A case that spans borders and years

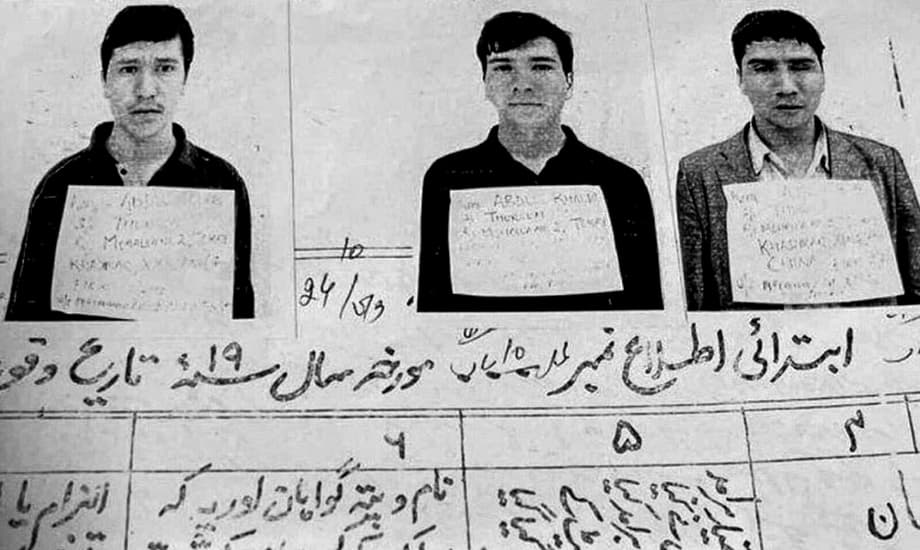

They set out for safety and found a prison cell. In June 2013, three brothers from China’s Xinjiang region, Adil, Abdul Khaliq, and Salamu Tursun, crossed a high mountain border into Ladakh after a grueling journey on foot. They were fleeing persecution that had engulfed Uyghur communities back home. Indian soldiers arrested them near Sultan Chusku, a remote desert stretch in Ladakh, and handed them to local authorities. A court eventually convicted the men of illegal entry and sentenced them to 18 months in jail. That should have ended their story. Instead, it became the beginning of a detention without a clear end date.

- A case that spans borders and years

- A flight for survival across the mountains

- From short sentence to years behind bars

- What the Uyghurs are fleeing

- Life inside prison: language, faith, and health

- Non refoulement and India’s legal duties

- India’s refugee gap and a double standard debate

- Geopolitics at the border: a sensitive file for New Delhi

- Can a third country provide a way out

- What happens if they are sent back

- What a fair resolution could look like

- What to Know

After completing their sentence, the brothers were not released. Officials invoked a preventive detention statute that allows confinement without trial for extended periods. Orders were renewed again and again. More than a decade later, the three men remain behind bars, separated from one another, most recently held in a prison in Karnal in the northern state of Haryana. Their lawyer has fought for their release for years, warning that any deportation to China would expose them to severe harm. The brothers say they only wanted a place where they could live openly as Uyghur Muslims without fear.

A flight for survival across the mountains

The Tursun brothers grew up near Kashgar, a historic city in Xinjiang that sits along the old Silk Road. By the early 2010s, life for many Uyghurs had changed sharply. Mass surveillance expanded. Travel and religious practice drew suspicion. Police checkpoints multiplied. Families described relatives disappearing into detention centers, with little or no explanation. The brothers say they left after relatives were taken and pressure mounted on their own daily lives.

They trekked for nearly two weeks across arid high-altitude terrain where navigation is treacherous and weather is unforgiving. Border lines are not clearly marked in parts of Ladakh, and the region remains tense given long-standing disputes between India and China. When Indian forces encountered the brothers, officials treated the incident as an illegal crossing. The men carried little more than maps and basic tools for survival. They did not speak local languages and could not navigate the legal maze that followed.

From short sentence to years behind bars

A court found the brothers guilty of unlawful entry and possession of knives and maps. The judge imposed an 18 month sentence. During that time the men gradually picked up words in Kashmiri and Hindi, later adding English. They expected to be freed when their term ended. Instead, authorities applied a special public order law and kept them in custody.

What is the Public Safety Act

The Public Safety Act in the former state of Jammu and Kashmir is a preventive detention law. Officials can use it to detain a person without trial for months, and in some cases up to two years, on grounds of security or public order. In practice, detainees can face back-to-back orders that extend confinement for much longer. Access to legal counsel and family can be restricted, and detainees may be moved between prisons, sometimes far from where they were arrested.

For the Tursun brothers, detention orders were renewed repeatedly. They were moved among facilities in Jammu and Kashmir and later taken to Karnal in Haryana, hundreds of kilometers away. The brothers are separated and share cramped cells with people convicted of serious crimes. Their lawyer has petitioned courts, arguing the law was never meant to warehouse refugees who pose no threat and who face clear danger if returned to China.

What the Uyghurs are fleeing

Xinjiang is home to more than eleven million Uyghurs, a mostly Muslim, Turkic-speaking community. Over recent years, the region has seen mass detentions, intense digital and physical surveillance, restrictions on religious practice, family separations, and reports of forced labor. Researchers have identified extensive networks of facilities that held or continue to hold large numbers of people. Former detainees describe rigid indoctrination, punishment for routine expressions of faith, and physical and sexual abuse.

Governments including the United States have said the campaign amounts to genocide. A United Nations assessment found that human rights violations in Xinjiang may constitute crimes against humanity. Beijing rejects these allegations, saying its measures are aimed at countering terrorism and extremism and that the programs have delivered stability and development. Independent verification remains difficult because access to the region is tightly controlled. For Uyghurs who leave, the fear is simple: a forced return could mean immediate detention, prosecution on state security grounds, and long prison terms, particularly for anyone suspected of contact with foreign groups or religious study abroad.

Life inside prison: language, faith, and health

The brothers have adapted as best they can. They learned Kashmiri, Hindi, Urdu, and English during long months on the inside. They keep to their daily prayers. Food is a struggle. Family members and former inmates say the diet is poor, medical care sparse, and hot summers in the plains have been punishing for men who grew up on the high plateau. Two of the brothers developed health problems that worsened over time. Their lawyer says requests for specialized treatment have met delays and denials.

Muhammad Shafi Lassu, the attorney who has represented them for years, says their case is a moral test as well as a legal one. He argues that refugees should not be managed with a public order tool designed for violent offenders.

They are victims of brutality, not criminals. Their only act was to seek safety. India should offer them protection and a chance at asylum, not deportation, said Muhammad Shafi Lassu, the brothers’ lawyer.

Supporters point out that India has hosted tens of thousands of people who fled oppression in Tibet and gave them space to live and work in places like Dharamshala. They ask why the same spirit cannot apply to Uyghurs who face clear danger if sent back.

Non refoulement and India’s legal duties

India is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention. That gap often leaves asylum seekers navigating a patchwork of policies. Even so, international law still binds states to the principle of non refoulement, the rule that no person may be returned to a place where they face a real risk of torture, cruel or inhuman treatment, or other irreparable harm. This safeguard exists in customary international law and has been recognized by the United Nations Human Rights Committee as part of obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which India is a party.

How non refoulement applies

The record from Xinjiang points to severe and ongoing abuses. People who leave China without authorization and who are later accused of ties to separatism or foreign groups face a high likelihood of punishment. In those circumstances, pushing refugees back would violate the prohibition on returning someone to danger. Indian courts have at times acknowledged that constitutional protections, including the right to life and personal liberty, extend to all persons on Indian soil, citizens and non citizens alike. In practice, outcomes have varied, especially in cases involving border security or contested identities.

The brothers’ petitions argue that any deportation to China would breach India’s commitments under international human rights law. They also argue that preventive detention without trial is improper in a case where the original offense was a nonviolent border crossing by men fleeing persecution.

India’s refugee gap and a double standard debate

India does not have a national refugee law. In the absence of a clear framework, asylum seekers rely on ad hoc administrative decisions and, in some cities, screening by the United Nations refugee agency. People intercepted at sensitive borders, including Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir, often do not gain access to that process. Critics say this produces inconsistent outcomes influenced by politics and security concerns more than by protection needs.

They also point to a perceived double standard. India has hosted large Tibetan communities for decades and allowed them to organize cultural and religious institutions. Uyghur arrivals, by contrast, are few and often end up in detention. Advocates link the difference to fear of Chinese pressure and to domestic politics in which Muslim minorities face growing hostility. The debate intensified after the passage of a citizenship law that fast tracks naturalization for certain persecuted groups but excludes Muslims. Officials deny discriminatory intent and say security must come first.

Geopolitics at the border: a sensitive file for New Delhi

The brothers crossed in a region that has seen repeated India China standoffs. Since 2013, the two sides have traded accusations of incursions across their disputed frontier. In 2020, a deadly clash in the Galwan Valley plunged ties to a historic low, with both militaries reinforcing positions along the Line of Actual Control. New Delhi has sought to harden its position while managing a complex relationship with a powerful neighbor. Decisions about Uyghur refugees sit in that shadow, touching on national security, diplomacy, and public opinion.

Officials worry that accepting Uyghur asylum seekers could become a flashpoint with Beijing. At the same time, detaining refugees indefinitely draws criticism from human rights groups and adds to legal pressure at home and abroad. The balance is difficult. The brothers’ case captures how national security instincts can collide with international duties and humanitarian concerns.

Can a third country provide a way out

The brothers have explored resettlement elsewhere. Their lawyer has said he would seek release through India’s Supreme Court if a safe country were willing to accept them. Canada has announced a plan to admit a significant number of Uyghur and other Turkic refugees for resettlement. Activists and community groups have tried to connect the brothers to that channel. Previous appeals to several governments yielded little progress, but advocates say the window remains open if authorities in India allow a transfer.

The United Nations refugee agency has indicated that Uyghurs who can be recognized as refugees should receive protection. India’s practice often distinguishes between groups with long established presences, such as Tibetans, and those caught at sensitive borders. Granting the brothers access to refugee status determination and to a third country resettlement process would align India with non refoulement and reduce diplomatic friction. Their lawyer says a concrete offer from abroad could unlock a legal pathway to freedom.

What happens if they are sent back

Uyghurs returned to China have frequently disappeared into custody. Some have reappeared years later in court records or family notices after trials on state security charges. Reports from across Asia describe cases where Uyghurs were detained and repatriated despite warnings from rights groups and United Nations bodies. A forced return for the brothers would likely mean immediate detention, interrogations about foreign contacts, and possible long prison terms.

Beyond the personal cost, such an outcome would draw scrutiny of India’s human rights record and complicate a government effort to present the country as a responsible regional leader. It would also send a stark message to other persecuted people who reach India’s borders. Legal scholars say there is a workable alternative: acknowledge the men as refugees or, at minimum, protect them from return while a third country resettlement plan proceeds.

What a fair resolution could look like

A resolution does not require a new treaty. It requires steps that Indian institutions already have the tools to take. Authorities can end the use of preventive detention for the brothers, allow access to a refugee screening process, and, if needed, grant supervised release while a third country evaluates resettlement. Courts can weigh the non refoulement rule and the right to life against security concerns that have not been linked to any violent act by the men themselves.

The brothers’ journey began with a decision to flee danger. A rights respecting end would let them live openly and lawfully, either under protection in India or in a country ready to take them in. Their case has become a measure of how the region treats those who cross mountains not to do harm, but to survive.

What to Know

- Three Uyghur brothers from Xinjiang crossed into India in June 2013 and were arrested near Sultan Chusku in Ladakh.

- A court sentenced them to 18 months for illegal entry, but they remained in custody under a preventive detention law.

- Detention orders were renewed repeatedly, and the brothers were moved among prisons, most recently in Karnal, Haryana.

- Their lawyer argues they are refugees fleeing persecution and that deporting them to China would violate non refoulement.

- Uyghurs face mass detention, surveillance, and severe rights abuses in Xinjiang, according to governments and UN assessments.

- India is not party to the Refugee Convention but is bound by non refoulement through other human rights obligations.

- Critics say India treats Tibetan and Uyghur refugees differently, reflecting politics and security concerns.

- A third country resettlement offer could open a legal route for their release if Indian authorities allow the transfer.