What just happened

Global stocks fell after China escalated its trade confrontation with Washington by banning Chinese companies from doing business with the United States subsidiaries of South Korean shipbuilder Hanwha Ocean. The move landed just as investors were already on edge over a new round of export controls on critical materials, fresh tariff threats, and rising port fees on each side. Sentiment weakened further after United States Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent warned that any attempt by Beijing to slow the global economy would backfire on China.

The selling was broad across regions. United States equity futures fell ahead of the open and the S&P 500 slipped almost 1 percent at the start of trading, then remained lower in early dealings. By the morning snapshot, the S&P 500 was down 0.83 percent and futures were off 0.87 percent. Europe’s Stoxx 600 eased 0.49 percent, while the United Kingdom FTSE 100 was flat. Asia led the losses, with Japan’s Nikkei 225 down 2.58 percent, China’s CSI 300 down 1.2 percent, South Korea’s Kospi down 0.63 percent, and India’s Nifty 50 down 0.42 percent. Bitcoin traded lower near 111.8 thousand dollars.

The selloff marked a sharp reversal from the prior session, when hopes for a meeting between President Donald Trump and China’s President Xi Jinping at the APEC summit nudged risk appetite higher. New sanctions on the United States linked Hanwha units quickly shifted attention back to supply chains, defense works, and maritime trade routes that depend on steady cross border cooperation.

Why the shipping sanctions matter

Hanwha Ocean is a major builder of commercial vessels and naval ships. Its operations reach into the United States through subsidiaries that support ship repair, maintenance, and component supply. By barring Chinese companies from transacting with those entities, Beijing limits access to Chinese parts, services, and financing that often touch global shipbuilding networks, from steel fabricators and engine makers to electronics suppliers and port operators. Even indirect restrictions can ripple through contracts for repairs and refits, delay project timelines, and raise costs for buyers that must find alternative vendors.

Shipping sits at the center of world trade. Any measure that chills port calls, documentation, or payments can slow the movement of goods. The latest step follows a series of new port fees each side introduced on vessels owned or operated by entities tied to the other country. Trade dependent hubs in East Asia and Europe are sensitive to even small disruptions, so a sanction that targets a well known builder with United States ties resonates far beyond one company.

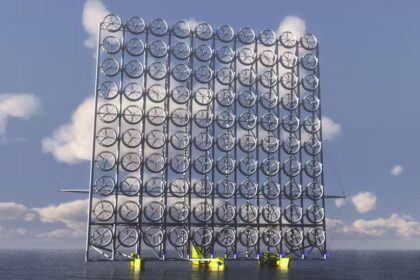

Rare earths and critical minerals are a second front

Beijing’s latest export restrictions on rare earth elements and related magnets add a layer of risk for manufacturers in aerospace, defense, automotive, and clean energy. These are not blanket bans, but they require special licenses and can halt shipments while rules are implemented. Analysts expect the licensing process to cause delays for medium and heavy rare earths, which are the most difficult to substitute. The United States is especially vulnerable here. China has dominated processing of heavy rare earths that go into precision guidance systems, jet actuators, submarine sonar, and advanced radar. Magnets that depend on these materials are also vital for wind turbines and electric vehicles.

Why these materials are hard to replace

China holds substantial shares of global supply and processing for several critical inputs. It accounts for a large share of graphite and antimony production, and the overwhelming majority of gallium and refining capacity for heavy rare earths. Graphite is essential for lithium ion battery anodes, antimony is used in flame retardants and ammunition, and gallium and germanium are used in chips, sensors, and advanced optics. The United States can diversify toward suppliers in Africa, the Americas, and Australia, and the Department of Defense has invested hundreds of millions of dollars to build mine to magnet capability at home. Those projects are moving forward, yet they still represent a fraction of China’s current scale, especially in heavy rare earth separation and magnet making.

Past episodes show how quickly a licensing regime can slow trade. Even when governments intend only to screen exports, paperwork can clog, shipping dates slide, and buyers scramble for alternative sources. Prices can jump if inventory buffers are thin. That is why companies with products that rely on these inputs are watching closely for how fast licenses are processed and what end use rules apply.

Tariff escalation and reciprocal moves

The shipping sanctions land amid a wider tariff and export control confrontation. Washington has threatened triple digit tariffs on Chinese imports on top of a broad schedule of duties. Beijing responded with large additional tariffs on United States goods, tightened controls on rare earth exports, and expanded an unreliable entities list that restricts business with targeted firms. European officials have criticized the tenor of the confrontation and prepared measures to protect their own industries in case diverted trade floods their markets.

This back and forth comes after a United States trade court earlier this year struck down parts of the White House tariff program as exceeding presidential authority, a reminder that legal oversight can influence the timing and scope of new duties. Even when tariffs change on paper, trade can reroute quickly. Economists warn of a global trade diversion, where goods that no longer enter the United States at prior volumes seek other destinations, testing the capacity and political tolerance of third countries.

What officials and analysts are saying

Bessent argued that China, as a top supplier to the world, would bear the greatest cost if it suppresses global growth in a bid to pressure rivals. He also framed the rare earth controls as a signal of weakness rather than strength.