A Serendipitous Crossing in 1983

In the early 1980s, a young New Zealander named Kerry Cox stood at a professional crossroads familiar to many restless souls in their twenties. Having left his stable employment in New Zealand, Cox had relocated to Sydney to study martial arts, driven by a passion for physical discipline and adventure. His journey through Asia would eventually lead him to compete in the World Pugilist Championships in Hong Kong during 1982, but nothing in his training could have prepared him for the challenges he would face in matters of the heart. Separation, silence, and time itself would prove to be formidable opponents.

By January 1983, Cox found himself boarding a ferry bound for Korea, carrying with him only the rumor that air fares from Seoul would prove cheaper than from Japan. The absence of internet or instant communication meant travelers relied on word of mouth and chance encounters for guidance. As he prepared to board, an attractive Japanese woman approached him with limited English but specific advice. She explained that purchasing one box of bananas and a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black Label whiskey would cover most of his travel expenses in Korea, as these Western luxury goods commanded high value in the Asian markets of that era.

Her name was Hitomi. She was traveling with a friend to Korea to purchase clothing and accessories for resale in Japan, a common entrepreneurial practice during Japan’s economic boom years. Cox, who spoke no Japanese, found himself accepting her suggestion that they travel together through an unfamiliar country. She was studying English as a hobby, creating a fragile bridge across their linguistic divide. Neither could have predicted that this practical arrangement would evolve into a lifelong partnership spanning four decades.

From Traveling Companions to Kindred Spirits

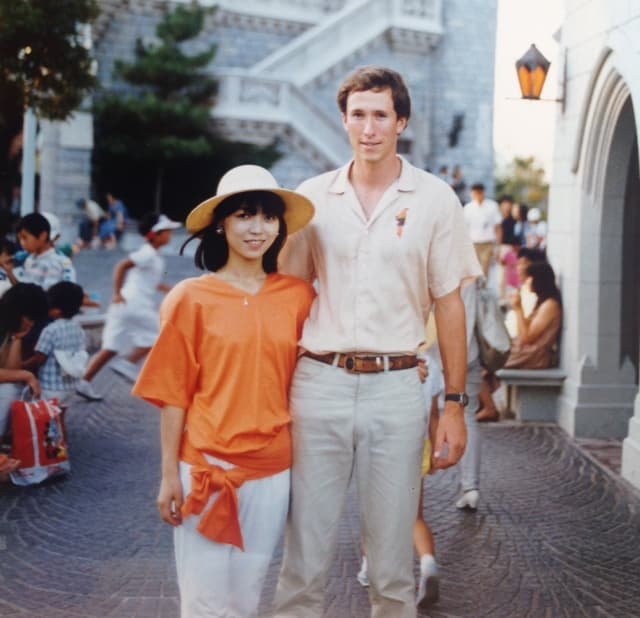

The pair spent a week in Busan, South Korea’s bustling port city, followed by another week in the capital, Seoul. Together they explored local temples and ascended Busan Tower, sharing meals and navigating foreign streets. At this stage, Cox recalls no romantic intentions on either side. The connection appeared purely practical, two solo travelers pooling resources and companionship against the backdrop of an unfamiliar culture. The language barrier remained significant, yet they managed through gesture, patience, and Hitomi’s developing English vocabulary.

However, the economic reality of 1983 quickly intervened. Air fares from Korea proved far more expensive than anticipated, derailing Cox’s travel plans. Hitomi proposed an alternative: return with her to Miyazaki Prefecture in Kyushu, Japan’s southernmost main island, where she lived with her mother in a rural valley surrounded by rice paddies and koi ponds. With no other residences visible for nearly a kilometer in any direction, the setting promised simplicity and respite from urban chaos.

During those weeks in Kyushu, Cox observed Hitomi’s character in ways that transcended language. She traveled extensively throughout the region visiting elderly residents who lived alone and individuals living with disabilities, often bringing small gifts and offering companionship. Her mother initially treated the foreign guest with amusement and hospitality, though underlying tensions would later surface. One local resident spoke of Hitomi with particular reverence.

One local told me they thought she was an angel.

This observation, shared by Cox in his recollections, captured the essence of Hitomi’s gentle nature and her impact on those around her. Her kindness was not performative but habitual, expressed through small gestures of generosity toward society’s most vulnerable members.

The Confession in the Mountain Gorge

The emotional turning point arrived during a visit to Takachiho, a famous mountain gorge in Miyazaki Prefecture renowned for its dramatic cliffs and Shinto spiritual significance. Winter weather had transformed the landscape into a treacherous expanse of snow and ice, forcing the pair to seek shelter overnight at a local tavern rather than risk the return journey. The isolation of the setting, combined with the imminent prospect of Cox’s departure, created an atmosphere where unspoken feelings could no longer remain buried.

That evening, Hitomi asked Cox when he planned to return home to Australia. The question hung in the air between them, heavy with implication. Cox responded with raw honesty, confessing that he was falling in love with her and wished to extend his stay indefinitely. Her reply came as a revelation that would alter both their futures. She looked at him and spoke the words that bridged their separate worlds.

Me too!

The admission shocked Cox, who had not suspected she shared his feelings. Their first kiss followed, which Cox later described as soft and delicate, mirroring Hitomi’s essential nature. The moment represented a transition from friendship to committed partnership, though practical constraints would soon test the strength of their new bond.

Visa expiration forced Cox’s return to Australia. Hitomi accompanied him as far as Narita Airport, where they shared a prolonged farewell that nearly caused him to miss his flight. They established tentative plans for her to visit Australia once arrangements could be made, though neither had yet contemplated marriage. The relationship had emerged so unexpectedly that both needed time to understand its trajectory and depth.

Love Letters Across the Pacific

Distance clarified what proximity had only suggested. As soon as Cox returned to Australia, he understood with certainty that Hitomi was the person he wanted to spend his life with. The geographical separation that might have weakened other bonds instead strengthened his resolve. Communication in 1983 presented significant challenges. International telephone calls remained prohibitively expensive for regular use, forcing the couple to rely on handwritten letters written in English.

Cox simplified his language as much as possible, though he remained uncertain how much Hitomi comprehended of his written expressions. Reading her responses proved equally challenging, requiring patience and interpretation. Yet the meaning transcended vocabulary. As Cox noted, all that truly mattered was finding the words “love you” at the conclusion of each letter. The physical letters, carried across oceans by postal services, became their primary lifeline.

Hitomi attempted to arrange travel to Australia, but her mother stood firmly against the relationship. The parental opposition stemmed from understandable concerns: Cox represented an unknown quantity, a foreigner who might remove her daughter to a distant country with different customs and no guarantee of stability. After a year of separation and limited communication, Cox returned to Japan, hitchhiking south to a business hotel in Kyushu where Hitomi was working late. When she finally knocked on his door and rushed into his arms, a year’s accumulated emotion poured out. In that unromantic setting, Cox proposed marriage, and she accepted.

Silence, Singing, and Separation

The engagement did not resolve the underlying conflict with Hitomi’s mother. She maintained her disapproval, now intensified by the formal commitment. Understanding that Hitomi could not easily leave Japan, Cox returned to Australia to begin the complex process of applying for a visa to reside in Japan permanently. During his absence, a devastating interference occurred unbeknownst to him. Hitomi’s mother began burning the letters Cox sent and hung up the telephone whenever he attempted to call, effectively severing their communication line.

When Cox finally secured his visa and returned to Japan in 1988, five years after their initial meeting, he could not locate Hitomi. The reason proved both glorious and heartbreaking. She had entered a singing competition, won a professional recording contract, and embarked on a national tour as a professional vocalist. Her manager and mother united in blocking Cox’s access, determining that Hitomi had professional obligations that his presence would complicate. The news struck Cox like a physical blow, leaving him stranded in a foreign country without the connection he had crossed oceans to reclaim.

Recognizing he was not welcome in Miyazaki, Cox established himself in Tokyo, enrolling in Japanese language school to improve his communication skills. He supported himself through a patchwork of jobs in pubs, pachinko parlors, and gyms, waiting and hoping for a break in the silence. The pachinko parlors, mechanical gambling establishments ubiquitous in Japanese cities, and gym work provided income while he studied, creating a limbo existence defined by patience and uncertainty.

The Reunion at Shinagawa Station

The break arrived unexpectedly through a mutual friend who telephoned with simple but seismic news: Hitomi was in Tokyo and wanted to meet. They arranged to convene at Shinagawa Station, a major transportation hub in central Tokyo, inside a coffee shop. The years had changed them both. Hitomi had matured into her late twenties, retaining her beauty and gentle manner but carrying the weight of her professional experiences. Cox had transformed from a monolingual foreigner into a Japanese speaker whose linguistic abilities now exceeded Hitomi’s English skills, a reversal that surprised and pleased her.

Their reunion rekindled the relationship with startling speed. Years of forced separation had not diminished their connection; if anything, the obstacles had refined their certainty. They were, as Cox recalls, madly in love. By this point, both had reached thirty years of age, a milestone that carried particular significance in the social context of 1980s Japan. Hitomi’s mother, confronting the reality that her daughter was approaching an age where marriage prospects traditionally diminished, reportedly conceded that no one else would marry a woman of that age. The opposition that had burned letters and blocked phone calls finally yielded to practical acceptance.

A Wedding in Thames

In 1990, seven years after their initial encounter on that Korean ferry, Cox and Hitomi married in a beautiful old church in Thames, New Zealand. The ceremony represented a cultural fusion that captivated Cox’s small hometown. Hitomi wore a traditional white Western wedding dress for the ceremony, then changed into a formal kimono for the reception, creating a visual spectacle that turned heads among the local community. Her mother attended wearing a kimono as well, signaling her full acceptance of the union she had once fought to prevent.

Cox’s parents embraced their new daughter-in-law with enthusiasm that bordered on protective warning. On the wedding day, they pulled their son aside with a directive that mixed humor with serious intent.

If you stuff this up, do not bother coming home!

The remark acknowledged what everyone present could see: Hitomi had won not just Kerry’s heart, but the affection of his entire family. The warning served as both blessing and burden, recognizing the precious nature of the relationship they had fought to preserve.

Forty Years and Final Partings

The couple built their life together in Japan, raising two sons and supporting one another through the inevitable challenges of marriage, parenthood, and aging. Their partnership lasted four decades, a span that included the transformation of Japan from an economic superpower through its periods of stagnation and into the modern era. Throughout these changes, Cox reports he could never take his eyes off Hitomi. In every room, at every age, she remained for him the most beautiful woman present.

Hitomi passed away three and a half years before Cox shared their story with the public. In recounting their history, he expresses gratitude that they found one another again after the years of forced separation and silence. They always maintained that fate had arranged their meeting on that ferry, a chance boarding that altered the trajectory of both lives. Given the choice, they would have married years earlier, avoiding the pain of their prolonged separation. Yet the endurance of their bond through language barriers, parental opposition, professional complications, and geographical distance stands as evidence of a connection that transcended ordinary circumstances.

The Essentials

- Kerry Cox met Hitomi in January 1983 on a ferry traveling from Japan to Korea, where she offered advice about trading goods to fund his travels

- The couple faced significant obstacles including language barriers, Hitomi’s mother’s opposition, and a five-year separation during which she became a professional singer

- Hitomi’s mother burned their love letters and blocked phone calls between 1983 and 1988, while her record label manager also prevented contact

- They reunited in 1988 at Shinagawa Station in Tokyo after years apart, rekindling their relationship despite the silence

- The couple married in 1990 in Thames, New Zealand, seven years after their first meeting, with Hitomi wearing both a white dress and traditional kimono

- They shared forty years of marriage in Japan, raising two sons, until Hitomi’s death three and a half years prior to the story’s publication

- Cox attributes their eventual success to fate, noting they would have married earlier if circumstances had permitted