Why so much study brings limited speaking ability

Vietnam has made learning English a national priority for decades. Millions of students attend several English periods a week from early grades and many families pay for extra classes. Yet a familiar pattern persists. After years of study, large numbers of learners still hesitate to speak, struggle to catch fast speech, and mispronounce common words. The country’s 2024 EF English Proficiency Index score placed Vietnam 63rd out of 116 countries, a low proficiency tier, despite steady investment and growing enthusiasm. At the same time, the government has set a bold goal to make English a second language in schools by 2035, and to start compulsory English from grade one by 2030. That vision, while inspiring, collides with shortfalls in teacher supply, uneven training, and an exam culture that prizes test strategies over confident communication.

- Why so much study brings limited speaking ability

- How English is taught in Vietnamese schools

- What holds learners back in practice

- Teachers carry the system on their backs

- English medium instruction expands, brings fresh challenges

- What works for learners, teachers, and parents

- Policy choices on the horizon

- Key Points

The paradox is stark. Students often sit through far more classroom hours than international guidelines suggest for intermediate proficiency, yet many cannot use English comfortably outside school. In Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi, English centers have multiplied rapidly, and course fees can absorb a large share of a worker’s monthly income. Families are sacrificing for a skill that promises opportunity. Evidence shows the barrier is not ability. It is approach, habit, and environment. That is why a story many Vietnamese teachers know resonates: a British instructor who learned Vietnamese to near-native fluency. Vietnamese is daunting for foreigners, yet he succeeded through daily practice, immersion, and attention to culture. His progress did not come from talent alone. It came from a method that prioritizes use, feedback, and steady exposure, the same ingredients Vietnamese learners need in English.

How English is taught in Vietnamese schools

English entered public schools as a compulsory subject in the 1980s. Today, primary students often have four 45 minute English periods per week, and secondary and high school students have three. A large share of students study English for 10 years or more. The national goal for many programs is Level 3 on Vietnam’s six level framework, equivalent to B1 in the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). B1 indicates independent use of English for everyday communication.

Cambridge Assessment estimates that B1 requires about 350 to 400 guided learning hours. These are structured hours focused on achieving specific learning goals, often including targeted practice beyond the classroom. Vietnamese students frequently spend much more time than that in school lessons, yet outcomes lag. One reason is the difference between seat time and guided practice. Repetition without real communication does not create the automatic reflexes that conversation demands. Another reason is spacing. Lessons typically occur on non consecutive days, which weakens memory consolidation between classes.

Associate Professor Le Van Canh, a veteran teacher educator in Hanoi, has warned that lesson spacing works against retention when practice is too infrequent.

Le Van Canh said that with one to two days between lessons, students forget about half of what they learned before it can move from short term to long term memory.

Assessment steers classroom behavior

Eight years of national high school exam data show that a majority of candidates score below average in English, while the share of students exempted from the test through international certificates remains small. When university admission hinges on test scores, schools and private centers optimize for exam tactics. That often means grammar translation, gap fills, and predictable listening items. Speaking and spontaneous listening get less time because they are harder to grade quickly and less rewarded by high stakes exams. Imported textbooks and methods can help, yet many are not tuned to local class sizes, learner profiles, or teacher training realities. A heavy focus on tests narrows what happens in class and turns English into a subject to pass rather than a tool to use.

What holds learners back in practice

Research with Vietnamese learners points to recurring obstacles. Students cite limited vocabulary, difficulty producing new sentences without scripting, pronunciation issues that blur meaning, few chances to speak outside class, fear of making mistakes, and large classes that limit individual practice. The classroom environment often pushes accuracy before fluency. There are cultural factors too. Many learners worry about losing face when corrected. Together, these pressures restrict the very risk taking that builds conversational confidence.

Language transfer and pronunciation hurdles

Vietnamese and English differ strongly in grammar and sound systems. That gap creates predictable errors that can persist for years unless addressed explicitly. Vietnamese has no articles, so learners omit a and the. The verb to be is often dropped with adjectives, leading to He hungry instead of He is hungry. English tense marking can be confusing because Vietnamese relies more on time words rather than verb changes, so learners avoid complex tenses even when they understand them in drills.

Pronunciation challenges are equally clear. Vietnamese has no final consonant clusters, so learners often delete final sounds like s, z, t, v, or ks. Losing those endings can confuse listeners because English uses final sounds to mark grammar (cats versus cat) and to differentiate words (rice versus ride). Many learners substitute r and l with other sounds, and the English th often turns into t or d. English is stress timed and relies on longer vowels for meaning contrasts, while Vietnamese does not have the same long vowel contrasts. The result is that even strong grammar knowledge may not convert to intelligible speech without focused pronunciation work.

Speaking anxiety and fear of mistakes

Plenty of Vietnamese students know the rule but avoid using it in conversation because they worry about being wrong. Studies on Vietnamese learners report shyness, fear of making mistakes, and low motivation when practice does not feel meaningful. A recent validation study of a Vietnamese scale for self regulated motivation in speaking found that learners who regulate emotions and work with peers tend to score higher in speaking. The same study noted that managing the learning environment is less common, likely because many students have limited access to authentic speaking situations. That gap reinforces the anxiety cycle. Without real interaction, confidence does not grow. Without confidence, students practice less.

Too little real use beyond class

Many students revert to Vietnamese as soon as class ends. English clubs are limited or irregular, and large classes reduce opportunities to speak one on one with a teacher. Native speaking teachers are unevenly distributed, with urban centers attracting talent and rural schools struggling to recruit. Several surveys also note that learners have few places to practice English casually, such as community groups, online conversation hours, or campus wide English zones. When English remains confined to the classroom, gains fade between lessons.

Teachers carry the system on their backs

Vietnam faces a shortfall of English teachers just as the country moves to start compulsory English from the first year of primary school. Many public schools cannot match private center salaries, so recruiting and retention are hard. Some teachers handle dozens of classes a week, leaving little time for lesson planning, feedback, or professional development. Authorities estimate that thousands more English teachers will be needed at preschool and primary levels by 2030, and a large number of current teachers require retraining to meet updated standards.

Nguyen Thi Binh Minh, principal of Thang Long Primary School in Hanoi, captured the dilemma facing school leaders.

Minh said she is excited to give children earlier access to English but worried about recruiting enough qualified teachers, since many shift to higher paying jobs at private centers.

Training, not just hiring

Strong English alone does not make a strong teacher. Methods matter. Many current teachers grew up in a system that prized reading, writing, spelling, and grammar. They are often less confident leading fluency tasks, spontaneous listening practice, or pronunciation drills. Imported programs can misfire if they assume smaller classes, different student backgrounds, or more teaching aids than local budgets allow. Teacher training needs to capture the daily realities in Vietnamese classrooms, from managing large groups to building a culture that welcomes mistakes as a natural part of learning. Better pay, clear career pathways, and extra support for rural posts would help keep talent in public schools. So would a national mentoring network that pairs new teachers with experienced coaches and gives them time to observe, practice, and reflect.

English medium instruction expands, brings fresh challenges

Universities across Vietnam are expanding English medium instruction to attract international partners and raise graduate competitiveness. The trend mirrors global growth. Many institutions now teach selected majors partly or fully in English. This shift has promise. It also exposes weaknesses when students and lecturers are not fully ready.

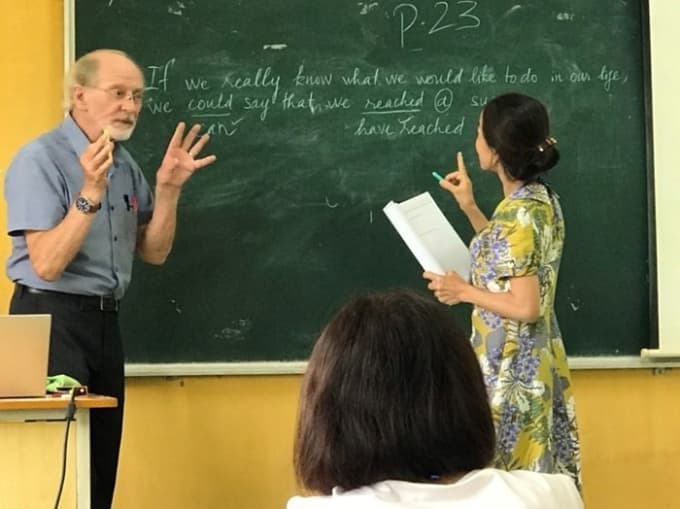

At a recent conference in Ho Chi Minh City, Dr. Gary Bonar of Monash University summarized the risks he has seen across countries.

Bonar said the first and greatest challenge is uncontrolled expansion, where institutions adopt English medium programs without the infrastructure or staff development to support them.

He also described role confusion when lecturers see themselves only as content experts and do not support language development, and the pressure of promotion systems that reward research output more than teaching quality. Even lecturers with strong English can struggle to improvise in fast moving classroom exchanges if they have not taught in English before. Many are placed into English medium courses without methodological training and must develop a new professional identity that blends content teaching and language support.

Technology can help if it is tied to good design. Dr. Greg Kessler of Ohio University argued that digital tools can create more interaction and personalization.

Kessler said he can envision every student having an AI tutor and every teacher having an AI teaching assistant, supported by tools like virtual reality, gamification, and digital storytelling.

These ideas can lower barriers to practice and give students more feedback, yet they cannot replace the need for trained lecturers, realistic workloads, and clear policies that protect teaching quality.

What works for learners, teachers, and parents

Vietnamese learners do not lack talent. They need daily exposure, meaningful use, and permission to make mistakes. The British instructor who mastered Vietnamese did not wait for perfect grammar before speaking. He listened a lot, spoke daily, and used Vietnamese to connect with people and understand their lives. That approach builds both fluency and motivation. Research in Vietnam shows that when students set clear goals, regulate emotions, and work with peers, their speaking scores improve. The key is to turn English from a subject into a habit.

For students

- Make English a daily ritual. Aim for 20 to 30 minutes of listening and 5 to 10 minutes of speaking every day.

- Shadow short clips. Repeat after clear speakers, copy stress and rhythm, and record yourself to compare.

- Grow vocabulary in topics you care about. Learn words in chunks, like take a break or make a decision, then use them in messages or short voice notes.

- Join or start an English club. If your school lacks one, create a weekly conversation hour with three or four friends and simple rotating roles.

- Use self regulated strategies. Remind yourself why speaking matters for your goals, manage anxiety with breathing or short warm ups, and practice with classmates who support you.

- Set small speaking goals. For example, ask two questions in English in every class, or tell a one minute story about your day.

- Mix media. Alternate short podcasts, songs with lyrics, and scenes from films with subtitles, then retell what you heard in your own words.

- Try structured online exchanges with peers from other countries when available, and use AI speaking tools for extra practice, then get human feedback from a teacher or friend.

For parents

- Value communication, not just perfect grammar. Praise effort and courage to speak.

- Create exposure at home. Set English story time, watch cartoons with subtitles, and play simple word games.

- Protect the Vietnamese foundation. Rich vocabulary in the mother tongue supports thinking and learning in any subject, including English.

- Choose programs that promise speaking practice in every lesson. Ask how many minutes your child will speak per class and how pronunciation is taught.

- Resist chasing scores only. A fast rise in test marks can hide weak listening and speaking skills.

- Support routines. Short, daily practice beats long, irregular sessions.

For teachers and schools

- Make time for speaking in every class. Use pair work and rotating roles so every student talks.

- Teach pronunciation as a class activity. Focus on final sounds, consonant clusters, th, and long versus short vowels. Use fun drills and group correction to reduce fear.

- Integrate listening with transcripts. Let students notice connected speech, then read aloud with correct rhythm.

- Build a culture that accepts mistakes. Set a clear rule that errors are welcome during speaking tasks, then target correction afterward.

- Use spaced retrieval. Recycle key language across weeks with quick reviews so gains stick.

- Track speaking time. Aim for a minimum number of minutes per student per class, even in large groups.

- Create English zones during breaks or at clubs. Recruit near peer mentors, such as older students, to lead small group chats.

- Pilot small English medium modules only where support exists. Provide lecturer training, lighter teaching loads, and language support for students.

- Leverage technology sensibly. Use AI for pronunciation feedback and extra listening, then discuss output together to avoid fossilizing errors.

Policy makers can back these shifts with targeted moves: raise compensation and rural bonuses for English teachers, fund mentoring time within the work week, build a national bank of graded listening and reading materials aligned to CEFR, and sponsor university speaking clinics that offer free conversation hours to nearby schools. When schools teach young children, keep it playful with songs, stories, and physical activities, and avoid heavy grammar drills. Growth comes from use and enjoyment at that age, not memorization.

Policy choices on the horizon

The Ministry of Education and Training has outlined a multi phase plan to make English a second language in schools by 2035, broaden English in preschool by the early 2030s, and expand English medium instruction through higher education. The Politburo has endorsed comprehensive education reform that includes stronger foreign language learning. Achieving these goals will require time, resources, and local tailoring. Many experts caution that making English a second language across 50,000 public schools will not happen quickly, especially with current teacher shortages and uneven infrastructure.

Le Van Canh has urged patience and realism.

He said it could take decades with a clear roadmap and strong strategies to make English a second language in schools, and that success depends on helping learners use English effectively for social communication, not chasing native like targets.

Some scholars also warn against pushing English before a strong base in the mother tongue.

Dr. Ngo Tuyet Mai said that teaching English to children without first strengthening Vietnamese is like building a house on weak foundations.

The policy picture is not just about adding more English. It is about better English. A roadmap that phases in teacher training, aligns exams with communicative goals, supports poorer provinces, and uses technology to widen access will matter more than slogans. Early grades need play based exposure. Secondary and university levels need meaningful speaking and listening targets tied to CEFR, plus support for lecturers who teach through English. Parents and students are already investing. With the right method and daily practice, the years spent on English can finally turn into confident voices.

Key Points

- Vietnam has expanded English teaching for decades, yet the 2024 EF index ranked the country 63rd of 116 with low proficiency.

- Students often study English for a decade or more, but exam oriented teaching and infrequent practice limit speaking and listening gains.

- B1 proficiency requires roughly 350 to 400 guided hours, less than many Vietnamese students already spend, showing quality matters more than time.

- Common hurdles include missing articles and the verb to be, tense avoidance, final sound deletion, and difficulty with th, r, and l.

- Fear of mistakes and few real life opportunities to speak reduce confidence and slow progress.

- Teacher shortages are acute, with public schools struggling to recruit and retain English teachers compared with private centers.

- English medium instruction is expanding, but experts warn about uncontrolled growth without training, resources, and realistic workloads.

- Research in Vietnam links self regulated motivation and peer collaboration with better speaking scores.

- Daily exposure, fun pronunciation work, pair speaking, and a classroom culture that welcomes errors make a measurable difference.

- Government plans to make English a second language by 2035 will require long term investment, teacher development, and locally adapted curricula.