A discovery that reframes early East Asian society

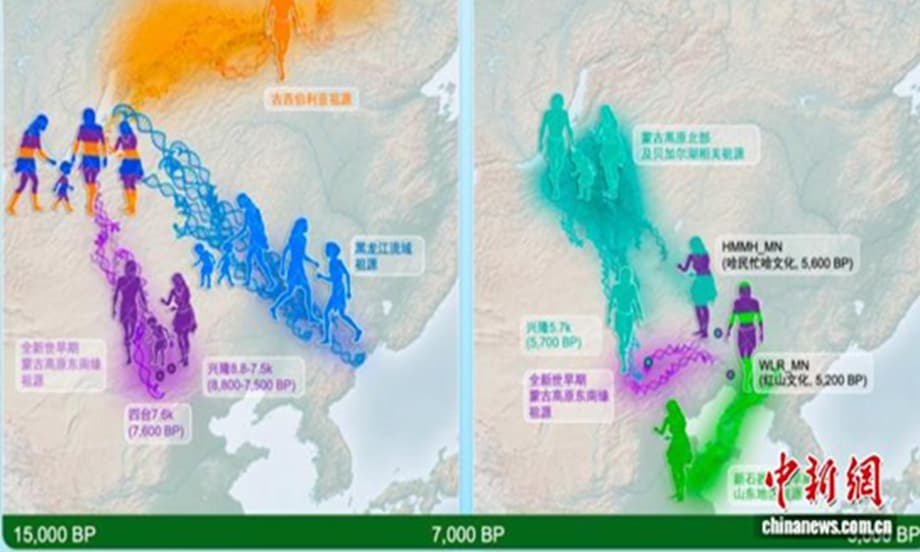

A team of Chinese researchers has identified what appears to be the earliest social structure yet observed in East Asia, and it centers on the household. By sequencing ancient DNA from human remains dated to 8,800 to 5,000 years ago, the group reports that people living on the southeastern edge of the Mongolian Plateau organized their lives around families of parents and children. The finding challenges a long held narrative that early societies in the region moved in a simple line from matrilineal to patrilineal systems as farming spread. Instead, the genetic and archaeological record at these sites points to a family centered model already in place by 8,800 to 7,500 years ago.

- A discovery that reframes early East Asian society

- What the genomes and graves reveal

- Did early societies move in a straight line from matrilineal to patrilineal?

- Marriage rules started early

- An open door beyond kin

- Why this matters today

- How scientists read social life from ancient DNA

- Caveats and what comes next

- Key Points

The work, led by Fu Qiaomei at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), in collaboration with the Hebei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and Xiamen University, focused on two key Neolithic settlements in present day Hebei Province, Xinglong and Sitai. Researchers combined high resolution nuclear genome analysis of 35 individuals with archaeology from houses, tools, and the remains of domesticated millet. The result is a picture of early sedentary communities tied to agriculture, with settlement scale far larger than mobile forager camps. Several joint tombs contained mostly nuclear family units, a pattern that fits households as the main building block of community life rather than a strict matrilineal or patrilineal rule.

Two additional lines of evidence strengthen the case for a flexible, family centered society. First, collective burials at both sites included people who were not biologically related to others in the same tomb. The 13 individuals buried together at Sitai, for example, grouped into three different families along with three individuals unrelated to any of them. Second, genetic screening shows that these communities generally avoided close kin and intra clan marriages. That suggests an early awareness of the risks of inbreeding and the presence of norms that guided how people formed unions. Together these findings point to a cooperative society that could welcome non kin while still valuing the household as a core unit.

What the genomes and graves reveal

Ancient DNA gives scientists a way to reconstruct relationships between individuals who were buried thousands of years ago. In this study, researchers extracted DNA from bones and teeth and sequenced the nuclear genome for each person. Shared segments in the genome identify parent child and sibling ties, while smaller amounts of shared DNA reveal second and third degree relationships. The team compared these results with mitochondrial DNA, which traces maternal lines, and with Y chromosome markers in males, which trace paternal lines. The pattern that emerges at Xinglong and Sitai is clear. Many joint burials pair parents and children. At the same time, neither maternal line nor paternal line dominance appears across the samples, a sign that the core unit was the nuclear family rather than a strictly matrilineal or patrilineal clan.

Archaeology at the sites supports this genetic picture. Houses, storage pits, tools for cultivation, and remains of broomcorn and foxtail millet point to a settled way of life tied to grain production. Joint tombs that cluster around household spaces are consistent with a community organized by families that lived and worked together. The presence of unrelated people in collective burials shows that membership in the community could extend beyond blood ties. Adoption, marriage ties, or social bonds forged through work and ritual are all plausible paths into the group.

Sedentary life and millet farming

Millet was among the first domesticated cereals in North China. As people planted, tended, and stored harvests, they had good reason to settle more permanently. Storage and house based production made the household a natural hub for cooperation and knowledge transfer. In this setting, a family centered organization could stabilize daily life and coordinate labor for planting, harvest, cooking, and childcare. Archaeobotanical traces of millet and tools used to process it tie the economy of these sites to planned cycles of production that fit a settled family unit.

The same genomic data that reveals family ties also indicates who avoided partnering with whom. A lack of close kin unions implies social rules against marrying cousins or other near relatives. That decision reduces genetic risk and can widen networks of exchange. Even in small populations, people in these sites found ways to connect with partners beyond their closest kin, which hints at village level coordination and cultural norms that guided marriage.

Did early societies move in a straight line from matrilineal to patrilineal?

A popular model has long suggested that early farming communities began with maternal lines in control of property and descent and then later shifted to paternal lines as herding and metallurgy spread. The new East Asian evidence does not fit this simple story. Instead of seeing clear maternal or paternal dominance, researchers found households of parents and children nested in larger communities willing to include non kin. That picture points to diversity in how early societies organized power, property, and care, even at the dawn of agriculture in this region.

Findings from other parts of the world reinforce that there was no single path. Work at the famous proto city of Catalhoyuk in central Turkey, for example, has linked intergenerational connections to maternal lines and suggests a female centered structure in the early phases of that settlement. The East Asian record instead shows a mix of family households without strongly marked maternal or paternal control. Side by side, these case studies show that communities at similar times developed distinct social models that matched local ecologies, economies, and traditions.

Marriage rules started early

The team’s analysis of relatedness shows that people living 8,800 to 7,500 years ago in this part of northern China largely avoided unions between close relatives or within the same clan. That pattern points to a conscious social rule rather than random chance. Exogamy, or marrying outside one’s close group, can lower inbreeding risk, bring new skills and knowledge into a household, and build alliances across different families and neighborhoods. Such rules often require shared understanding and sometimes formal enforcement, which means that early communities already had ways to communicate and maintain norms.

These findings contrast with other prehistoric sites where cousin marriage or even closer unions appear in the genetic record, often where population size was pressured or where elite lines kept power tightly controlled. The Hebei sites do not show that structure. Instead, they suggest village level coordination that rewarded wider ties. When combined with the presence of unrelated individuals in collective burials, the picture is of a community that lowered barriers to belonging while guarding against close kin unions.

Marriage norms are not only about partners. They set expectations for residence, inheritance, and childrearing. While the present study does not show a one size rule for post marital residence, it does show that nuclear families were central and that communities could integrate outsiders as full members. That mix of family focus and openness likely helped these settlements grow and endure.

An open door beyond kin

Why would a community include unrelated people in a joint tomb, a space that often carries deep meaning for households and lineage? Several explanations fit the evidence. Unrelated individuals could be spouses who married into the group, adopted children, craft experts, or ritual specialists whose status granted them burial rights with a family. They could also be people taken in during hardship or newcomers welcomed through formal agreements. Whatever the route, inclusion is a social choice, and the communities at Xinglong and Sitai chose to extend belonging beyond blood alone.

The physical setting matters. In many Neolithic contexts, burials sit under floors or near houses, binding the living to the place and to their remembered dead. The same pattern seems present in the Hebei sites, where joint tombs connect to household spaces and daily life. By placing unrelated individuals within these settings, the community sent a clear signal that belonging depended on more than ancestry. That flexibility would have supported cooperation across tasks from farming to childcare and could have buffered the village against shocks.

Why this matters today

Modern East Asian societies wrestle with questions about gender, family, and the balance of work and care. Surveys show that people in the region often hold complex mixes of views. Some prefer traditional roles across both work and family. Others embrace equal roles at home while keeping traditional views of the family, or the reverse. A third group shows weak links between beliefs about work and family. These configurations shape life satisfaction and fertility intentions, which helps explain why shifts in attitudes do not always translate into higher marriage and birth rates.

Policy debates across the region turn on these dynamics. Young adults face high housing costs, long work hours, and workplace cultures that penalize caregiving. Women often shoulder unpaid care while striving for advancement at work. Men are encouraged to be providers even as entry level opportunities shrink. Reforms to childcare, parental leave, and workplace expectations can ease the squeeze, yet progress is uneven. Tension between a family centered welfare model and rising individual aspirations runs through these debates, and it affects how fast policies and norms change.

The prehistoric record from Xinglong and Sitai offers a counterpoint to rigid stories about where family norms come from. Families sat at the center of social life very early in this region, yet those communities also avoided close kin unions and made space for non kin to belong. A society can value households and intergenerational care without locking into a single lineage rule or excluding outsiders. That insight does not solve today’s demographic challenges, but it widens the frame for thinking about communities, caregiving, and inclusion.

How scientists read social life from ancient DNA

Reconstructing family ties from bones is now possible thanks to advances in ancient DNA. Scientists recover fragments of DNA from dense bones and teeth, authenticate them by measuring damage patterns that accumulate after death, and sequence millions of short pieces. They then align these sequences to the human reference genome and check for contamination. By comparing how much DNA two people share across the genome, researchers can identify parents, children, siblings, and more distant relatives. Sex is determined by the presence or absence of Y chromosome reads and by the ratio of reads from the X chromosome to the autosomes.

Genetic data does not stand alone. Archaeologists study the spaces people built and used. House size and layout, hearths and storage pits, tools for grinding grain, and plant remains like millet seeds and silica bodies from plant tissues help reconstruct daily life. Burials capture cultural choices. Who is buried with whom, under what structure, and with which objects, all carry meaning about identity and membership. When both lines of evidence point in the same direction, confidence grows in the social story that emerges.

Every dataset has limits. Burials can reflect a subset of the living community, since many people may be buried elsewhere or in ways that do not preserve. A sample of 35 individuals, while valuable, cannot capture every variation in a region as large as East Asia. Social rules also change over time. Even so, the convergence of genetic kinship, household archaeology, and shared settlement features makes a strong case for a family centered organization at these sites.

Caveats and what comes next

The picture that emerges is regional and time specific. It reflects communities on the southeast edge of the Mongolian Plateau in what is now Hebei Province. To understand how widespread these patterns were, future projects will need genomes and full archaeological context from other parts of North China, the Yellow River basin, the Northeast, and beyond. Data from later periods will clarify what changed as metallurgy, herding, and larger scale political structures appeared.

Several tools can extend the approach. Strontium isotope analysis can identify where a person spent childhood and reveal whether a married couple grew up in the same place or different places. More complete genomes can refine relatedness to second and third degree levels, which helps map extended families. Comparing ancient DNA with environmental records can show whether climate shifts corresponded with social change. The study team published the results as two papers in The Innovation, and they argue that this region served as a cradle for Neolithic society and a hub for cultural exchange that contributed to the formation of a unified multi ethnic China. Testing that larger claim will require many more sites, dates, and datasets across the region.

Key Points

- Ancient DNA from 35 individuals dated to 8,800 to 5,000 years ago reveals family centered households in North China.

- The earliest identified social organization in East Asia, from 8,800 to 7,500 years ago, centered on parents and children rather than a strict maternal or paternal lineage.

- Joint tombs at Xinglong and Sitai mainly contain nuclear families, and neither maternal nor paternal line dominance appears in the genetic record.

- People avoided close kin and intra clan unions, indicating early marriage norms and social regulation.

- Collective burials include unrelated individuals, showing openness to non kin and a cooperative community model.

- Millet cultivation and house based storage reflect early sedentary life that fit a household centered economy.

- The findings challenge a simple shift from matrilineal to patrilineal structures and point to diverse social models across regions.

- The research was published as two papers in The Innovation and positions the region as a key locus in Neolithic development.

- Insights from prehistory enrich current debates about family, gender, and caregiving in modern East Asian societies.