A Tale of Two Demographic Futures

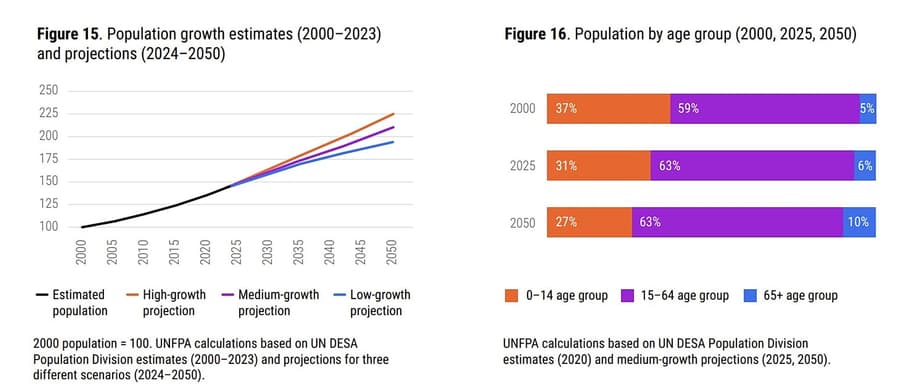

Central Asia is entering a decisive demographic phase characterized by rapid population growth and a sharply expanding workforce, while Europe faces aging societies and labor shortages. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Central Asia’s population is projected to exceed 114 million by 2050, marking a significant divergence from trends in Europe and East Asia where declining birth rates and aging populations have become dominant concerns. For families across Central Asia, these demographic trends represent daily realities shaped by cultural traditions, economic conditions, and personal choices that differ markedly from those influencing European households.

The contrast extends beyond mere population numbers to fundamental differences in age structure, economic potential, and social dynamics. While European nations grapple with shrinking workforces and increasing dependency ratios, Central Asian countries are experiencing what demographers describe as a rare demographic window—a temporary period when a large youth population creates opportunities for accelerated economic growth, provided the right investments are made in education, healthcare, and job creation. This divergence presents both challenges and opportunities for policymakers across the Eurasian continent, with implications extending far beyond national borders.

Understanding the Demographic Window

Central Asia is experiencing a demographic phenomenon that economists and development experts closely watch. According to the UNFPA report, the population of working-age adults aged 15-64 across the region is projected to increase from approximately 50 million today to approximately 71 million by 2050. This expansion represents more than 20 million additional women and men entering the labor market over the next quarter-century, creating a significant potential for economic growth and innovation if properly harnessed.

Nearly one-third of Central Asia’s population is under the age of 15, meaning education systems, labor markets, and social institutions will face sustained pressure in the coming decades. Nigina Abbaszade, UNFPA representative in Uzbekistan, emphasized that this demographic momentum creates a limited but critical opportunity for the region.

“Whether this growth translates into economic and social gains depends on how well countries prepare now,” Abbaszade said. “Investment in education, healthcare, and decent employment, particularly for women and young people, is essential to ensure that the growing population contributes productively to society.”

Expanding women’s access to education and work plays a key role in shaping long-term demographic and economic outcomes, according to Abbaszade. The demographic dividend—the economic growth potential that can result from shifts in a population’s age structure—is not automatic. It requires deliberate policy choices and significant investment in human capital. Without these investments, countries risk facing unemployment, reliance on migration, environmental strain, and social fragmentation.

Uzbekistan at the Heart of the Boom

Uzbekistan stands as the most populous country in Central Asia, exemplifying the region’s demographic trajectory. With 37.4 million people in 2024, it accounts for nearly half of the region’s population. By 2050, that figure is projected to reach 52 million, representing substantial growth that will shape the country’s economic and social landscape for decades to come. The country’s demographic growth is reflected in daily statistics, with 1,815 children born in Uzbekistan in the first 24 hours of 2026 alone, including 894 girls and 921 boys. The highest number of births was recorded in the Surkhandarya region, with 243 newborns.

A defining feature of Uzbekistan’s demographic profile is its youthfulness. Around 60% of the population is under 30, creating strong momentum for economic growth, innovation, and labor market expansion. The country’s population is growing at around 2% per year, nearly twice the global average. According to Uzbekistan’s National Statistics Committee, the population increases by roughly 740,000 people annually, with the highest birth rates recorded in the Surkhandarya region in southern Uzbekistan. This growth underscores the importance of sustained investment in education, skills development, and job creation, as the number of working-age citizens increases by approximately 350,000 each year.

Kazakhstan’s Demographic Transition

Kazakhstan presents a different demographic picture within Central Asia, offering a glimpse into the region’s future as it progresses through demographic transition. With a population of 20.3 million in 2025, it has increased by 23% since 1992 and is projected to reach approximately 26 million by 2050. A significant portion of Kazakhstan’s population remains young, with around 29-30% aged 0-14, indicating a strong presence of children and adolescents in the age structure. This proportion helps sustain demographic momentum even as the country gradually moves through a demographic transition.

While fertility remains relatively high at around three children per woman, Kazakhstan is entering a more advanced stage of demographic transition compared to its Central Asian neighbors. By 2050, the share of people aged 65 and older is expected to nearly double: from 8% to almost 15%. Population trends vary across Kazakhstan, with growth concentrated in the south and west, whereas northern regions experience population decline and slower economic activity. These regional variations highlight the complex nature of demographic change within countries, requiring nuanced policy approaches that address local conditions and needs.

The Human Stories Behind the Numbers

Behind the regional data are families making deeply personal decisions about family size and structure. For Sayyora Mamaraimova, a 59-year-old homemaker from Uzbekistan, growing up in a large family shaped her desire to have children of her own.

“In our family there were eight of us. We always supported each other,” Mamaraimova said. “That’s why I wanted my children to have siblings, so they would never feel alone.”

Mamaraimova had five daughters while carefully considering health and financial limits.

“No matter how many children you have, you still have to think about education, food, and the future,” she added.

Feruza Saidhadjaeva, also from Uzbekistan, combined motherhood with a long professional career. She worked continuously while raising four children and believes planning and women’s independence are essential.

“Financial responsibility matters. I never wanted to depend on anyone,” Saidhadjaeva said. “Large families have many positives, but they require discipline, planning, and equal responsibility.”

In Kazakhstan, Azhara Kabitova, a mother of six including twins and triplets, describes how family size is shaped by both cultural values and everyday realities.

“Culturally, having many children is encouraged,” Kabitova said. “But families still have to think carefully about finances and long-term planning.”

These personal narratives reveal that while cultural norms influence family size decisions, economic realities and personal aspirations play equally important roles.

Europe’s Demographic Challenge

Central Asia’s demographic trajectory contrasts starkly with trends in Europe. Eurostat data indicate that the EU’s total fertility rate is approximately 1.38 births per woman, well below the replacement level of 2.1, while life expectancy continues to rise. Together, these trends are reshaping labor markets, welfare systems, and social policies across the continent. The implications are profound: without significant immigration or policy changes, many European countries face shrinking workforces and increasing dependency ratios that threaten economic sustainability and social security systems.

For families living in Europe, the contrast with Central Asia is striking. Ilkhom Khalimzoda, an Uzbek citizen who lives in Finland, said Europe’s individualized lifestyle makes large families more difficult.

“Every child requires more time, energy, and money, and parents do almost everything themselves,” Khalimzoda explained. “There is no extended family support like in Uzbekistan.”

Jonas Astrup, a Danish father of three, notes that in northern Europe one or two children is the norm, while larger families are often viewed as an exception. In Europe, women’s fertility decisions are more closely tied to career planning, housing costs, and work–life balance. In Central Asia, family size remains more strongly influenced by cultural norms and intergenerational support, although this is gradually changing as economic conditions evolve.

Economic Implications and Policy Responses

The demographic divergence between Central Asia and Europe has significant economic implications that policymakers must address. According to the World Bank’s Europe and Central Asia Economic Update, growth in the developing economies of Europe and Central Asia is expected to slow from 3.7% in 2024 to 2.4% in 2025, driven primarily by a weaker pace of expansion in the Russian Federation. The region is also facing a serious jobs challenge, where most of the jobs created over the last 15 years have been in relatively low-skilled roles with limited earning potential.

Investing in infrastructure, improving the business environment, and mobilizing private capital will be critical to jumpstarting productivity, creating jobs, and building a more resilient labor market given the region’s shifting demographics. The report emphasizes that demographic headwinds—including aging and lower fertility rates—and slowing productivity growth threaten the resilience of the region’s labor market, compounding the jobs challenge. Changing this will require bold reforms, specifically ramping up investment in infrastructure, improving the business environment, and mobilizing private capital.

The region’s heterogeneity implies that countries cannot follow a single approach to tackling the jobs challenge. For instance, compared to the rest of the region, the demographic pressures are different in Central Asia and Türkiye, where increasing the number of jobs employing the growing young population is an urgent priority. In the Western Balkans or Central Europe, in a context of a shrinking workforce, it will be crucial to upgrade jobs in terms of quality and productivity. Success will depend on country ownership, tailored approaches, and leveraging assets such as human talent and natural resources.

Environmental and Infrastructure Pressures

By mid-century, Central Asia’s growing population will place increasing pressure on water resources, land, and urban infrastructure, particularly in vulnerable areas such as the Aral Sea region and the Fergana Valley. These environmental challenges intersect with demographic trends in complex ways. Research published in Nature indicates that urban areas worldwide are facing increasing environmental pressures from air pollution and carbon emissions, with rapidly growing regions experiencing overall increases in pollutants despite efforts to improve air quality in high-income countries.

Without sufficient job creation, education, and social protection, the risks include unemployment, reliance on migration, environmental strain, and social fragmentation. The challenge is particularly acute given the region’s vulnerability to climate change, with projections suggesting increased exposure to extreme weather events that could disproportionately affect vulnerable populations. Central Asian governments will need to balance economic development with environmental sustainability, investing in climate-resilient infrastructure and sustainable urban planning to accommodate population growth without exacerbating environmental degradation.

What the Future Holds

Looking ahead, demographic projections suggest that the contrast between Central Asia and Europe will likely intensify in the coming decades. According to a major study published in The Lancet, the global population is projected to peak in 2064 at 9.73 billion people before declining to 8.79 billion by 2100. This global trend masks significant regional variations, with Central Asia experiencing continued growth while much of Europe faces population decline. The study notes that continued trends in female educational attainment and access to contraception will hasten declines in fertility and slow population growth, creating different challenges across regions.

UNICEF’s projections for children in 2050 highlight that Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia will have the largest child populations, while Europe and Central Asia will see aging populations with decreasing shares of children. These demographic shifts create challenges, with some countries under pressure to expand services for large child populations, while others balance the needs of a growing elderly population. The report underscores that the decisions world leaders make today—or fail to make—will define the world children will inherit in 2050 and beyond.

For Central Asia, the coming decades represent a critical period. With sustained investment in human capital and labor markets, the region may be better positioned to integrate its growing youth population at a time when many European countries are facing labor shortages. This could create new opportunities for regional cooperation and economic partnership, potentially reshaping the relationship between Central Asia and Europe in ways that benefit both regions. However, realizing this potential will require foresight, strategic investment, and policy choices that prioritize the well-being and future opportunities of all citizens.

Key Points

- Central Asia’s population is projected to exceed 114 million by 2050, with working-age adults growing from 50 million to 71 million

- Nearly one-third of Central Asia’s population is under 15, creating significant pressure on education and job markets

- Uzbekistan, the region’s most populous country with 37.4 million people, grows at 2% annually with 60% of its population under 30

- Kazakhstan shows a more advanced demographic transition, with the 65+ age group expected to nearly double to 15% by 2050

- Europe’s fertility rate of 1.38 births per woman remains well below the replacement level of 2.1

- World Bank projects economic growth in Europe and Central Asia slowing from 3.7% in 2024 to 2.4% in 2025

- Environmental pressures including water scarcity and urban infrastructure challenges will intensify with population growth

- Investment in education, healthcare, and decent employment is essential to convert demographic growth into economic gains