The Ancient Network That Connected Civilizations

For over a millennium, the Silk Road served as the world’s largest network of trade routes, connecting the empires of Han China in the East with the Roman Empire in the West. This complex web of land and sea routes facilitated not only the exchange of goods but also the movement of ideas, religions, and technologies that shaped human history. While often thought of as a single road, the Silk Road was actually a network of routes spanning over 6,000 kilometers across Central Asia. At the heart of this vast network stood ten extraordinary cities, each serving as crucial hubs where merchants rested, traded, and exchanged far more than just commodities.

- The Ancient Network That Connected Civilizations

- Eastern Hubs: Where the Silk Road Began

- Central Asian Powerhouses: The Heart of the Trade Network

- Western Trade Centers: Where East Meets Mediterranean

- The Terminal Cities: Where the Silk Road Ended

- Enduring Legacy: From Ancient Trade Routes to Modern Connections

- The Essentials: What to Know About Silk Road Cities

These urban centers grew into some of the largest and most sophisticated cities of their time, attracting diverse populations from across Eurasia. Their importance extended beyond mere trade – they became melting pots where different cultures, religions, and artistic traditions met and merged. From Chang’an’s million inhabitants to Merv’s thriving Islamic center, these cities represented the pinnacle of urban development in their respective eras. Understanding their history, location, and significance offers a window into how ancient globalization worked and how it continues to influence our world today.

Eastern Hubs: Where the Silk Road Began

The Silk Road journey through China began with magnificent cities that served as departure points for merchants heading west. These eastern hubs not only processed goods but also played crucial roles in cultural exchange, particularly in the transmission of Buddhism along the trade routes.

Chang’an: The Million-Person Metropolis

With more than a million inhabitants at its height, Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) stood among the largest cities in the world during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). As the capital of imperial China, this magnificent metropolis served as the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, where goods from across Asia and beyond converged. Chang’an’s urban planning reflected its importance as an international center, with two distinct markets serving different functions.

The Eastern Market catered specifically to the imperial household and aristocrats, offering luxury goods and specialized products. Meanwhile, the Western Market served the general population and became renowned for its foreign imports – a true international bazaar where merchants from Persia, India, and Central Asia sold exotic goods. This market featured jewelry, silk, tea, rare medicines, and spices that quickly shaped local tastes and fashion trends. Chang’an’s cosmopolitan nature attracted foreigners from across Eurasia, making it a true melting pot of cultures where diplomatic missions, religious pilgrims, and merchants mingled.

The sheer scale and diversity of Chang’an’s markets made it the most important urban center in East Asia and a gateway between Chinese civilization and the wider world.

Dunhuang: The Desert Gateway to Buddhist East

For over a thousand years, Dunhuang served as a pivotal hub for commerce, culture, and military activity at the western end of China’s Hexi Corridor. After Emperor Wu’s forces defeated the Xiongnu in 121 BCE, Dunhuang became a strategic center despite its harsh desert environment. The city’s importance grew as it evolved into one of the first major gateways through which Buddhism entered China from Central Asia.

The monk Lezun excavated the first Mogao Grotto at Dunhuang, beginning a tradition that would eventually create one of the world’s most significant Buddhist art complexes. By the Tang Dynasty, Dunhuang had become a thriving center where Buddhist scriptures were translated and studied. Archaeological discoveries at Dunhuang have yielded remarkable finds, including the earliest dated printed book ever discovered – the Diamond Sutra from 868 CE. This Buddhist text, discovered in 1907, represents one of the most significant archaeological finds from the Silk Road era and demonstrates the city’s crucial role in both material trade and the spread of religious ideas.

Kashgar: China’s Wild West Caravan Junction

Often described as China’s “Wild West,” Kashgar long served as the crucial interface between Central Asia and China. This oasis city became an assembly point for caravans about to embark on the perilous journey across the Taklamakan Desert, forcing merchants to choose between northern and southern routes around the desert’s rim. According to historical accounts, Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty sought the region’s legendary “blood-sweating” heavenly horses for his armies, which opened the way beyond the desert frontier.

Chinese control over Kashgar remained intermittent throughout two millennia of history, with the Uyghur minority maintaining their position as the local majority. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Kashgar found itself at the center of the “Great Game” – the strategic rivalry between the British and Russian empires for influence in Central Asia. Diplomats, intelligence agents, archaeologists, and explorers crowded the city’s bazaars, creating a fascinating crossroads where languages, interests, and ambitions all overlapped. Kashgar’s Old City with its traditional bazaars and caravan yards continues to preserve the atmosphere of this vibrant Silk Road trading hub.

Central Asian Powerhouses: The Heart of the Trade Network

Stretching across the vast expanse of Central Asia lay the true heart of the Silk Road network, where the most significant urban centers flourished. These cities became wealthy not just through trade but also through their role as cultural and intellectual crossroads where different civilizations met and interacted.

Samarkand: The Sogdian Merchant Capital

Situated at the western tip of the Alai Mountains in modern-day Uzbekistan, Samarkand represents one of the most iconic Silk Road cities. Founded around 2,750 years ago, Samarkand experienced numerous conquests – by Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and Timur (Tamerlane) – yet somehow managed to maintain its commercial significance throughout these upheavals. Between the 6th and 8th centuries, Samarkand served as the capital of the Sogdians, who organized much of the transcontinental luxury trade that enriched Tang China.

The Sogdians created Asia’s largest trading empire during this period, establishing vast commercial networks that extended from China to the Mediterranean. Their success stemmed from several key advantages: mastery of multiple languages that facilitated trade across diverse regions, religious openness (many were Zoroastrian but receptive to Buddhism, Christianity, and Manichaeism), and remarkable adaptability to changing political conditions. Samarkand’s Registan Square, framed by three exquisite madrassas, remains one of the most breathtaking examples of Islamic architecture and a testament to the city’s enduring cultural significance.

Balkh: The Mother of Cities

Known as the “Mother of Cities,” Balkh stood as one of the most significant urban centers in ancient Bactria, located approximately 22 kilometers west of modern-day Mazar-i-Sharif in Afghanistan. This remarkable city served as a hub for trade and diverse religious traditions throughout its long history. Alexander the Great fought in this region and married Roxanne, the local princess, shortly after his conquest. During the early 7th century, the renowned Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang documented the presence of numerous Buddhist communities in Balkh, indicating its importance as a center of Buddhist scholarship.

Balkh’s religious significance extended beyond Buddhism – it was also considered the birthplace of Zoroaster, the founder of Zoroastrianism. Some traditions hold that the prophet died here, while others suggest he was born in this influential city. Centuries later, Balkh gained further prominence as the birthplace of the great Sufi poet Rumi. In 1220, Genghis Khan’s forces devastated the city during their westward expansion, destroying much of its urban fabric. Despite this destruction, Balkh remains an archaeological treasure trove with layers of history reflecting its importance across millennia.

Merv: The Islamic Cultural Center

Located east of Mary in Turkmenistan’s Karakum Desert, Merv stands as one of Central Asia’s most important historical sites and one of the largest medieval cities ever discovered. By the 12th century, Merv rivaled Damascus, Baghdad, and Cairo as a major Islamic center under the Seljuk Turks. The city’s layered urban landscape reflected its complex history, with fortresses, palaces, religious buildings, and residential areas built by successive empires including the Parthians, Sassanids, and Seljuks.

Merv’s oldest surviving structure, the El Kekara fortress, dates back to the 6th century BCE, demonstrating the site’s extraordinary longevity as an urban center. The city reached its zenith during the 12th century when it served as the capital of the Great Seljuk Empire. Tragically, in 1218, the Mongols demanded tribute from Merv. After the Mongol envoy was killed, Tolui led an army that in 1221 utterly destroyed the city, massacring its estimated population of 200,000 to 500,000 inhabitants. This devastating event marked the end of Merv’s era as one of the world’s great cities, though its ruins continue to provide invaluable insights into medieval Islamic urban life.

Tugunbulak and Tashbulak: The Newly Discovered Highland Metropolis

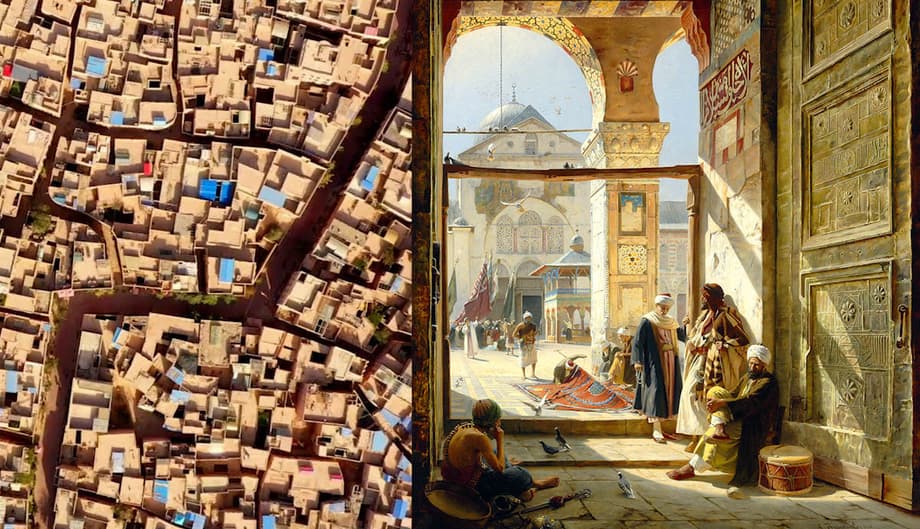

Recent archaeological discoveries are revolutionizing our understanding of Silk Road urban development. Using groundbreaking drone-based lidar technology, researchers have uncovered the remains of medieval cities perched above the ancient Silk Road in the rugged mountains of southeastern Uzbekistan. These discoveries challenge long-held assumptions about urban life in remote mountain regions of Central Asia during the medieval period.

The most significant find is Tugunbulak, a sprawling, high-altitude metropolis that covered nearly 300 acres, making it one of the largest regional settlements of its time. Situated at altitudes reaching up to 7,200 feet (similar to Machu Picchu), this city thrived between the 6th and 11th centuries. The lidar technology revealed an urban landscape featuring five watchtowers linked by walls along ridgelines, a central fortress protected by thick stone and mud-brick walls, and numerous residential and commercial structures. Nearby, the smaller but densely built city of Tashbulak has also been surveyed, showing similar architectural sophistication.

This changes everything we thought we knew about Central Asian history. These weren’t the barbarian horse-riding hordes that history has often painted them as. They were mountain populations, probably with nomadic political systems, but they were also investing in major urban infrastructure.

Michael Frachetti, National Geographic Explorer and Washington University anthropologist

Archaeological evidence suggests these highland urban centers weren’t merely surviving but thriving in ways that defy expectations of medieval mountain societies. The discovery indicates that large urban centers were not uncommon in high-altitude regions, challenging the assumption that such areas remained peripheral to major developments. Researchers believe Tugunbulak’s economy was driven by metalworking industries, particularly iron and steel production, capitalizing on the region’s rich mineral deposits and harnessing strong mountain winds for high-temperature fires needed in smelting operations.

Western Trade Centers: Where East Meets Mediterranean

As the Silk Road continued westward, it passed through a series of crucial cities that served as intermediaries between the world of Central Asia and the Mediterranean basin. These cities adapted Eastern goods for Western markets while simultaneously introducing Middle Eastern and European products to Asian consumers.

Ctesiphon: The Imperial Capital of Parthia and Persia

Ctesiphon, located on the Tigris River southeast of modern-day Baghdad, served as the capital of the Parthian Empire and later the Sassanid Dynasty. This magnificent city witnessed numerous conflicts with Rome, which held it at times during its long history. The Sassanian state made Ctesiphon a seat of power until, in 637 CE, Arab armies captured the city and used it as a base for conquering eastern Persia. Though only ruins remain today – including mud-brick walls and vestiges of palaces – Ctesiphon’s scale remains visible in its most famous surviving structure.

The Taq Kasra, or the vaulted hall of Khosrow I, stands as one of the most remarkable architectural achievements of ancient times. Its unreinforced brick arch rises approximately 100 feet, making it the tallest single-span brick vault in the world. This monumental structure exemplifies the engineering prowess of Persian architecture and served as a symbol of imperial power during Ctesiphon’s peak as a Silk Road hub. The city’s importance as an administrative center and marketplace made it indispensable for the regional redistribution of goods flowing along east-west routes.

Palmyra: Syria’s Pearl of the Desert

Set in an oasis on the edge of the Syrian Desert, Palmyra (modern Tadmur) played a crucial role connecting the Persian Gulf and Asia with the Mediterranean and Europe. From the 1st century CE, this desert settlement grew wealthy as a trading center where merchants brought Chinese silk, pottery, and herbs through Syria in exchange for glass, dyes, and pearls. Often called Syria’s “Pearl of the Desert,” Palmyra experienced rapid expansion under Roman rule, reaching its peak in the 2nd century CE.

Under Queen Zenobia (c. 240-274 CE), Palmyra briefly broke away from Roman control and established the short-lived Palmyrene Empire. When Rome ultimately destroyed Palmyra in 273 CE, it ended the city’s independence, though its ruins continue to impress visitors today. The city’s colonnaded avenues, towering tombs, and temples cover approximately 2.3 square miles, providing a spectacular window into the urban sophistication of this desert trading hub. Archaeological discoveries at Palmyra, including the discovery of catacombs linked to Queen Zenobia in 1957 during oil pipeline construction, continue to reveal the city’s rich history and significance in the Silk Road network.

Damascus: The Silk Processing Center

Damascus sits at the foot of Mount Qasioun, where the Barada River’s tributaries feed gardens and workshops that have sustained urban life for millennia. This ancient city played a specialized role in the Silk Road network – it became the primary center for processing Chinese silk to suit Western markets. By 115 CE, Chinese silk was being finished and dyed in Damascus to meet the demands of Roman consumers before being shipped to Rome or sold locally in the city’s markets.

Several caravanserais have survived near Damascus’s Old City souqs, providing physical evidence of the city’s commercial importance. These structures typically featured animal stables on lower levels and rooms for merchants above, with open courtyards serving as trading floors. This arrangement was once common throughout the Silk Road network and remains visible in Damascus’s traditional architecture and urban layout. The city’s role in adapting Asian silks for Mediterranean markets became so significant that the English word “damask” eventually entered the language as a synonym for fine silk, forever preserving Damascus’s commercial legacy in language and culture.

The Terminal Cities: Where the Silk Road Ended

As the Silk Road approached the Mediterranean world, it terminated in several major cities that served as final destinations for Asian goods and departure points for European distribution. These cities became incredibly wealthy through their control of final trade and distribution networks.

Constantinople: The Imperial Chokepoint

Known in the past as Constantinople, Istanbul has served as the capital of three major empires – the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman – and briefly as the capital of modern Turkey. The city was renamed Constantinople in 330 CE when Emperor Constantine established it as the “New Rome,” and became Istanbul following the Ottoman conquest in 1453. Though the Turkish Republic moved the capital to Ankara in 1923, Istanbul remained the country’s largest city.

Historically, Constantinople functioned as both a commercial hub and an indispensable route for merchant ships from Black Sea ports. Located at the strategic meeting point of Asia and Europe, it often serves as considered the terminus of the Asian overland Silk Road. The city’s wealth came from its ability to control trade between the Black Sea and Mediterranean, allowing it to levy taxes on goods passing through its markets. Its harbors along the Golden Horn served as the final stop for many caravans before their goods were distributed throughout Europe. Constantinople’s magnificent markets, customs houses, and administrative buildings reflected its position at the apex of the Silk Road trade network.

Modern Rediscoveries: Unveiling Lost Silk Road Cities

The quest to understand the Silk Road continues today, with archaeologists making remarkable discoveries that shed new light on this ancient trade network. One of the most significant recent finds involves submerged ruins in Lake Issyk-Kul in eastern Kyrgyzstan. Researchers from the Russian Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Sciences of the Kyrgyz Republic have uncovered traces of an urban complex that includes fired-brick buildings, a possible religious structure, and a necropolis with Islamic-style burials.

These ruins lie at remarkably shallow depths between 3 and 13 feet (1-4 meters) beneath the lake surface, suggesting they were submerged relatively recently in geological terms. The site, known as Toru-Aygyr, appears to have been a significant commercial and cultural node along a key Silk Road route. Researchers believe the city’s demise resulted from a catastrophic earthquake powerful enough to permanently alter the landscape and submerge the settlement. This discovery adds a new dimension to our understanding of Silk Road urban centers, showing that they existed in diverse environments and could disappear through sudden natural disasters.

Similarly, archaeological work in Pakistan’s Kargil region has revealed family collections of Silk Road artifacts that represent some of the finest privately held collections in India. Muzzamil Hussain’s family discovered wooden crates in an old property containing silks from China, silver cookware from Afghanistan, rugs from Persia, turquoise from Tibet, saddles from Mongolia, and luxury goods from London, New York and Munich. This collection has been preserved in the Munshi Aziz Bhat Museum, offering visitors a personal connection to the last-known traders along one of the final sections of the Silk Road to close, following the partition of India and Pakistan in 1948.

Enduring Legacy: From Ancient Trade Routes to Modern Connections

The Silk Road concept continues to influence global connections today. In recent years, China has revived the idea of the Silk Road through the “Belt and Road Initiative,” developing overland and maritime routes to boost connectivity across more than 60 countries. Modern cities seeing major transformation include New Lanzhou, Wuwei, and Khorgas in China; Aktau in Kazakhstan; Gwadar in Pakistan; Anaklia in Georgia; and Rotterdam in the Netherlands, demonstrating the enduring legacy of these ancient trade routes.

UNESCO has recognized the Silk Road’s significance by establishing the Silk Roads Programme, which provides an inventory of major cities along these routes and their importance in cultural exchange. Many of these ancient urban centers have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, including Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva in Uzbekistan, ensuring their preservation for future generations. These sites serve as living museums where visitors can experience the architectural and cultural achievements of Silk Road civilizations.

The concept of the Silk Road also challenges traditional historical narratives that focus exclusively on Western civilization. As historian Peter Frankopan argues in “The Silk Road is once more the centre of the world,” viewing history from the perspective of these trade routes reveals different patterns of cultural exchange and influence. The world’s great religions – Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism – all emerged along or near the Silk Road, making this network not just a conduit for goods but also a crucible of religious and philosophical development.

Furthermore, recent archaeological discoveries continue to reshape our understanding of these ancient cities. The lidar scans of Uzbekistan’s highland cities, the underwater archaeology at Lake Issyk-Kul, and the reevaluation of traditional historical accounts all contribute to a more comprehensive picture of Silk Road urban life. These findings demonstrate that the Silk Road was not merely a network of desert caravans but a complex web of routes that connected mountains, oases, rivers, and seas, supporting diverse forms of urban settlement and commerce.

The Essentials: What to Know About Silk Road Cities

- Chang’an (modern Xi’an) was among the largest cities in the world during the Tang Dynasty with over one million inhabitants, featuring distinct markets for foreign goods and imperial luxury items

- Dunhuang served as both a strategic desert waypoint and early Buddhist gateway to the East, where the earliest dated printed book, the Diamond Sutra, was discovered

- Kashgar long functioned as a caravan junction before merchants chose between north or south routes around the Taklamakan Desert

- Samarkand was the Sogdian merchant capital that organized much of the transcontinental luxury trade enriching Tang China between the 6th and 8th centuries

- Balkh, known as the “Mother of Cities,” connected diverse religious traditions including Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and later Sufism

- Merv rivaled Damascus, Baghdad, and Cairo as a major Islamic center in the 12th century before its destruction by Mongol forces in 1221

- Recent lidar technology has revealed high-altitude Silk Road cities like Tugunbulak that challenge assumptions about medieval mountain societies

- Ctesiphon’s Taq Kasra remains the tallest single-span brick vault in the world, reflecting the engineering achievements of Sassanian architecture

- Damascus specialized in processing Chinese silk to suit Roman markets, leading to the English word “damask” as a synonym for fine silk

- Constantinople (modern Istanbul) served as the final terminus of the Asian overland Silk Road and controlled trade between the Black Sea and Mediterranean