A turning point for the worlds two largest workforces

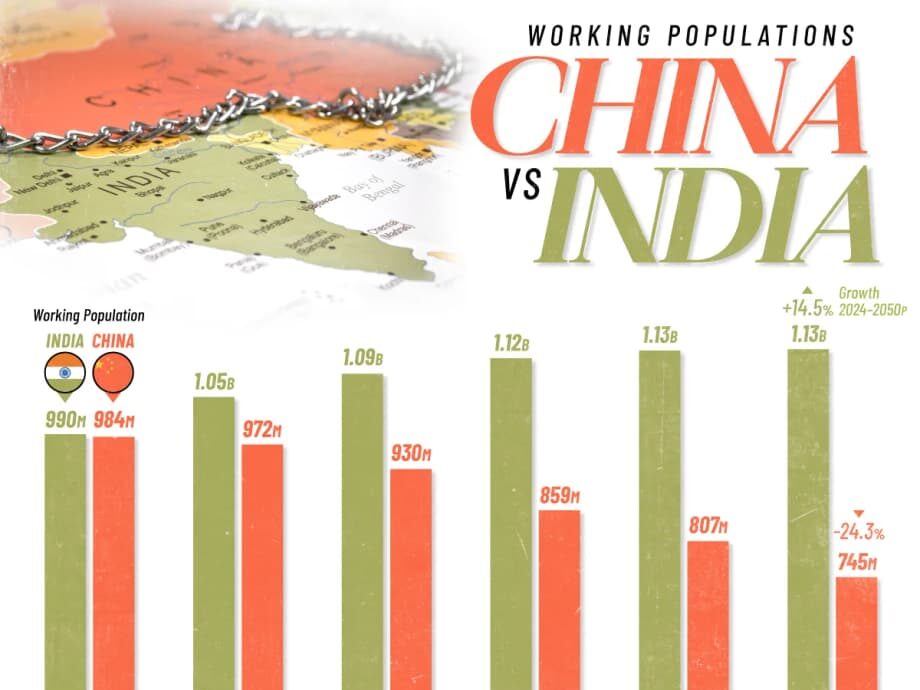

India and China sit at the center of a demographic realignment that will shape the global economy for decades. The two countries still have the largest labor pools on earth, yet their trajectories have split. United Nations projections show that Indias working age population, ages 15 to 64, will expand from about 990 million in 2024 to roughly 1.13 billion by 2050. China will move in the opposite direction, with its working age cohort shrinking from about 984 million to near 745 million over the same period. Those shifts equal a gain of about 144 million potential workers for India and a loss of about 239 million for China. The result will ripple through manufacturing, trade, investment, and national power.

- A turning point for the worlds two largest workforces

- India rises, China grays: the numbers behind the shift

- Who turns a population bulge into a dividend

- Manufacturing, supply chains, and investment shifts

- Social contracts under pressure

- Regional differences inside India and China

- What it means for global power and geopolitics

- How businesses can prepare

- What to Know

This story is about more than headcounts. China is aging quickly and has very low fertility, which raises costs for employers and for the state. India remains younger. It has a rising share of people in their prime working years, yet the benefits are not automatic. Jobs, skills, and healthier lives will determine whether a bigger workforce lifts living standards and growth. The global picture adds context. The worlds working age population is projected to grow by roughly 15 percent by 2050, and India will supply a large share of that rise while China reduces the global total.

What counts as working age and why it matters

Demographers classify working age as 15 to 64 years. It is a simple yardstick, not a guarantee of labor force participation or productivity. The concept matters because it shapes the support ratio, the number of workers relative to dependents, mainly seniors and children. When the support ratio rises during a demographic transition, countries can enjoy a demographic dividend. Growth tends to be stronger when young adults find jobs, gain skills, and save more of their income. When the support ratio falls, the strain on public finances and on younger workers grows. This is where China and India diverge. China is entering a period of falling support ratios and rising care needs. India is still in a phase where it can harvest a dividend if policies align with demographics.

India rises, China grays: the numbers behind the shift

The headline trend is clear. Indias working age population is set to expand by about 14 to 15 percent by midcentury. China is set to contract by roughly one quarter. A falling number of potential workers in China will meet a rising number of retirees. The balance already began to change in the 2010s when Chinas working age cohort peaked. Analysts expect it to drop to roughly 700 million by midcentury. At the same time, Chinas population aged 60 and older could approach 500 million by around 2050, up from about 200 million today. That puts pressure on pensions, health systems, and local finances.

India enters the period from a different place. The country recently became the most populous nation. Its median age is still under 30, and a large share of its citizens are under 25. The United Nations expects Indias working age headcount to keep rising through the 2030s and 2040s, then level off close to 2050. A larger pool of potential workers can boost production and attract capital seeking scale, but only if jobs and skills keep up. Without that match, a larger workforce can face underemployment, informality, or stalled wages.

Fertility, longevity, and the policy legacy

Three forces drive these outcomes: fertility, mortality, and migration. China has a legacy of the one child policy and rapid urbanization. Families have grown smaller as living costs, housing, and education expenses rose. Fertility fell well below the replacement rate years ago and has kept sliding. Policy shifts that encourage two or three children have not reversed the trend. Increased longevity adds to the number of seniors who will need care for longer lives. India is on a different path. Fertility fell quickly over three decades and is now near or slightly below replacement in many states. The north still has higher fertility than the south, and demographic momentum will keep births high for some time because many women are in childbearing years. The mix is uneven across the country, which influences where labor supply will grow the fastest.

Who turns a population bulge into a dividend

Population structure sets the stage. Economic outcomes depend on participation and productivity. That is why a simple headcount of 15 to 64 year olds can mislead. China still has advantages in education quality, skills, and female labor force participation. India has ground to cover on education attainment and health, and many women remain outside the labor market for reasons that include safety, childcare access, social norms, and the structure of available jobs. Closing those gaps can change the trajectory of growth more than the raw population numbers suggest.

Economists who compare the two countries often reweight the workforce by schooling levels and participation. In those comparisons, Chinas smaller workforce could still produce more total output if productivity remains higher. For India to turn a larger working age cohort into faster growth, it will need to expand participation among women and improve learning outcomes in schools, then match those skills to formal sector jobs. The prize is large. If participation and productivity rise together, the demographic dividend becomes a lasting lift to incomes and public revenue.

The role of women in the workforce

Women are the fulcrum of Indias demographic opportunity. Higher female participation raises household income, boosts savings, and supports healthier children. It also enlarges the tax base. Policies that work include safe and reliable transit, flexible work arrangements, childcare, and training that maps to actual jobs. Services and light manufacturing can be strong entry points when employers design roles that support on-ramps for women who are new to the labor market or who return after care breaks. Countries that widen the door for women tend to get a double dividend, more workers and higher productivity per worker.

Manufacturing, supply chains, and investment shifts

A shrinking workforce in China and rising wages have already nudged global supply chains to diversify. Vietnam, Bangladesh, and parts of India have absorbed manufacturing in apparel, electronics assembly, and consumer goods. China still holds unmatched depth in supplier networks, logistics, and skilled technicians, and it is automating quickly to offset labor shortages. Even so, the labor arithmetic is moving. Companies that make goods for global markets want multi country footprints to manage cost, resilience, and policy risk.

India wants a larger slice of the factory floor. The government has marketed production linked incentives, invested in roads and ports, and eased rules in some sectors. Electronics assembly has grown, led by mobile phones, and more components are sourced domestically than a few years ago. The next step is harder. To approach the Lewis turning point, when surplus rural labor shifts into higher productivity industry and services, India must create millions of steady, higher value jobs each year and lift skills at the same pace. Urban infrastructure, power reliability, customs efficiency, and contract enforcement all matter to investors. Automation and artificial intelligence also change the equation. Low cost labor helps, but the winners will be the locations that combine scale with reliability, speed, and skills.

Social contracts under pressure

Aging changes what households buy and what governments must fund. Across the world, seniors will account for a much larger share of total consumption by 2050 than they do today. In countries that are aging fast, including China, the share of working age people in the population will fall through midcentury. Support ratios will decline and retirement systems will face larger gaps. That creates a menu of choices. People can work more years. Productivity can rise faster through technology and better management. Immigration can fill shortages in some sectors. Public and private savings can be retooled to fund care and pensions. No single lever will carry all the weight. Countries that move early on a balanced mix will handle the shift with less disruption.

Regional differences inside India and China

Neither country is uniform. In India, southern and western states have very low fertility and are already aging. Some local leaders have begun to encourage larger families. Northern states, which tend to be poorer and more rural, still have higher fertility and will supply most of the growth in labor supply over the next two decades. That mix magnifies the need for mobility, skilling, and urban jobs. The challenge is to connect workers in the north to growth hubs without straining housing, transit, and water in already crowded cities.

China also faces internal divides. Urban coastal regions are wealthier and older, with better services and more automation. Interior provinces have different labor profiles and fiscal capacity. Policy changes that relax household registration rules could improve mobility, yet the demographic tide will not turn quickly. The number of women in childbearing age cohorts is falling. The cost of raising children is high in cities. Incentives to have more children have had modest effects in other countries and are unlikely to reverse long term trends without deeper shifts in housing, work, and care.

What it means for global power and geopolitics

Demography will shape national power, yet it will not decide outcomes on its own. A smaller Chinese workforce, more retirees, and slower population growth are constraints on military and economic capacity. At the same time, the country remains large, urbanized, and technologically capable. The United States and a network of allies maintain a population and technology base that offsets some of Chinas scale advantage. India will hold a growing share of the global labor pool and can gain influence if it nurtures jobs, education, and health at scale.

Some analysts argue that Chinas demographic clock reduces its room for strategic patience. Others caution against linear predictions. Michael OHanlon, a security scholar, offered a useful reminder about inflated assumptions of Chinese power.

China is not 10 feet tall.

He added that time is not automatically on Beijings side. The broader lesson is to avoid fatalism. Human capital, alliances, innovation, and policy choices will steer outcomes within the boundaries set by demographic math.

How businesses can prepare

Executives do not control fertility trends, but they can plan for their effects. A few moves stand out:

- Diversify manufacturing footprints into more than one country while keeping a strong presence in China for advanced supply networks and in India for scale.

- Invest in automation and training to raise productivity where labor supply is tight, including older worker friendly jobs.

- Design products and services for aging consumers in China and for young urban consumers in India.

- Build talent pipelines in India with partnerships in vocational training and community colleges to raise skills for entry level roles.

- Use remote and distributed work models to tap talent pools in secondary cities.

- Plan for regulatory and policy shifts that support female labor force participation, such as childcare and safe transport, and align hiring practices to capture the benefit.

What to Know

- Indias working age population is projected to rise from about 990 million in 2024 to roughly 1.13 billion by 2050, while Chinas is expected to fall from about 984 million to near 745 million.

- The global working age population could grow by around 15 percent through 2050, with India adding a large share and China reducing the total.

- Chinas working age cohort peaked in the last decade and is projected to decline toward about 700 million by midcentury as the population aged 60 and older approaches roughly 500 million.

- Indias demographic dividend is not automatic. Higher labor force participation by women, better education, and healthier lives will determine how much growth the country can unlock.

- Supply chains are diversifying. China is automating to offset labor shortages, and India is attracting some manufacturing but must create millions of quality jobs each year to sustain momentum.

- Aging will strain public finances in many countries. Support ratios will fall, and funding needs for pensions and care will rise.

- Regional contrasts matter. Southern India is aging quickly, while the north will supply most new workers. China faces urban coastal aging and different pressures in the interior.

- Demography sets constraints but does not fix outcomes. Policy, skills, technology, and alliances will shape how India and China convert people into power.

For primary data and interactive projections, see the United Nations World Population Prospects (2024 revision) at population.un.org/wpp/.