A Heavy Stone and a Heavy History

A massive 9.5-tonne stone monument has become the focal point of a renewed diplomatic and cultural campaign between China and Japan. The Tang Honglu Well Stele, a relic carved over 1,300 years ago, currently sits within the grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Researchers and activists argue that it belongs in China, from where it was removed more than a century ago. On Friday, Shanghai University’s Research Centre for Chinese Relics Overseas joined forces with Japanese cultural groups to issue a joint declaration. They urged Tokyo to “correct historical errors” and return the stone monument to its place of origin.

The call coincides with the release of a new book titled Compendium of Archival Documents on the Tang Honglu Well Stele. This publication aims to provide the historical evidence necessary to prove the artifact’s origins and the circumstances of its removal. According to Chinese state news agency Xinhua, the joint declaration represents a significant step in Beijing’s ongoing national campaign to reclaim cultural heritage lost during periods of conflict.

This effort is not merely about moving a heavy rock. It is about national identity, historical memory, and the complex relationship between two powerful Asian nations. The stele is physically imposing, standing nearly 1.8 meters tall and 3 meters wide. However, its historical weight far exceeds its physical mass, representing a tangible link to a golden era of Chinese civilization and its historical reach in northeastern territories.

“Returning looted Chinese artifacts should have been resolved in the last century. It keeps getting delayed. As Japanese citizens, we believe it’s our responsibility to urge the government to act – we cannot pass this burden on to the next generation.”

The above statement comes from Keiichiro Ichinose, a Japanese lawyer and founder of a civic organization dedicated to the return of cultural relics. His involvement highlights that the demand for restitution is not coming solely from the Chinese government, but also from civil society within Japan.

A Relic from the Golden Age

To understand the importance of the Tang Honglu Well Stele, one must look back to the Tang Dynasty, which lasted from 618 to 907 AD. Historians regard this era as a peak of Chinese culture and power, influencing art, literature, and politics across Asia. The stele was erected in 714 AD, during this flourishing period.

The monument is not just a decorative piece. It bears inscriptions that serve as critical historical records. Researchers identify these carvings as evidence of China’s early sovereignty over its northeastern territories. Specifically, the text documents interactions between the Tang court and the Bohai Kingdom. It mentions a Tang emissary named Cui Xin, who traveled to the region around Lushun, known historically as Bohai.

Wang Renfu, a Chinese historian who has spent two decades studying the stele, explains its significance. He notes that the artifact proves Cui Xin went to the region to establish China’s sovereignty over the people there. The inscription includes 29 Chinese characters detailing instructions for digging two wells. This seemingly mundane administrative task was recorded in stone to formalize the presence and authority of the Tang government in the area.

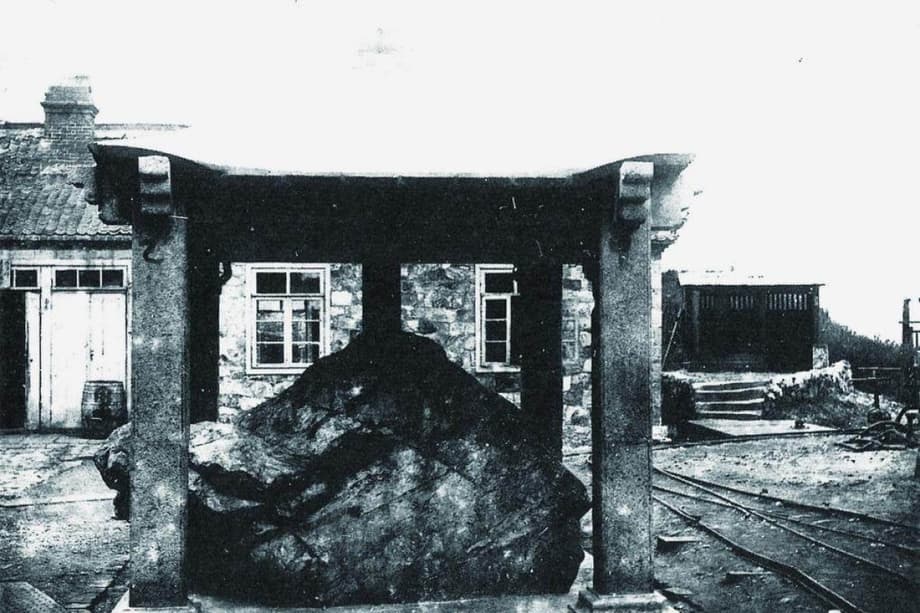

The stele remained in the Liaodong peninsula, the southern extension of today’s Liaoning province, for over a millennium. It stood as a silent witness to the rise and fall of dynasties, surviving through the Ming and Qing eras. The visible break marks on the pavilion’s pillars and the layered inscriptions from different dynasties tell a story of longevity and endurance until its removal in the early 20th century.

From Liaoning to Tokyo

The journey of the stele from its resting place in Liaoning to the Imperial Palace in Tokyo is a story of war and conquest. The removal occurred sometime between 1906 and 1908, a period of intense military conflict in Northeast Asia. This era followed the Russo-Japanese War, where Japan secured a decisive victory over Russia.

Historical documents suggest that the Japanese military viewed the stele as a symbol of their triumph. It was transported from Lushun, then known as Port Arthur, to Tokyo as a “war trophy.” This act was facilitated by Japanese wartime regulations established in 1894. These rules effectively sanctioned the “collecting” of treasures from occupied territories, turning cultural heritage into spoils of war.

Records from the Meiji era explicitly list the Stele Pavilion as a “war trophy” delivered to the Japanese Imperial Palace. The process involved significant logistical effort to move the 9.5-tonne stone. It was formally received by the palace on April 30, 1908, according to records later uncovered by researchers. Since that day, the artifact has remained hidden from the public eye, accessible only to the emperor and members of the imperial household.

Chinese scholar Qiao Dexiu first exposed the incident in 1911, shortly after the removal took place. However, his warnings did not lead to the artifact’s return. For over 120 years, the stele has remained in Japan, making it the largest and heaviest looted Chinese cultural relic in the possession of the Japanese Imperial Palace. The recent joint declaration seeks to finally reverse this historical wrong by presenting irrefutable proof of its illegal seizure.

Hidden in the Imperial Gardens

Today, the Tang Honglu Well Stele resides in the Fukiage Garden of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. It is housed within a protective pavilion that was also transported from the original site in China. Unlike many artifacts seized during war, which often end up in museums, this stele is kept as “national property” and is completely inaccessible to the general public.

Photographs released by the Imperial Palace to a Japanese peace group several years ago offer a rare glimpse of the artifact. The images show a massive stone set within the palace gardens, sheltered by the historic structure. The fact that it is hidden away has added to the frustration of those seeking its return. They argue that cultural treasures should be shared with the world, not locked away as private trophies of a bygone imperial era.

The location of the stele in the Imperial Palace adds a layer of complexity to any diplomatic negotiations. The Imperial Household Agency, which manages the palace grounds and the emperor’s affairs, oversees the site. Negotiations with this body are notoriously difficult. Activists attempted to negotiate through a supportive Japanese lawmaker, but talks stalled when that politician lost their seat.

This seclusion contrasts sharply with how other nations handle disputed artifacts. Many institutions around the world are engaging in open dialogues about repatriation, placing items in limbo or returning them proactively. In Japan, however, the stele remains out of sight and, until recently, largely out of the public consciousness regarding its origins.

Japanese Activists Take a Stand

While the Chinese government has long sought the return of lost artifacts, a significant force in this specific campaign comes from within Japan. The Chinese Cultural Relics Return Movement Promotion Association, founded in 2021, has been tirelessly working to raise awareness about the issue. They argue that returning these artifacts is a necessary step for Japan to fully reckon with its imperialist and colonial past.

Keiichiro Ichinose, the group’s founder, is no stranger to seeking redress for wartime actions. He has previously helped survivors of the Chongqing bombing and victims of the notorious germ-warfare detachment, Unit 731. His transition to fighting for cultural restitution stems from a belief that addressing cultural crimes is just as important as addressing human rights violations.

The association faces considerable resistance. They have sent formal requests to the Yasukuni Shrine regarding other looted items, such as Chinese stone lions. Despite multiple petitions and a single meeting in 2023, the shrine has largely stonewalled their efforts, stating there are “no developments to report.” Ichinose remains undeterred, insisting that the issue cannot simply be ignored.

Takakage Fujita, a co-representative of the group, noted that many developed countries which invaded others are gradually returning looted items. He stated that correcting past mistakes is the first step toward reconciliation. The group holds regular meetings and organizes public gatherings to educate the Japanese public. When they started, few Japanese citizens were aware of the looting of Chinese cultural property, but that is slowly changing.

A Global Movement for Restitution

The push for the return of the Tang stele is part of a much larger global trend. Nations around the world are increasingly demanding the return of cultural heritage looted during colonial times and wars. This wave of repatriation is reshaping the relationship between former colonizers and the colonized.

In Egypt, the government has successfully retrieved more than 30,000 artifacts since 2014. Mohamed Ismail Khaled, secretary-general of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, emphasized that these items are essential components of national cultural identity. Recently, Egypt secured the return of a mummified head from the Netherlands after scientific analysis proved its origin.

Similarly, Nigeria has spent decades reclaiming the Benin Bronzes, looted by British forces in 1897. Rev. Anamah N.U.B from Nigeria’s Ministry of Art, Culture, Tourism and the Creative Economy stated that returning these artifacts is about restoring African dignity. Countries like Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom have already returned or committed to returning such items.

Japan, however, shows a comparatively negative attitude toward these movements. Activists like Ichinose believe this reluctance stems from the government’s failure to fully reflect on its history of aggression. While Western institutions often use moral and ethical arguments to justify returns, the Japanese government’s passive attitude suggests a reluctance to address lingering historical injustices. This places Japan at odds with the evolving international consensus on cultural heritage.

The Fight for Cultural Justice

The demand for the stele’s return is deeply intertwined with regional politics. Beijing’s ongoing national campaign to reclaim cultural heritage coincides with rising regional tensions. Disputes over territory, such as the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands, and historical memory, including visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, strain Sino-Japanese relations. The return of the stele is framed by activists as a gesture that could improve ties.

Tong Zeng, president of the China Federation of Demanding Compensation From Japan, has been involved in this fight for years. He submitted the first requests to the Japanese government as far back as 2014 and even wrote to the Emperor in 2019. Despite receiving no response, he continues to work with Japanese scholars and civil groups. He insists his organization is not affiliated with the government, though the political nature of the request is undeniable.

Legal challenges also complicate the process. Huo Zhengxin, a law professor at the China University of Political Science and Law, explained that existing international treaties for pursuing returns were established after World War II. Consequently, they are difficult to apply to actions taken during earlier conflicts like the Russo-Japanese War. Without a strong legal framework, the fight relies on moral pressure, historical evidence, and diplomatic negotiation.

The release of the “Compendium of Archival Documents” aims to bridge the gap left by legal ambiguities. By proving the stele was illegally seized as a war trophy, Chinese researchers hope to force a moral reckoning. The joint declaration serves as a reminder that cultural heritage is not just property, but a vessel of history that belongs to the people who created it.

At a Glance

- Chinese researchers and Japanese activists issued a joint declaration urging Japan to return the Tang Honglu Well Stele.

- The 9.5-tonne stele was erected in 714 AD during the Tang Dynasty and removed from China between 1906 and 1908.

- It was transported to Tokyo as a war trophy following Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War.

- The artifact is currently held in the Fukiage Garden of the Imperial Palace, inaccessible to the public.

- A new book, Compendium of Archival Documents on the Tang Honglu Well Stele, provides evidence to support the claim of illegal seizure.

- Japanese activist group the Chinese Cultural Relics Return Movement Promotion Association is leading efforts within Japan to secure the return.

- The call for restitution is part of a global trend of nations recovering cultural heritage lost during colonial times.