A Breakthrough in Offshore Wind Energy

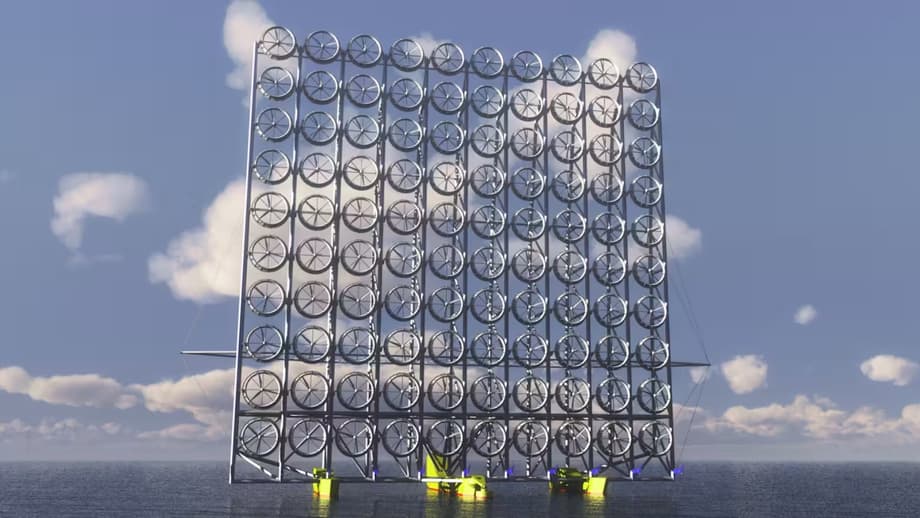

Japanese researchers have developed an innovative wind turbine wall technology that could transform ocean energy production, potentially tripling power output compared to conventional offshore wind turbines. This breakthrough comes from Kyushu University, which has established itself as Japan’s leading institution for wind turbine development through its unique combination of hardware and software capabilities. The university’s Research and Education Center for Offshore Wind (RECOW), established in April 2022, has been at the forefront of designing multiple innovative offshore wind turbine configurations.

- A Breakthrough in Offshore Wind Energy

- Japan’s Urgent Energy Transition Imperative

- Understanding the Wind Turbine Wall Technology

- Global Context for Floating Wind Innovation

- Challenges Facing Japan’s Offshore Wind Sector

- Technical Foundations and Support Innovations

- Broader Japanese Innovations in Renewable Energy

- Supply Chain and Infrastructure Considerations

- International Perspectives and Investment Strategies

- The Path Forward for Japan’s Renewable Energy Leadership

- Key Points

Ju Tanimoto, Executive Vice President and Senior Vice President of Kyushu University, emphasized the institution’s unique position in October 2024 when he said:

Kyushu University is the only university in Japan capable of developing wind turbines, combining its unique wind turbine & floating structure technology (hardware) and wind analysis & fluid structure analysis technology (software).

The development of this wind turbine wall arrives at a critical moment as the world faces a climate crisis and rapidly increasing demand for clean energy solutions. Since 2000, renewable energy sources have grown from accounting for 19% of global electricity to 30% by 2023, with solar power leading the charge. However, wind energy has emerged as another crucial component in the transition away from fossil fuels, particularly for meeting the substantial energy demands of commercial and industrial operations.

The wind energy sector has demonstrated remarkable growth, with an 11% growth rate and total energy capacity reaching 1.2 Terawatts as of late 2024. Offshore wind energy development has gained particular momentum as it allows countries to harness stronger and more consistent winds over open ocean areas.

Japan’s Urgent Energy Transition Imperative

Japan’s pursuit of innovative wind technology reflects a desperate national need for energy transformation. The country faces one of the most challenging energy landscapes among developed nations, with its energy self-sufficiency rate dropping dramatically from 20.2% in 2010 to just 15.2% in 2023, positioning it as the second lowest among the 38 OECD member countries. This decline resulted primarily from the shutdown of nuclear power plants following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and subsequent nuclear accident at Fukushima.

To compensate for lost nuclear capacity, Japan has relied heavily on thermal power generation, which increased from 65.4% of the energy mix in 2010 to 72.8% in 2022—the highest among G7 nations. This heavy dependence on imported fossil fuels, including oil, coal, and liquefied petroleum gas, leaves Japan’s electricity supply vulnerable to external factors including geopolitical risks, resource price fluctuations, and exchange rate shifts.

The Japanese government has recognized this vulnerability and approved the Strategic Energy Plan in February 2025, alongside the GX2040 Vision for decarbonization. These policy frameworks aim to make renewable energy the primary power source while maintaining nuclear power as a supplementary option. Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Muto stated that this plan aims to create a power mix that does not overly rely on any specific energy source or fuel.

Japan has set ambitious targets to increase its energy self-sufficiency rate to 30% by 2030, with plans to expand renewable energy’s share from 20% to 36-38%. Offshore wind power features prominently in this strategy, with targets to increase installed capacity from just 0.15 GW as of March 2024 to 5.7 GW by 2030. The government has secured offshore areas for demonstration tests, with agreements from local fishery associations in waters off Akita Prefecture and off the coast of Toyohashi and Tahara City in Aichi Prefecture.

Understanding the Wind Turbine Wall Technology

The innovative wind turbine wall developed by Kyushu University represents a significant departure from conventional offshore wind designs. While specific technical details remain under development, the concept fundamentally reimagines how wind turbines can be configured to maximize energy capture in offshore environments. This innovation builds upon Japan’s broader efforts to advance floating offshore wind technology, which is particularly suitable for Japan’s geography where the sea depth increases rapidly from the coastline.

Floating wind turbine technology has emerged as a crucial solution for accessing deep-water wind resources where fixed-foundation turbines are not economically feasible. Unlike conventional offshore wind turbines with long towers sunk into the seabed in shallow seas, floating turbines sit in buoyant concrete-and-steel keels that enable them to stand upright on the water, much like a fishing bobber. These structures are held in place with mooring cables attached to anchors on the seafloor.

The primary advantage of floating turbines lies in their ability to access large swaths of outlying ocean waters, up to half a mile deep, where the world’s strongest and most consistent winds blow. Additionally, floating turbines can be installed over the horizon, out of sight of coastal residents, addressing aesthetic concerns that have hindered near-shore wind development in many regions.

Frank Adam, an expert on wind energy technology at the University of Rostock in Germany, emphasized the potential of this technology when he said:

Floating wind power has enormous potential to be a core technology for reaching the climate goals in Europe and around the world.

The ocean space beyond the reach of conventional offshore turbines makes up 80% of the world’s maritime waters, opening vast opportunities for floating arrays. The wind turbine wall technology developed by Kyushu University appears to represent the next evolution of floating offshore wind, potentially offering dramatic improvements in power output efficiency.

Global Context for Floating Wind Innovation

Japan’s wind turbine wall development fits within a broader global movement toward floating offshore wind technology. The first floating wind energy array, Hywind Scotland, began operations with five towering 574-foot-tall turbines located 15 miles offshore. This project, 75% owned by Norwegian firm Equinor, has successfully operated through harsh conditions including Hurricane Ophelia and winter storms with 100 mile-an-hour winds and 27-foot waves.

Walt Musial, an offshore wind energy expert at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, noted that nearly 60% of suitable offshore wind locations in the United States exist at depths greater than 200 feet where conventional offshore wind turbines are not feasible. This creates significant opportunities for floating wind energy technologies, particularly for countries with limited shallow coastal waters.

Po Wen Cheng, head of an international research project on floating wind energy at the University of Stuttgart, suggested that floating turbines could produce more energy than the largest onshore or offshore technologies. He explained that not only are winds in deeper waters more powerful than those closer to shore, but the physics of the flexible, suspended rigs enables them to carry larger turbines.

The bigger the turbine, the more energy they can produce in the right conditions,

said Cheng.

Cheng argued that floating turbines could be even taller than today’s largest offshore rigs, perhaps with 400-foot blades and towers stretching nearly 1,000 feet into the air—as tall as the Eiffel Tower. Turbines of such dimensions could generate three times the electricity of today’s most advanced onshore turbines, aligning with the potential tripling of power output claimed for Japan’s wind turbine wall technology.

The Hywind Tampen floating offshore wind farm, recognized as the world’s largest, began operating in August 2023 with 88MW capacity. Other projects, including the WindFloat Atlantic project in Portugal expected to power 60,000 homes, demonstrate the growing momentum behind floating wind technology.

Challenges Facing Japan’s Offshore Wind Sector

Despite technological innovations like the wind turbine wall, Japan’s offshore wind industry faces significant hurdles. The country’s three auction rounds for offshore wind projects have produced more cautionary tales than turbines. The sole winner of Round 1 withdrew, while Round 2 and Round 3 winners struggle with severe financial challenges. The government even postponed its fourth auction indefinitely in October to reassess the entire framework.

In a shocking development that highlighted these challenges, Mitsubishi Corporation abandoned three massive offshore wind projects in August, paying £20 billion in penalties rather than proceeding. This decision to walk away from 1.7 gigawatts of capacity—enough to power 1.3 million homes—signaled a fundamental crisis in how Japan approaches its offshore wind future.

While Japan aims to reach 10 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity by 2030 and 45 gigawatts by 2040, current installed capacity stands at just 0.3 gigawatts. In stark contrast, China added 8 gigawatts of offshore wind in 2024 alone, while Taiwan, South Korea, and Vietnam race ahead with ambitious buildouts.

Takeshi Matsuki, Global Wind Energy Council’s Japan Country Manager, emphasized the urgency of the situation when he said:

Japan holds vast offshore wind potential and cannot afford to miss its chance to become an offshore wind leader, especially within the Asia-Pacific region.

A white paper from the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) titled Unlocking Japan’s Offshore Wind Potential identifies three critical reform areas needed to address these challenges. The auction framework creates uncertainty through price-focused evaluation criteria that drove developers to submit unrealistically low bids. The revenue structure relies on a Feed-in Premium (FIP) scheme tied to volatile market prices that averaged ¥9-16 per kilowatt-hour in 2025—well below the ¥12-15/kWh needed for early offshore wind projects to be economically viable.

Beyond these structural issues, developers face a complex permitting process, certification requirements that lack transparency, and grid curtailment threats in high-potential regions without compensation mechanisms. These challenges have led developers to warn they were at the brink of whether this business can continue.

Technical Foundations and Support Innovations

While Kyushu University works on the wind turbine wall itself, other Japanese companies are developing crucial supporting technologies for offshore wind installations. Obayashi Corporation has developed an ocean structure called Skirt Suction applied to offshore wind turbine foundations and anchors, addressing one of the most significant challenges in offshore wind construction.

The Skirt Suction technology consists of a top slab and a cylindrical vertical wall (the skirt) leading down from the top slab. It fixes offshore wind turbines more firmly in place than previous foundations by having the skirt penetrate the seabed foundation. This installation method does not require large machinery like pile drivers, potentially reducing construction costs by approximately 20% and shortening the construction period by approximately 40%.

Experiments in sea areas with sandy soil common around Japan demonstrated that Skirt Suction provides approximately three times as much pullout resistance compared to conventional foundations. When applied to the anchors of floating type offshore wind turbines, particularly the Tension Leg Platform (TLP) type, the technology can reduce installation costs by approximately 20% and foundation work costs by approximately 30%.

These innovations in foundation technology complement the wind turbine wall by addressing different aspects of offshore wind development challenges. While the turbine wall focuses on maximizing energy generation efficiency, technologies like Skirt Suction address installation and maintenance challenges that have historically made offshore wind prohibitively expensive in many locations.

The broader context of offshore wind technology development includes various floating platform designs including semisubmersible, spar, and Tension Leg Platform types. Each design offers different advantages for specific ocean conditions and depths, with Japan’s unique geography and seismic activity requiring tailored solutions.

Broader Japanese Innovations in Renewable Energy

Japan’s focus on wind turbine wall technology represents just one aspect of the country’s broader push for renewable energy innovation. Japanese engineers have also been developing revolutionary solar technologies that challenge conventional approaches to renewable energy generation.

Kyosemi Corporation has developed Sphelar, a family of tiny spherical solar cells designed to collect light from multiple directions. These cells, typically one to two millimeters in diameter, are wired together to form modules. Their spherical shape allows them to capture light from various angles throughout the day, overcoming the limitations of flat panels that are only efficient when directly facing the sun.

The development of these spherical cells began with engineer Shuji Nakata’s observation that sunlight rarely travels in a straight line. This led to the innovative use of microgravity conditions at the Japan Microgravity Center (JAMIC) to form near-perfectly round silicon beads. The technology opens up possibilities for embedding solar power into transparent materials and curved surfaces, making it ideal for applications in dense urban settings.

Other Japanese innovations include rock thermal storage technology led by Toshiba Energy Systems along with Chubu Electric Power Company. This system uses rocks to efficiently absorb and release heat, storing thermal energy that can later be used to generate electricity by heating water and driving a turbine. Rock thermal storage offers advantages including the absence of rare metals like cobalt and nickel that are essential for battery storage, along with a long lifespan and minimal site constraints.

Japan is also focusing on scaling up domestically produced renewable energy sources, including next-generation solar cells that can be installed on building roofs and walls. The country holds a strategic advantage in perovskite solar cell production, as it produces 30% of the world’s iodine, a key material for these cells. The government has allocated JPY 64.8 billion to the Next Generation Solar Cell Development Project to bring these advanced cells into widespread use by 2030.

Supply Chain and Infrastructure Considerations

Despite technological innovations, Japan’s offshore wind sector faces significant supply chain challenges that threaten to undermine progress. The construction of wind turbines requires a range of materials including steel, fibreglass and rare earth elements, all of which face market complexities and geopolitical considerations.

Steel serves as the backbone of wind development, constituting up to 90% of a turbine’s mass. The global steel supply chain has experienced extreme volatility, exacerbated by geopolitical developments and trade tensions. China dominates global steel production and wind power manufacturing, undercutting global competition with cheap and heavily subsidised exports.

Markus Zeitzen, wind energy service provider Det Norske Veritas (DNV) ESG senior business development manager, emphasized the need for supply chain diversification when he said:

Selecting two or three suppliers from different areas can give you resilience in your supply chain through competition.

Rare earth elements present another challenge. Out of the 17 classified REEs, four are primarily used in wind turbines: neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium. These are essential for producing permanent magnets that generate electricity and maintain turbine integrity. China controls 60% of global REE mined production and roughly 90% of global processing output, creating significant supply chain vulnerabilities.

In December 2023, China initiated an export ban on separation and extraction technologies for manufacturing permanent magnets, which has escalated to export controls on seven REEs. This development has prompted global shifts toward proactive supply chain risk management, with the EU investing in innovations to secure critical raw materials.

These supply chain challenges have real-world impacts on project viability. In December 2024, wind developer Ørsted cited supply chain bottlenecks as a key reason for opting out of Denmark’s offshore wind farm tender, which received no bids overall. Similarly, in February, Mitsubishi paused its plans for offshore wind projects in Japan, pointing to supply chain issues.

International Perspectives and Investment Strategies

While Japan faces challenges in domestic offshore wind deployment, Japanese companies are increasingly investing in international renewable energy projects to gain expertise and secure positions in growing markets. Japanese investors are turning to Europe and Norway in particular for strategic growth in energy and sustainability sectors.

Nick Wall, Tokyo-based partner at A&O Shearman, explained this trend when he said:

Norway offers Japanese investors the stability they’re looking for—strong property rights, a transparent legal system, and access to the EU single market through the EEA. As geopolitical and regulatory uncertainty grows in markets like the US and parts of Asia, we’re seeing Japanese investors increasingly diversify into stable European jurisdictions like Norway to mitigate legal and operational risks.

Japanese investments in Norway have been active in the oil & gas and utility sectors, which accounted for eight out of 23 total deals between 2020 and 2025. Japanese exploration and production companies see strong growth potential in offshore wind power, particularly floating, power-from-shore solutions, and carbon capture and storage (CCS) in Europe.

INPEX Corp, Japan’s largest oil and gas exploration and production company, positions Europe as a core business area and is pursuing development opportunities there. A spokesperson for INPEX noted the company’s participation in the Hywind Tampen project, one of the world’s largest floating offshore wind farms (88MW) that supplies electricity to oil and gas facilities. This project reduces CO2 emissions by about 200,000 tons per year.

This international investment strategy allows Japanese companies to gain experience with established offshore wind technologies while continuing to develop domestic innovations like the wind turbine wall. The knowledge gained from these international investments can inform future domestic deployments as Japan works to address regulatory and infrastructure challenges.

The Japanese government has also emphasized cooperation with local communities through initiatives by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). These efforts integrate renewable energy sources with specific industries, linking forestry with biomass energy, fisheries with offshore wind power, livestock farming with biogas, and agriculture with solar power. These tailored approaches aim to minimize environmental impact, return energy benefits to local communities, and prevent challenges associated with external developers with no ties to the area.

The Path Forward for Japan’s Renewable Energy Leadership

Japan’s wind turbine wall technology represents more than just an incremental improvement in wind energy—it symbolizes the country’s determination to overcome energy security challenges through innovation. However, technological breakthroughs alone cannot ensure success in the renewable energy transition.

Masataka Nakagawa, OWC’s Japan Country Manager, emphasized the comprehensive nature of the changes needed when he said:

To enable stable and scalable deployment, Japan needs to address three critical areas: auction framework, offtake mechanisms, and other market bottlenecks.

The window of opportunity for Japan to establish itself as a leader in offshore wind technology is narrowing. Other markets in Asia are rapidly building clean energy infrastructure, and international investors are mobile, directing capital to markets with clear, stable frameworks. Supply chain partners need demand visibility to justify investments in local manufacturing.

For a nation that pioneered hybrid cars and led in solar deployment before feed-in tariffs lapsed, failing to capitalize on its offshore wind potential would represent more than an industrial missed opportunity. It would be a strategic failure at precisely the moment when energy security, economic competitiveness, and climate leadership demand bold action.

The wind turbine wall technology developed by Kyushu University offers Japan a potential path to leapfrog competitors and establish technological leadership in offshore wind. Combined with complementary innovations like Skirt Suction foundations and spherical solar cells, Japan has demonstrated remarkable capability for renewable energy innovation.

Whether these technological breakthroughs can translate into commercial success depends on Japan’s ability to address the structural challenges in its offshore wind sector. The GWEC white paper has presented clear recommendations for reform, and government agencies have expressed strong interest. The question remains whether Japan will act decisively enough, quickly enough, to create the conditions necessary for these innovations to flourish.

As the world races toward decarbonization, offshore wind power alone could theoretically meet the entire electricity needs of Europe, the U.S., and Japan many times over, according to the International Energy Agency. Japan’s wind turbine wall could play a crucial role in unlocking this potential, offering a way to dramatically increase energy generation while addressing land and resource constraints.

Key Points

- Kyushu University has developed an innovative wind turbine wall technology with potential to triple power output compared to conventional offshore wind turbines.

- Japan faces urgent energy challenges with self-sufficiency at just 15.2% and fossil fuels comprising 72.8% of its energy mix.

- The wind turbine wall builds upon floating wind technology that can access deeper waters with stronger, more consistent winds.

- Japan’s offshore wind sector faces significant hurdles including auction framework issues, revenue uncertainty, and supply chain challenges.

- Complementary Japanese innovations include Skirt Suction foundations, spherical solar cells, and rock thermal storage technology.

- Japanese companies are investing in international offshore wind projects, particularly in Europe and Norway, to gain expertise.

- Japan aims to increase renewable energy share from 20% to 36-38% by 2030, with offshore wind playing a crucial role.

- The government has secured offshore areas for demonstration tests and invested JPY 123.5 billion through the Green Innovation Fund.

- Global floating wind capacity reached 245 MW as of October 2024 with a future pipeline of 266 GW worldwide.

- Japan’s energy strategy emphasizes community cooperation and industry-specific renewable integration approaches.