The Final Wish of Ahn Hak-sop: A Life Defined by Division

At 95 years old, Ahn Hak-sop’s life is a living testament to the enduring scars of the Korean War and the ideological chasm that still divides the Korean Peninsula. Captured as a young North Korean soldier in 1953, Ahn spent more than four decades in South Korean prisons for refusing to renounce his communist beliefs. Now frail and confined to a wheelchair, his only wish is to return to North Korea and be buried alongside his fallen comrades. Yet, even this final request has been denied by South Korean authorities, highlighting the unresolved tensions and human costs of a war that technically never ended.

- The Final Wish of Ahn Hak-sop: A Life Defined by Division

- Who Is Ahn Hak-sop?

- The Attempted Return: A Bridge Too Far

- Unconverted POWs: A Vanishing Generation

- The Legal and Humanitarian Dilemma

- Life in the Shadow of the DMZ

- Why Repatriation Is So Difficult

- The Broader Legacy of the Korean War

- Public Sentiment and Political Implications

- In Summary

Who Is Ahn Hak-sop?

Ahn Hak-sop was born in 1930 on Ganghwa Island, during the era of Japanese colonial rule over Korea. His early years were marked by upheaval: his family was torn apart by forced conscription into the Japanese army, and the end of World War II brought not liberation, but a new division. The 1945 proclamation by Gen. Douglas MacArthur placed Korea south of the 38th parallel under American military control, a move that Ahn saw as a betrayal of true independence. This sense of injustice would shape his life’s trajectory.

By the time the Korean War erupted in 1950, Ahn was a middle school student in Kaesong, a city near the new border. He soon joined the North Korean People’s Army, serving in intelligence. In 1953, during a perilous mission behind enemy lines, Ahn was captured by South Korean forces. Out of his ten-man unit, he was the only survivor.

Imprisonment and Unyielding Belief

South Korean law offered captured North Korean soldiers a chance at parole if they renounced communism and pledged allegiance to the South. Ahn refused, enduring 42 years and six months in prison—one of the longest terms for any North Korean POW in the South. He described relentless psychological and physical pressure to abandon his beliefs, including torture and emotional appeals from his family. In his words:

“At first, they tried to convert me through conversation. When that didn’t work, they started torturing me.”

Even after his release in 1995, Ahn felt he had merely moved from a small prison to a larger one, remaining under close surveillance and ostracized by his family for his unrepentant ideology.

The Attempted Return: A Bridge Too Far

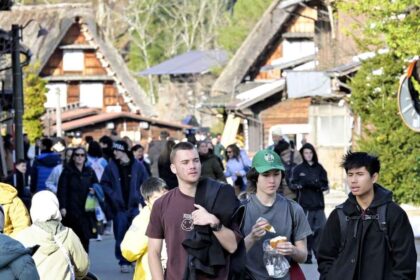

On a recent Wednesday, Ahn made a symbolic journey to the Unification Bridge in Paju, a ceremonial crossing point near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) that separates North and South Korea. Holding a North Korean flag and surrounded by supporters and security personnel, he pleaded to be allowed to cross into the North. South Korean authorities, citing national security laws and the absence of any agreement with Pyongyang, denied his request and escorted him away in an ambulance.

For Ahn, the rejection was devastating. He told reporters:

“I miss the North, it’s unbearable. I want to be buried in the free land.”

His supporters argue that, as a prisoner of war, Ahn has a right to repatriation under international humanitarian law, specifically the Geneva Convention. The South Korean government, however, maintains that unauthorized contact with North Korea is illegal, and the DMZ remains one of the most heavily fortified borders in the world.

Unconverted POWs: A Vanishing Generation

Ahn is not alone in his desire to return north. He is one of six surviving “unconverted” prisoners—North Korean soldiers and spies who spent decades in South Korean prisons for refusing to renounce their beliefs. Most are now in their 80s and 90s, and all have recently petitioned the South Korean government for repatriation. Their numbers have dwindled over the years, and they represent the last living links to a generation defined by ideological conviction and the trauma of war.

In 2000, during a brief thaw in inter-Korean relations, South Korea allowed 63 unconverted prisoners to return to North Korea through the truce village of Panmunjom. Those who returned were welcomed as heroes in the North. Ahn, however, chose to stay, believing his mission was unfinished. He explained his decision:

“If I am to shout, ‘US out,’ I must do it from here, not the North. That’s why I didn’t return. I was determined to die after witnessing the Americans leave this land.”

Since then, no further repatriations have taken place, and North Korea has not responded to recent inquiries about accepting Ahn or others like him.

The Legal and Humanitarian Dilemma

The case of Ahn Hak-sop raises complex legal and humanitarian questions. Under the Geneva Convention, prisoners of war are entitled to repatriation after hostilities end. However, the Korean War concluded with an armistice, not a peace treaty, leaving the two Koreas technically still at war. South Korea’s National Security Law prohibits unauthorized contact with the North, and the DMZ is off-limits to civilians without special permission from both the South Korean military and the United Nations Command.

Human rights groups have expressed sympathy for Ahn and the other unconverted POWs, but few expect the government to make exceptions. The South Korean Unification Ministry has stated it is reviewing the matter from a humanitarian perspective, but any decision would require cooperation from Pyongyang—a prospect complicated by the North’s suspension of all official communications with the South in 2023.

Life in the Shadow of the DMZ

Today, Ahn lives in a modest home in Yonggang-ri, just a mile from the North Korean border. His walls are adorned with North Korean memorabilia, and his doormat is a US flag—a symbol of his enduring opposition to what he calls the “American occupation” of South Korea. Shunned by his family and reliant on government benefits and support from acquaintances, Ahn remains steadfast in his beliefs. He told one interviewer:

“It would be too much of a resentment to be buried in a colony even after death.”

His story is not just about personal conviction, but also about the unresolved pain of a divided nation. For many Koreans, the war is not a distant memory but a living reality, embodied in the stories of separated families, unreturned prisoners, and the ever-present threat of renewed conflict.

Why Repatriation Is So Difficult

The obstacles to Ahn’s return are both political and practical. The DMZ is one of the most militarized borders in the world, lined with barbed wire, landmines, and armed guards. Any civilian crossing requires approval from both Koreas and the United Nations Command. Since North Korea halted all communications with the South in 2023, even humanitarian discussions have stalled.

There are also political sensitivities. Allowing Ahn to return could be portrayed by Pyongyang as a propaganda victory, a symbolic defeat for the South. Conversely, denying his request risks criticism from human rights advocates and international observers who see his case as a humanitarian issue rather than a security threat.

The Broader Legacy of the Korean War

Ahn Hak-sop’s story is a microcosm of the broader legacy of the Korean War. The conflict, which raged from 1950 to 1953, left millions dead or separated from their families. The armistice created a tense ceasefire, but no peace treaty was ever signed. The DMZ remains a stark reminder of the peninsula’s division, and the ideological battle between North and South continues to shape politics, society, and individual lives.

For the handful of surviving unconverted POWs, the war never truly ended. Their lives have been defined by imprisonment, surveillance, and social isolation. Yet, they have also become symbols—both celebrated and controversial—of unwavering conviction in a world where the lines between heroism and fanaticism are often blurred by history and politics.

Public Sentiment and Political Implications

Ahn’s case has stirred debate in South Korea. Some see him as a relic of a bygone era, while others view his plight as a humanitarian tragedy. Civic groups continue to campaign for the repatriation of the remaining unconverted POWs, arguing that their rights under international law have been ignored. The government, wary of security risks and political fallout, remains cautious.

Meanwhile, the broader issue of divided families and unresolved wartime grievances continues to haunt both Koreas. Occasional family reunions, arranged during rare periods of détente, offer fleeting moments of closure for some, but for many, the pain of separation endures to the end of their lives.

In Summary

- Ahn Hak-sop, a 95-year-old former North Korean POW, spent over 42 years in South Korean prisons for refusing to renounce his communist beliefs.

- His final wish is to return to North Korea and be buried alongside his comrades, but South Korean authorities have denied his request due to legal and security concerns.

- Ahn is one of six surviving “unconverted” POWs in South Korea, all of whom have recently petitioned for repatriation.

- The case highlights the unresolved legacy of the Korean War, the ongoing division of the peninsula, and the complex interplay of humanitarian, legal, and political factors.

- Human rights groups and civic organizations continue to advocate for the repatriation of unconverted POWs, but prospects remain uncertain amid strained inter-Korean relations.