Why China pressed pause now

China has pressed pause on the Circular Electron Positron Collider, a 100 kilometer ring designed as a Higgs factory. The move follows the decision to leave the project out of the next national five year plan that runs 2026 to 2030. Officials and senior scientists describe a pause rather than a cancellation. Work on designs and research continues, but there is no construction timeline. The decision carries weight beyond China. It reshapes the contest to build the next flagship collider, and it gives Europe a chance to set the pace if the Future Circular Collider (FCC) is approved.

- Why China pressed pause now

- What the CEPC is and what it would do

- Costs, politics, and a tougher economy

- Where Europe and other players stand

- Design work did not stop

- Impact on scientists, suppliers, and students

- Power use and environmental scrutiny

- Smaller or distributed projects while the big ones wait

- What to Know

Rising costs and a tighter economy lie behind the pause. Prices for advanced materials and civil construction rose over the past decade. Local government debt limits reduce room for large upfront spending. National priorities have tilted toward faster payback in areas like semiconductors, satellites, and space. The case for mega science must now compete with industrial policy and near term technology goals. Those pressures are visible in Europe as well, where CERN’s Future Circular Collider still awaits political and financial commitments.

Particle physicists hoped CEPC would provide a decade of precise measurements of the Higgs boson, the quantum field that gives mass to elementary particles. A Higgs factory would measure Higgs couplings far more precisely than proton colliders can, test the electroweak sector with high accuracy, and set tight limits on new physics. The scientific case matured, the collaboration grew, and technology choices solidified. Yet in a budget constrained world even a strong case does not guarantee shovels in the ground.

What the CEPC is and what it would do

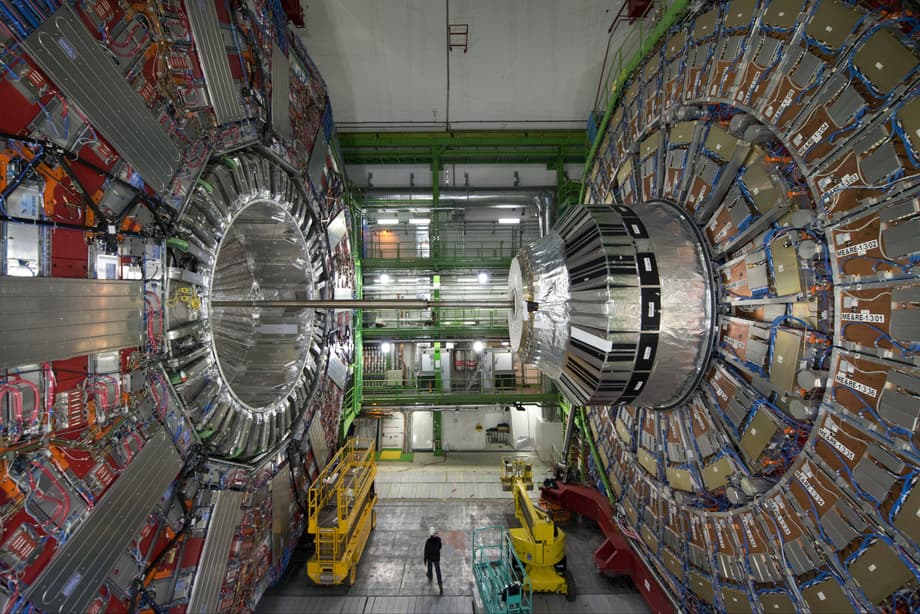

The CEPC is a circular collider that brings electrons and positrons into head on collision at energies tuned to produce large numbers of Higgs bosons. Compared with proton machines like the Large Hadron Collider, an electron positron machine delivers much cleaner events. When protons collide they break apart into showers of quarks and gluons, which makes precision measurements hard. Electrons and positrons are point like, so their collisions are simpler to interpret. A Higgs factory can scan several energy settings, generate millions of Higgs events, and measure key properties with percent level or sub percent accuracy.

The layout foresees a tunnel of roughly 100 kilometers with two interaction points, injector accelerators, cryogenics, and a new generation of detectors. The plan includes a long Higgs run near 240 GeV, then dedicated periods at the Z boson peak and the WW threshold to map the electroweak interaction with unprecedented statistics. The same tunnel could host a later proton collider, often called Super Proton Proton Collider, that would push discovery reach far beyond the Large Hadron Collider. That two stage roadmap is similar to the concept in Europe for FCC.

Technical work reached key milestones. A conceptual design report appeared in 2018. The accelerator technical design report followed in 2023. In 2025 the study group released a reference detector report that proposes an electromagnetic calorimeter made of orthogonal crystal bars, a hadronic calorimeter built on high granularity scintillating glass, and a new tracking system based on low gain avalanche diode sensors that combine about 10 micrometer spatial precision with about 50 picosecond timing. A readout chip in 55 nanometer technology aims to cut power needs by roughly two thirds while improving resolution and integration.

Costs, politics, and a tougher economy

A project of this scale needs steady funding for more than a decade. Early cost estimates for CEPC spread widely, from about 5 billion dollars to figures near 10 billion dollars once civil works, power systems, and detectors are included. Inflation in construction materials, higher borrowing costs, and global supply chain friction all pushed projections upward. At the same time, national and provincial leaders in China are steering money into strategic industries. The combination made it harder to lock in a firm schedule and a multi year budget line for CEPC.

Chinese science planners did not include CEPC in the 2026 to 2030 plan. Project leaders say they will keep the collaboration active and resubmit in 2030. They also state that if Europe gives a green light to the Future Circular Collider before then, China would consider joining FCC rather than running two parallel programs. That approach mirrors the global nature of high energy physics. Big accelerators need international partners, and the decision to host one collider often leads others to contribute rather than duplicate.

Where Europe and other players stand

Europe is weighing its own path. CERN’s proposed Future Circular Collider has a first stage that, like CEPC, would be a circular electron positron machine focused on Higgs and electroweak studies. Later stages could upgrade to a proton machine in the same tunnel. The circumference is similar to CEPC, although FCC plans and costs differ. A recent estimate for FCC runs into tens of billions of dollars. Member states are testing public support, environmental feasibility, and long term energy supply. The European Strategy for Particle Physics process is expected to frame recommendations mid decade, with a decision on FCC closer to 2028.

Other proposals remain on the board. Japan studied the International Linear Collider but has not moved to construction. The United States community endorsed a strong program of research and development on a muon collider, while also supporting participation in a Higgs factory if one is built abroad. That makes the next few years decisive. If Europe commits to FCC, it will likely draw partners from Asia and North America. If Europe also hesitates, the field may continue with smaller projects until economic and political conditions stabilize.

Design work did not stop

CEPC scientists stress that the pause does not mean the end of progress. The design reports give a mature blueprint. R and D on key technologies is active, from high yield scintillating glass to large area silicon sensors and power efficient readout chips. An international review panel examined the detector concept through several cycles and concluded that the design is coherent and reaches the needed physics performance. The next steps focus on integrated prototypes, system tests, and engineering design so that a restart can move quickly if funding arrives.

That work spills over into other fields. Advances in fast timing sensors can feed medical imaging. New cryogenic, vacuum, and power systems can help energy and aerospace industries. Big detector software improves data science. This spillover is part of the case advocates make when budgets tighten. National leaders often ask for practical benefits. The story of particle physics includes many: the web at CERN, hadron therapy for cancer, superconducting wire, and advances in magnet technology. A Higgs factory would likely add to that list.

Impact on scientists, suppliers, and students

A pause changes careers and supply chains. Young physicists look for projects that will deliver data during their early tenure years. Engineers in industry need predictable orders to invest in tooling for cryomodules, magnets, and detector components. Without a construction start, some will focus on nearer term programs. Reports from Chinese institutes already point to shifts into semiconductors, quantum testbeds, satellites, and other national priorities. That is a rational response. It also shows why observers track real world signals like contracts, land use permits, tunnel boring tenders, and long term hiring rather than press statements.

Power use and environmental scrutiny

Large colliders draw a lot of electricity. A Higgs factory would need hundreds of megawatts at peak. Power costs and carbon targets matter for host countries. CERN is studying ways to recover waste heat, integrate with district heating, and time power use to grid conditions. Similar efforts would be necessary in China. Environmental reviews also examine the geology along the tunnel, groundwater, and surface infrastructure. The technology community has learned lessons from earlier projects, with more attention on energy efficient RF systems and magnets.

Smaller or distributed projects while the big ones wait

The pause invites a debate about balance. Physicists can push forward with a mix of projects that each probe different pieces of the puzzle. Neutrino experiments map a sector the Standard Model leaves open. Cosmic surveys test gravity and dark energy on the largest scales. Tabletop experiments and quantum sensors search for ultralight dark matter and tiny symmetry violations. Particle physics, like space exploration, has always mixed flagships with a fleet of smaller missions. A healthy portfolio keeps talent engaged and maintains public support.

When the field is ready to break ground on the next collider, the choice will depend on which host can align science goals, funding, and public acceptance. The window is open for Europe to lead with FCC if it can clear technical, financial, and environmental questions. China can return with CEPC if conditions improve after 2030. Either path would deliver a Higgs factory, the tool that many theorists and experimentalists judge most urgent for precision tests. Until then, the community is working to keep the science case sharp and the technology ready.

What to Know

- China did not cancel CEPC, but it is paused after exclusion from the 2026 to 2030 five year plan.

- Design and research continue, with a plan to resubmit the proposal in 2030.

- Project leaders say China may join Europe’s FCC if that collider is approved first.

- CEPC reached major milestones, including accelerator and detector design reports and a positive international review of the detector concept.

- Cost pressure, local debt, and a pivot to tech with faster payback weighed on the decision to pause.

- Europe is evaluating FCC with a strategy process expected mid decade and a decision closer to 2028.

- The same 100 kilometer tunnel planned for CEPC could later host a high energy proton collider.

- Scientists see near term impacts on careers and suppliers, with some shifting to semiconductors, quantum testbeds, and satellites.

- Energy demand and environmental assessments are central to public acceptance for any next collider.

- While the next flagship waits, smaller projects in neutrinos, cosmology, and precision tabletop experiments will carry key parts of the field forward.