A window into Ryukyu’s tributary world

A 1629 imperial edict from the Ming dynasty, recently re exhibited at the Lushun Museum in Dalian, puts a vivid historical spotlight on the Ryukyu Kingdom. The document confirms the succession of a new king, affirms Ryukyu’s participation in the Chinese tributary system, and preserves the language China used to describe a smaller neighbor during a time of shifting power at sea.

- A window into Ryukyu’s tributary world

- What the edict granted and how investiture worked

- Ryukyu in the tributary system of East Asia

- Between China and Japan, a complex balancing act

- What the language and symbols tell us

- The exhibit and the debate it touches

- Why the 1629 edict still informs current research

- Short timeline and key figures

- Highlights

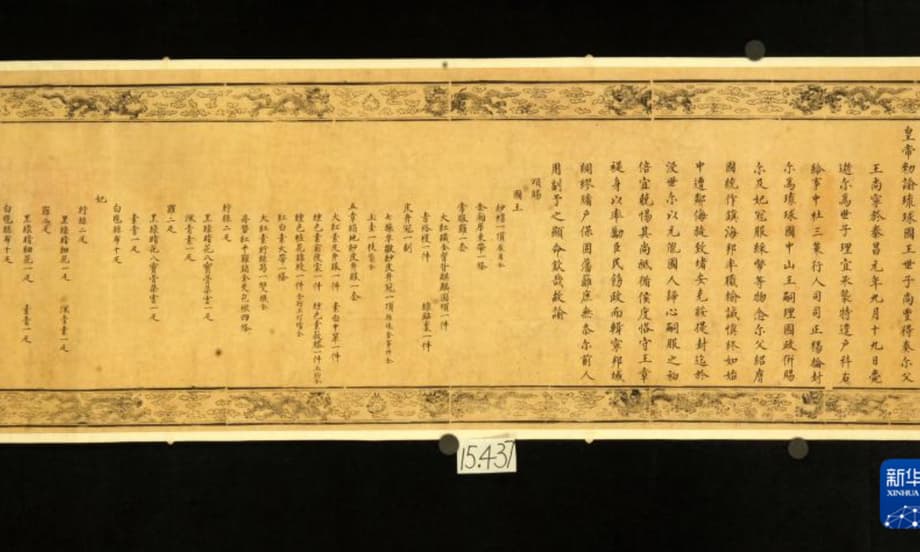

The edict is a carefully crafted state paper. It is written on yellow paper, framed by golden cloud and dragon patterns, and stamped with a square vermilion seal that reads Imperial Seal of Expansive Fortune. The calligraphy is in regular script. The museum displays a replica while keeping the original in its archives, an approach that preserves a fragile artifact and makes its content widely accessible.

Addressed to the King of Ryukyu, the edict recognizes Shang Feng as the new ruler after the death of King Shang Ning (the king known in Japanese sources as Sho Nei). It empowers appointed envoys to bestow the royal investiture on behalf of the Ming court. It praises the late king for loyalty and good service, urges the successor to guard the realm and uphold royal statutes, and lists ceremonial gifts that marked the imperial favor.

The text contains a phrase that the king had suffered harassment from a neighboring state. Museum researchers connect this to the early seventeenth century incursion by forces from Japan that seized the Ryukyu king and looted treasures. The standard Chinese chronicle known as the History of the Ming records the event under the year Wanli 40 (1612). Modern scholarship generally dates the invasion by the Satsuma domain of southern Japan to 1609, a campaign that resulted in the capture of King Sho Nei and a long period of Japanese control behind the scenes.

What the edict granted and how investiture worked

In Ming diplomatic practice, an imperial edict of investiture did several things at once. It recognized the legitimacy of a foreign ruler, fixed the relationship to the dynasty that issued the document, and triggered a cycle of ceremonial exchange. Tribute missions brought local products and formal letters. The court responded with edicts, robes, seals, calendars, and lavish return gifts.

Ryukyu relied on this ritual relationship to secure trade and standing with a powerful neighbor. The 1629 edict is part of a longer thread. Research by museum experts points to 15 investiture missions sent by the Ming to Ryukyu. Each mission was a logistical event that crossed the sea from Fujian, landed at Naha, and staged weeks of court rituals. Envoys installed kings, issued edicts, verified credentials, and in practice kept open a vital channel for commerce.

Ryukyu in the tributary system of East Asia

The tributary system was a set of protocols that structured foreign relations across East Asia for many centuries. The Chinese court framed contact as a hierarchy, but both sides had practical incentives. Smaller polities gained recognition, market access, and security. The court affirmed its central role and regulated exchanges that might otherwise spiral into conflict. Korea and Vietnam were usually ranked as peer neighbors, while Ryukyu, Siam, and others occupied a lower rung, yet all operated within a shared grammar of ceremony and trade.

Ryukyu thrived in this space. Its sailors and merchants connected China, Japan, Southeast Asia, and the islands that curve between Taiwan and Kyushu. Tribute embassies doubled as trading ventures, returning with silk, ceramics, and books, and departing with sulfur, horses, dyed textiles, and pepper. Material culture from Ryukyu shows mixed influences from China and Japan, including lacquerware, textiles, and ritual documents, evidence of a kingdom that acted as a bridge across the maritime world.

Imperial investiture was the anchor of this exchange. The transmission of a seal and edict signaled that a new king had been accepted into the order that Chinese officials recognized. Ritual texts, portraits of foreign envoys, and lists of gifts survive in East Asian archives and museums. They help researchers reconstruct how diplomacy and commerce intertwined and how status was displayed through dress, titles, and carefully staged ceremony.

How often did the Ming and Qing courts invest Ryukyu

By the late Ming, investiture had become routine. The 1629 edict under Emperor Chongzhen is recorded as the last Ryukyu investiture of that dynasty. After the dynastic change in China, Ryukyu sought new documents and seals from the Qing court. According to archival notes preserved by museum staff, early in the Qing period the Ryukyu king returned older edicts and a gilded silver seal to request fresh instruments of rule.

Beijing continued the pattern. The Qing court issued investiture to Ryukyu kings across the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. The final Qing investiture mission reached Naha in 1866, a late echo of a system already under strain. Within a decade, Japan had consolidated domestic rule and moved to formally absorb Ryukyu, a change that brought the tributary era to an end.

Between China and Japan, a complex balancing act

Ryukyu’s position shifted after the Satsuma domain invaded from southern Kyushu in 1609. Satsuma seized the king, forced the kingdom into submission, and imposed tribute and monopolies. Ryukyu retained its royal court and its Chinese investiture, but now answered to two masters. It was expected to continue tribute to China, which Satsuma used to keep access to Chinese trade through a back channel in a time when direct relations were blocked.

The Tokugawa shogunate managed external contacts through what scholars call a four portal system. Nagasaki handled China and the Netherlands. Tsushima mediated with Korea. Satsuma handled Ryukyu. Matsumae handled the Ainu in Ezo. These arrangements knitted Japan into Asian trade while keeping official distance. In this scheme, Ryukyu served both as a subordinate to Satsuma and as a conduit to China.

The 1629 edict itself reflects this delicate position. It praises King Shang Ning for loyalty and prudence and commends him for reporting Japanese interest in Jilong Mountain, a point on the northern coast of Taiwan near Fujian. The Ming court responded by ordering coastal defenses to be strengthened. The document also admonishes the new king to guard the realm, a reminder that Ryukyu sat on contested waters where larger powers tested each other.

What the language and symbols tell us

Every visual element on the edict had meaning. Yellow paper, dragon motifs, and vermilion seals were reserved for the highest commands. The seal text Imperial Seal of Expansive Fortune framed the emperor as a cosmic source of order. The detailed list of gifts did more than reward. Gifts mapped where a king stood in the hierarchy. Silk robes, musical instruments, incense, and seals sent to Ryukyu conveyed status, and they also carried value that could be converted into resources once the mission returned home.

The record that the Ryukyu court returned two old edicts, one decree, and a gilded silver seal early in the Qing period shows how carefully these objects were tracked. A new dynasty in Beijing required fresh instruments that bore its era name. The chain of custody matters for historians today. It allows the piece on display to be linked to specific journeys, envoys, and ceremonies.

The exhibit and the debate it touches

The Lushun Museum chose to re exhibit the edict at a time when maritime history and the legacies of East Asian diplomacy receive close attention. For visitors, the piece offers a tangible connection to a period when a small island kingdom navigated larger powers with ritual, trade, and careful language.

The document is being cited as proof that Ryukyu was a vassal state of China. In the vocabulary of East Asia, vassal meant a tributary partner bound by ritual ties. It did not mean incorporation as a province or direct administration. Ryukyu kept its own court, language, and law, even while it accepted titles and gifts from Beijing and remitted tribute on a set calendar.

Modern politics sometimes reads past documents as claims about sovereignty. Historians caution that the tributary system was a flexible diplomatic order. Ryukyu accepted Chinese investiture because it delivered trade and prestige. Japan allowed tribute to continue because it helped Nagasaki merchants and preserved access to Chinese goods. The language of hierarchy did not always map cleanly onto actual control.

Why the 1629 edict still informs current research

Primary sources like this edict help answer concrete questions. Who held the Ryukyu throne at a given date. Who carried imperial messages. Which routes and ports mattered. They also capture the words officials used in an age of sea change. Phrases about harassment by a neighbor, praise for defending the maritime realm, and commands to safeguard royal statutes add texture to a record that often survives as dry lists.

The edict also illuminates Ryukyu activity around Taiwan and Fujian. The note that King Shang Ning reported Japanese designs on Jilong Mountain underscores how closely the kingdom watched movements near the Chinese coast. Reports from Ryukyu could prompt orders in Beijing to prepare defenses, a reminder that tribute partners also acted as early warning outposts.

Museum research places the document within a chain of investiture papers that moved between Naha and Chinese capitals across dynasties. That chain continued into the nineteenth century, then ended when the Meiji government transformed Ryukyu into Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. The change folded Ryukyu into the modern Japanese state and detached it from the older tributary order.

Short timeline and key figures

1609: Satsuma invades Ryukyu, captures King Sho Nei, and imposes control while leaving the royal court in place. Tribute to China continues with Satsuma supervision.

1612: Chinese chronicle History of the Ming records a Japanese seizure of Ryukyu, the abduction of the king, and the plunder of treasures. The chronicle notes the king was later released, and tribute resumed.

1616: The Ming court receives a report from Ryukyu that Japan considered seizing Jilong Mountain on Taiwan. Orders go out to strengthen coastal defenses.

1629: The Chongzhen emperor issues the edict on display, investing Shang Feng as king after the death of Shang Ning, with praise for the late king and admonitions to the successor.

1640s and after: With the rise of the Qing, Ryukyu returns older seals and edicts to request new ones. The Qing court continues the investiture cycle that the Ming had created. The last Qing investiture mission arrives in 1866.

Highlights

- 1629 Ming edict on show in Dalian recognizes the Ryukyu king and affirms a tributary tie to China

- The edict praises the late King Shang Ning, invests Shang Feng, and lists ceremonial gifts

- Researchers link the phrase harassment by a neighbor to the Japanese seizure of Ryukyu and capture of the king

- The History of the Ming records the event under Wanli 40 (1612) while modern scholarship dates the Satsuma invasion to 1609

- Ryukyu held a dual position, subordinate to Satsuma while maintaining tribute to China to enable trade

- Ming records count 15 investiture missions to Ryukyu, with the 1629 edict as the last for that dynasty

- The Qing court continued investiture, with the final mission in 1866, before Japan annexed Ryukyu in 1879

- The exhibit underscores how the tributary system functioned as ritual diplomacy, trade, and status politics in East Asia