A scheme built on debt and fear

South Korean police say they have dismantled a loan racket that preyed on foreign workers with sky high interest and aggressive collection tactics. Investigators in Busan allege a Korean father and son ran an unregistered lending network that issued small loans to thousands of migrant workers, then charged up to 154 percent interest a year. The ring extended about 16.2 billion won (about S$14.3 million) in credit to at least 9,120 borrowers since early 2022, generating an estimated 5.5 billion won in illicit profits.

- A scheme built on debt and fear

- How did the ring exploit migrant workers

- What the law says and why 154 percent interest is illegal

- Interpol request and the cross border manhunt

- Debt, coercion and migrant labor risks

- Are authorities moving to protect workers

- What victims can do right now

- What happens next in the case

- Key Points

According to the Busan Metropolitan Police Agency, the alleged mastermind is a 60 year old Korean national who has been living in Thailand. Officers say he directed the operation from abroad and recruited brokers through social media, posing as the operator of a language academy to present a veneer of legitimacy. His 30 year old son is accused of managing contracts and collections inside South Korea. Police have arrested several suspects, referred six people for prosecution, and requested that Interpol issue a Red Notice for the father, who left Korea in 2020 while under scrutiny in a previous case.

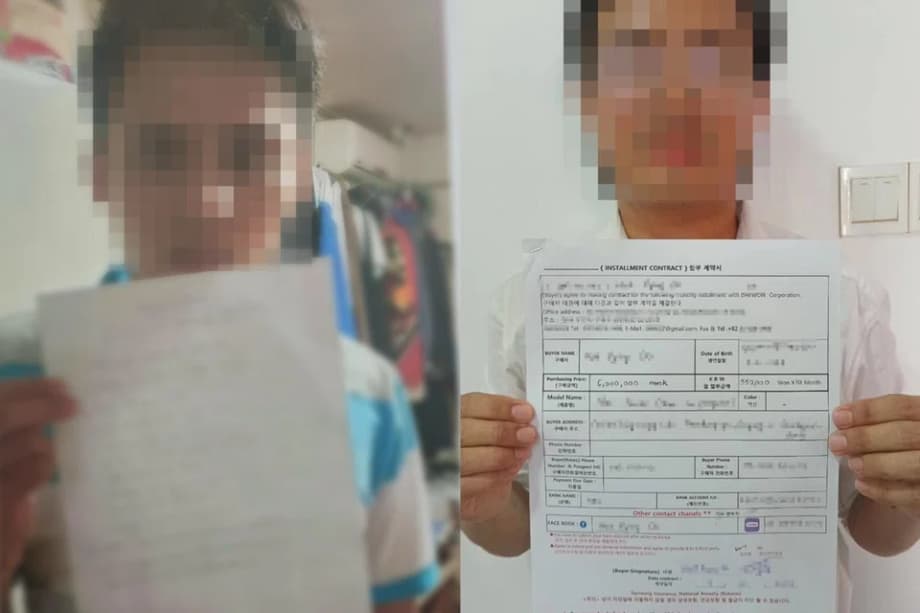

Victims typically borrowed between 1 million and 5 million won to cover urgent living costs, remittances, medical bills, or fees tied to their employment. Most were men from Southeast Asia in their 20s to 50s, people who often face language barriers and limited access to formal banking. When borrowers missed payments, the group reportedly sent letters claiming to seize assets, warned that wages and pensions were at risk, and threatened to report workers to immigration authorities. The ring also disguised loans as sales contracts by fabricating installment purchase agreements, then filed more than 1,500 court claims worth over 5 billion won to cement a legal advantage.

The investigation began in April after intelligence pointed to illegal lending focused on migrants. Officers carried out search and seizure operations, tracing repayments and identifying thousands of victims. Authorities say they have frozen about 2.1 billion won in suspected criminal proceeds and notified the tax office to pursue unpaid taxes tied to the illegal income. Police say the search for the alleged ringleader is ongoing.

How did the ring exploit migrant workers

Many migrant workers in South Korea struggle to access affordable credit. Employers typically sponsor work permits, but new arrivals can lack a credit history, collateral, or the documents banks require. Language barriers and long shifts make it difficult to navigate account opening and consumer finance. Some live in factory dorms or rural areas with limited support services. In that gap, informal lenders and brokers promise instant cash with minimal paperwork. The risks are enormous when borrowers cannot keep up with payments.

Investigators say the group built a pipeline to reach workers where they gather online. The father allegedly set up a fake language academy as a front, then recruited brokers through social media. Those brokers connected loan seekers to the organization and relayed paperwork. Marketing pitches promised quick approval, flexible terms, and help in languages workers understand. The model relied on volume and speed. Once loans were extended, the pressure to pay began almost immediately.

Behind the scenes, the network maintained the appearance of legality by fabricating installment purchase contracts, which make a transaction look like a sale rather than a loan. When borrowers fell behind, collectors sent legalistic notices and then filed court claims based on the fake contracts. The letters also carried threats that hit migrants hardest, such as warnings about immigration trouble and wage seizure. Faced with the fear of detention or deportation and unclear about their rights, many workers paid whatever they could to make the problem go away.

What the law says and why 154 percent interest is illegal

South Korea regulates private lending under the Registration of Credit Business and Protection of Finance Users Act. Moneylenders must register, follow disclosure rules, and abide by an interest rate ceiling. In recent years policymakers lowered the cap to 20 percent a year to protect consumers from predatory lending. A rate of 154 percent far exceeds the legal ceiling. Running a loan business without registration and extracting excessive interest can trigger criminal charges, civil liability, and the forfeiture of profits.

The alleged ploy to rename loans as sales does not shield lenders from the law. Courts can look through form to substance, and agreements crafted to evade licensing and rate caps can be deemed void, fraudulent, or both. By filing more than 1,500 small claims based on fabricated sales contracts, the ring tried to convert unlawful debts into court backed obligations. Migrant borrowers may not receive notices in their language or may be too afraid to respond, which can result in default judgments that deepen the debt spiral.

Workers can reduce risk by checking whether a lender is registered with financial regulators and by seeking help from local support centers before signing any contract. Warning signs include requests to hand over passports, unexplained fees, interest quoted per week rather than per year, and pressure to sign documents that do not match the actual transaction. A legitimate lender will not threaten to contact immigration authorities over a consumer debt.

Interpol request and the cross border manhunt

Police have asked Interpol to circulate a Red Notice for the alleged ringleader in Thailand. A Red Notice is not an international arrest warrant. It is a request to locate and provisionally detain a wanted person pending extradition or similar legal action. Local authorities decide whether to arrest, based on domestic law and any applicable treaty. Interpol describes Red Notices on its website, which explains that the notices share identity details, photographs, and the charges sought by the requesting country. For reference, see Interpol’s overview of Red Notices at this link.

In practical terms, the request signals that South Korean authorities plan to pursue the case across borders, working with Thai counterparts through mutual legal assistance channels. Bank records, messaging app data, and money transfers tied to collection activity inside Korea could be central to tracing responsibility. If the suspect is detained abroad, courts will weigh the charges and the evidence before deciding on extradition.

Debt, coercion and migrant labor risks

Debt can be a powerful tool of control in low wage labor markets. Research on migrant worker exploitation shows that many people take on heavy debts before departure to cover recruitment, transport, or training. Once abroad, emergency costs or wage delays can pile on even more borrowing. When lenders rely on intimidation, threats, and legal tricks, debt becomes a lever to coerce repayment regardless of fairness or legality. That is why police view interest far above the legal cap and false court filings as red flags for exploitation.

South Korea’s 2023 Trafficking in Persons report from the United States government described challenges in identifying labor trafficking victims and in separating trafficking from other crimes. The report noted that debt based coercion, document confiscation, and retaliation threats are common tactics used against migrant workers in sectors such as fishing, agriculture, and manufacturing. Many victims fear contacting authorities or are unsure how to access services without risking their status. The intimidation described in the Busan case, especially threats to report workers to immigration, mirrors methods seen in forced labor situations, even if each case must be judged on its facts.

Global research bodies have documented how recruitment fees, deceptive contracts, and illegal loans trap migrants in cycles of repayment. One study urged governments to ban worker paid recruitment fees, expand legal aid, and increase transparency in the hiring chain. Access to fair credit matters because an emergency loan should not become a path into coercion. When legal, affordable alternatives are available, the appeal of predatory lenders shrinks.

Are authorities moving to protect workers

South Korean agencies have expanded their focus on worker protection in recent years. A national trafficking specific hotline was launched, and a policy coordination council was created to align government action. Prosecutors and police have brought cases using the credit business registration law and fraud statutes. While the Busan case involves alleged organized moneylending rather than a workplace abuse setting, successful prosecution would signal that exploiting migrants through illegal finance will be met with criminal penalties and asset seizures.

Origin countries are also stepping in. The Philippines Department of Migrant Workers says it is pursuing brokers who charge improper placement fees for seasonal jobs in South Korea, a practice that pushed some workers to borrow from lenders and hand over months of wages. The agency reports dozens of pending cases and a shift to tighter review of contracts, insurance, and worker welfare. Reducing illegal fees up front can lower the risk that people fall into dangerous debt later.

Indonesia has introduced a financing scheme for prospective migrants through People’s Business Credit, allowing loans up to 100 million rupiah without collateral to cover placement costs, training, and living expenses until first paychecks arrive. Officials say the program makes funding transparent and reduces reliance on unlicensed lenders. Measures like these, paired with better access to banking in destination countries, can cut off the oxygen to predatory networks.

What victims can do right now

Victims of illegal lending should know that help is available, and reporting a crime does not automatically lead to immigration penalties. Police and support centers can connect workers to interpreters and legal aid. If you or someone you know has been caught in a similar scheme, consider the following steps.

- Keep every document, message, and payment record. Screenshots of chats and bank transfers help investigators trace the scheme.

- Do not hand over your passport or alien registration card to a lender or broker. If someone is holding your identity documents, contact the police.

- Check whether a lender is registered. Unregistered lenders and interest above 20 percent a year are warning signs.

- Seek help from a migrant support center, labor office, or your embassy. Ask for a translator if needed.

- If a court notice arrives based on a contract you do not understand, get legal advice rather than ignoring the letter. There may be a way to contest a default judgment.

- If you are Filipino, contact the Department of Migrant Workers or OWWA for assistance. If you are Indonesian, contact KP2MI. Workers of other nationalities can reach out to their embassies in Seoul.

- Avoid lenders who demand fees up front or threaten to contact immigration over a consumer debt. Those are hallmarks of illegal activity.

What happens next in the case

Prosecutors will review the evidence gathered by the Busan police and decide on formal charges for those already detained. The case may include counts related to unregistered credit business operations, fraud involving fabricated sales agreements, and intimidation tied to collection tactics. Courts can order the forfeiture of criminal proceeds and may direct restitution to victims if profits are traced to unlawful lending. The seizure of about 2.1 billion won in assets indicates that financial recovery is on the table.

Internationally, attention will focus on the request to locate the alleged ringleader abroad. If the suspect is detained, courts in the relevant country will assess extradition based on the charges and the evidence. Whether or not extradition proceeds, the digital and financial records collected in Korea are likely to be central to any trial of accomplices. Police have signaled that they plan to continue identifying victims and widening the investigation as new evidence appears.

Key Points

- Police in Busan say they dismantled an unregistered loan ring that lent 16.2 billion won to at least 9,120 migrant workers at rates up to 154 percent a year.

- Six suspects were referred for prosecution. The alleged ringleader, a 60 year old Korean in Thailand, is the subject of an Interpol Red Notice request.

- Victims, mostly men from Southeast Asia, typically borrowed 1 million to 5 million won for urgent needs and faced threats tied to immigration and wage seizure when payments lapsed.

- The group allegedly disguised loans as sales contracts using fabricated installment purchase agreements and then filed more than 1,500 court claims worth over 5 billion won.

- Authorities have frozen about 2.1 billion won in suspected criminal proceeds and alerted tax officials to recover taxes on illegal income.

- South Korea caps private loan interest at 20 percent and requires lenders to register. Running an unlicensed credit business can trigger criminal penalties.

- Debt based coercion is a known risk for migrant workers. Officials in origin countries, including the Philippines and Indonesia, are acting to reduce illegal fees and expand fair credit.

- Victims are urged to keep records, avoid surrendering passports, verify lender registration, and seek help from police, migrant centers, and embassies.