their larger populations, which also face greater infrastructure and development needs.

Economic Implications and Labor Mobility

The demographic divide is reshaping India’s economic landscape, particularly regarding labor markets and internal migration. As the south’s working-age population shrinks and ages, the region faces a potential labor vacuum. Conversely, the north has a surplus of young workers entering the job market. This dynamic is driving a new trend of southward migration, where workers from states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh move to southern economic hubs such as Bengaluru, Chennai, and Hyderabad.

This movement, often termed “replacement migration,” is viewed by some economists as a necessary mechanism to balance the country’s demographic mismatch. Migrants can fill labor shortages in the south, contribute to the local economy, and send remittances back to their home states in the north. However, this influx has also triggered nativist sentiment and political rhetoric in some southern states, where locals fear competition for jobs and resources. States like Karnataka have even considered legislation to reserve jobs for locals, though such measures face legal and constitutional challenges.

The shifting demographics are also altering India’s migration patterns to the rest of the world. Historically, the southern state of Kerala was a major source of labor for the Gulf countries. As Kerala’s working-age population declines, the flow of migrants to the Gulf is shifting northward. Data shows a sharp decline in the number of emigration clearances issued to workers from Kerala and Tamil Nadu, while northern states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar now account for a significant and growing share of the workforce heading to West Asia. This shift has implications for remittances, which remain a vital source of income for many Indian states.

Challenges in Education and Employment

The demographic transition is already leaving visible marks on India’s education system. As fertility rates decline, the number of school-aged children is dropping, leading to reduced enrolment. Data from the Unified District Information System for Education (UDISE+) shows a sharp dip in enrolment from pre-primary to class 12, with a decrease of 13.4 million students between 2018-19 and 2024-25. This decline has forced the closure or merging of approximately 80,000 schools across the country, including 70,000 government schools.

The impact of this enrolment drop is geographically uneven. Southern states, with fewer children, are seeing the closure of “uneconomic” schools. Meanwhile, parents in northern states, despite having fewer children than previous generations, are increasingly shifting students from government to private schools, driven by a desire for better quality education. This trend highlights the need for the government to adapt its educational infrastructure, potentially repurposing school facilities in the south for other uses such as vocational training or elderly care, while improving the quality of public education in the north to manage the demand.

Employment remains the most critical challenge. India’s working-age population (15-59 years) is projected to peak at 1.01 billion in 2041. To harness this demographic dividend, the economy must create millions of new jobs annually. However, current data shows high youth unemployment and a skills mismatch. The World Economic Forum reports that only 20 percent of India’s workforce is skilled, compared to a global average of 80 percent in developed countries. Without urgent investment in skill development and structural economic reforms to boost labor-intensive manufacturing, the country risks turning its demographic dividend into a demographic disaster, where a large population of unemployed youth leads to social unrest.

What to Know

- India’s population is projected to grow from 1.36 billion in 2021 to 1.59 billion by 2051, with a slowing growth rate of 0.5 percent.

- A sharp demographic divide exists between the northern states (high growth, youthful) and southern states (low growth, ageing).

- Bihar and Uttar Pradesh will account for a significant portion of the population increase, while Kerala and Tamil Nadu face stabilization and decline.

- The 2026 delimitation exercise threatens to reduce the political representation of southern states while increasing the power of the north.

- School enrolment has dropped by 13.4 million since 2018, leading to the closure of tens of thousands of schools.

- Internal migration patterns are shifting southward to address labor shortages in ageing southern economies.

- India’s demographic dividend window is expected to peak around 2041, requiring immediate focus on job creation and skill development.