Japan’s Historic Romanization Reform: Why the Switch to Hepburn Matters

Japan is on the verge of a major language reform, set to update its official system for writing Japanese words in the Latin alphabet for the first time in seven decades. The Agency for Cultural Affairs has formally recommended that the government replace the long-standing Kunrei-shiki (Kunrei) romanization system with the more internationally recognized Hepburn system. This change, expected to be approved within the current fiscal year, will have wide-ranging effects on education, signage, and how Japan presents itself to the world.

- Japan’s Historic Romanization Reform: Why the Switch to Hepburn Matters

- What Is Romanization and Why Does It Matter?

- Why Is Japan Changing Its Romanization System Now?

- The History Behind Japan’s Romanization Systems

- How Will the New System Be Implemented?

- Why Has Kunrei Lasted So Long?

- Broader Implications: Education, Technology, and Global Communication

- Expert Perspectives and Public Reaction

- Looking Ahead: What’s Next for Japanese Romanization?

- In Summary

What Is Romanization and Why Does It Matter?

Romanization refers to the practice of writing Japanese words using the Latin alphabet, known in Japanese as rōmaji. While Japanese is traditionally written with a mix of kanji (Chinese characters) and kana (syllabic scripts), romanization is essential for contexts where non-Japanese speakers need to read or pronounce Japanese—such as on street signs, passports, textbooks, and digital devices.

Japan has used several romanization systems over the years, but the three main ones are:

- Hepburn: Developed by American missionary James Curtis Hepburn in the late 19th century, this system is designed to match English phonology, making it intuitive for English speakers.

- Kunrei-shiki: Codified by the Japanese government in 1954, this system is more systematic and closely follows the Japanese syllabary, but is less intuitive for foreigners.

- Nihon-shiki: An even stricter system based on the kana, used mainly by linguists and some religious groups.

For decades, Japan’s official documents and school curricula have used Kunrei-shiki, but in practice, Hepburn has dominated in public life, especially in signage and international contexts.

Why Is Japan Changing Its Romanization System Now?

The move to adopt Hepburn romanization comes after years of confusion and inconsistency caused by the coexistence of multiple systems. While the Kunrei system was the official standard, most Japanese people and foreigners alike have become accustomed to Hepburn spellings. For example, under Kunrei, the Tokyo district of Shibuya would be written as “Sibuya,” and the central prefecture of Aichi as “Aiti.” These spellings often confuse non-Japanese speakers, as they do not reflect actual pronunciation.

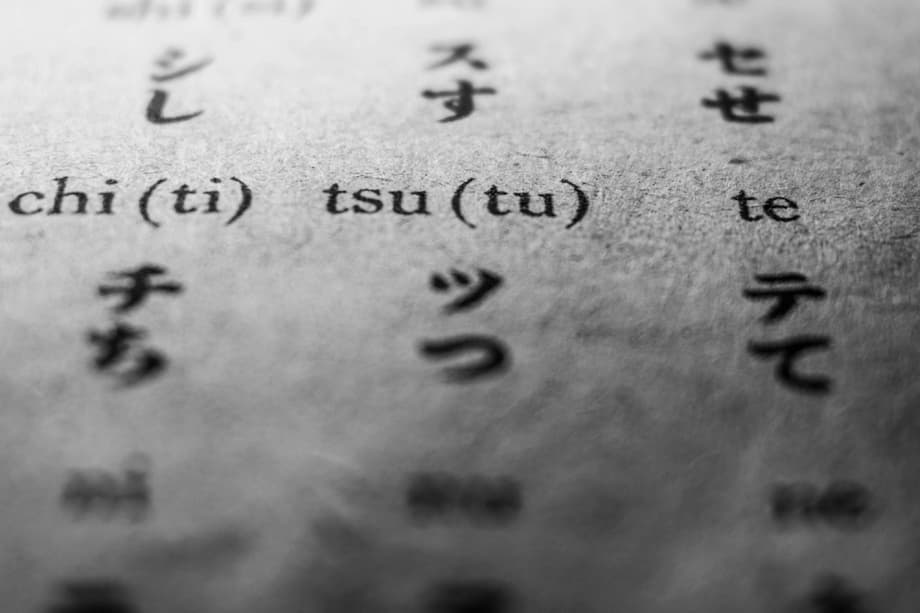

As SoraNews24 explains, the Kunrei system’s logic is based on the structure of the Japanese syllabary, grouping syllables by consonant-vowel lines. However, this leads to unintuitive spellings for those unfamiliar with Japanese phonetics. For instance, the syllable “shi” is rendered as “si,” and “chi” as “ti.” The Hepburn system, by contrast, spells these as “shi” and “chi,” closely matching how they sound to English speakers.

According to Kyodo News, the gap between official rules and common usage has led to confusion in everything from school textbooks to passport processing. The Agency for Cultural Affairs began reviewing the rules in 2022, and a subcommittee of the Council for Cultural Affairs has now recommended the switch to Hepburn to improve communication and reduce misunderstandings.

Examples of the Change

Here are some common words and place names, showing how they differ between the two systems:

- Shibuya (Hepburn) vs. Sibuya (Kunrei)

- Aichi (Hepburn) vs. Aiti (Kunrei)

- Fukushima (Hepburn) vs. Hukusima (Kunrei)

- Sushi (Hepburn) vs. Susi (Kunrei)

These differences, though subtle, can make a significant impact on how Japanese words are perceived and pronounced by non-native speakers.

The History Behind Japan’s Romanization Systems

The use of the Latin alphabet to write Japanese dates back to the 16th century, when Portuguese missionaries developed the first system to help spread Christianity. Over time, several systems emerged, but the most influential was the Hepburn system, introduced in the late 1800s by James Curtis Hepburn, who compiled a Japanese-English dictionary for Westerners.

During the early 20th century, some Japanese scholars even advocated for replacing the entire Japanese writing system with romanization, but this movement never gained widespread support. In 1937, the Japanese government established Kunrei-shiki as the standard, and this was reaffirmed in 1954 by a Cabinet notification. The Kunrei system was seen as more logical and systematic, aligning closely with the kana syllabary and Japanese grammar.

However, as Japan opened up to the world and English became the global lingua franca, the Hepburn system’s intuitive approach to pronunciation made it the preferred choice for foreigners and in international contexts. Today, Hepburn is used on road signs, in passports, and in most English-language materials, while Kunrei remains largely confined to school textbooks and some official documents.

How Will the New System Be Implemented?

The Agency for Cultural Affairs’ recommendation is expected to be approved by the education minister, after which the Hepburn system will gradually replace Kunrei in educational materials and official documents. The transition will not be immediate; instead, it will be phased in over several years to allow schools, publishers, and government agencies to adapt.

According to Asahi Shimbun, the new guidelines will standardize the use of Hepburn spellings for syllables like “shi,” “chi,” “tsu,” and “fu.” Double consonants will be written by repeating the consonant (e.g., “teppan” for てっぱん), and long vowels can be indicated with either a macron (e.g., “kāsan” for かあさん) or doubled letters (“kaasan”). The guidelines also allow for flexibility in personal and organizational names, letting individuals and entities choose their preferred spelling.

The council’s proposal also acknowledges practical challenges, such as the difficulty of typing macrons on electronic devices. Therefore, it allows for alternative spellings without diacritics (e.g., “judo” instead of “jūdō”) or with an added “h” (e.g., “Ohtani” for the baseball star Shohei Ohtani).

Public Consultation and Response

The Agency for Cultural Affairs has opened a public comment period, inviting feedback from citizens and stakeholders. Officials have emphasized that the new system is not intended to invalidate other popular methods, but to provide a clear and consistent standard for official and educational use.

Why Has Kunrei Lasted So Long?

Despite its lack of popularity outside Japan, Kunrei-shiki has endured for decades due to its systematic approach and its alignment with Japanese grammar and phonetics. As Japan Times notes, Kunrei is more faithful to the inner logic of Japanese, including etymology and word formation. However, this very logic makes it less accessible to non-Japanese speakers, who often struggle to pronounce words spelled according to Kunrei rules.

For example, the Kunrei spelling “susi” does not convey the correct pronunciation to someone unfamiliar with Japanese, whereas “sushi” (Hepburn) does. The same applies to “ti” (Kunrei) versus “chi” (Hepburn), and “hu” (Kunrei) versus “fu” (Hepburn).

In practice, most Japanese people use Hepburn spellings in daily life, especially when interacting with foreigners or using English-language materials. The persistence of Kunrei in schools and official documents has created a disconnect between what is taught and what is actually used, prompting calls for reform.

Broader Implications: Education, Technology, and Global Communication

The switch to Hepburn romanization is more than a technical adjustment—it reflects Japan’s ongoing efforts to modernize and internationalize its society. By aligning official standards with common practice, the reform aims to:

- Improve English education: Teachers will be able to focus on a system that matches what students encounter in real life, reducing confusion and making it easier to learn correct pronunciation.

- Simplify signage and documentation: Consistent romanization will make it easier for foreigners to navigate Japan, whether they are tourists, business travelers, or residents.

- Enhance digital communication: As more Japanese is written and read on computers and smartphones, a standardized, intuitive romanization system will streamline input methods and reduce errors.

- Support international branding: Japanese companies, organizations, and individuals will benefit from having their names and products spelled in a way that is easily understood and pronounced by a global audience.

As Language Log points out, the rise of digital technology has increased the use of romanization in Japan, especially for computer input and international communication. The new guidelines are designed to accommodate these trends, allowing for flexibility in how long vowels and certain consonants are represented.

Expert Perspectives and Public Reaction

Linguists and educators have generally welcomed the proposed reform. Many see it as a long-overdue step toward clarity and consistency. As one language expert told Japan Times:

“The agency can only be congratulated for its bold proposal. The differences between the two systems concern only a handful of syllables, and yet they are the source of much confusion.”

However, some traditionalists argue that Kunrei-shiki’s systematic approach has educational value, especially for understanding the structure of the Japanese language. The Agency for Cultural Affairs has sought to address these concerns by allowing flexibility in personal and organizational names, and by not requiring immediate changes to existing materials.

Public response has been largely positive, with many Japanese people expressing relief that the official standard will finally match what they see on signs, in passports, and in international media. The move is also seen as a practical step to make Japan more accessible to visitors and to support the country’s global engagement.

Looking Ahead: What’s Next for Japanese Romanization?

The adoption of Hepburn romanization marks a significant milestone in Japan’s linguistic history. While the transition will take time, the benefits of a unified, intuitive system are clear. As Japan continues to play a leading role on the world stage, clear and consistent communication will be more important than ever.

For now, the government is focused on finalizing the new guidelines, gathering public input, and preparing for a gradual rollout in schools and official documents. The reform is a testament to Japan’s willingness to adapt and modernize, while respecting its linguistic heritage.

In Summary

- Japan is set to replace the Kunrei-shiki romanization system with the more widely used Hepburn system for writing Japanese in the Latin alphabet.

- The change aims to reduce confusion, improve communication, and align official standards with common practice in signage, passports, and education.

- The Hepburn system is more intuitive for non-Japanese speakers, reflecting actual pronunciation more closely than Kunrei-shiki.

- The reform will be phased in gradually, with flexibility for personal and organizational names.

- Linguists, educators, and the public have largely welcomed the move as a practical step toward clarity and internationalization.