A first train, a first ship, and a new supply line

On the Atlantic coast of Guinea, a bulk carrier named Winning Youth waited off the new port of Morebaya with a small but symbolic load, nearly 10,000 metric tons of rich red iron ore. Days earlier, the cargo had left the remote southeastern highlands on the first train to run the TransGuinean railway, crossing hundreds of kilometers of rugged ridges to reach the sea. From there, it began a long journey toward Asia, a voyage that stretches roughly 11,000 nautical miles around the Cape of Good Hope, across the Indian Ocean and the Strait of Malacca, before turning north into the South China Sea. Its likely destination is a steel mill in China, the world’s largest steel producer and iron ore buyer.

- A first train, a first ship, and a new supply line

- How a stalled dream became a 20 billion dollar project

- Ownership, timelines, and scale

- High grade ore and the push to cleaner steel

- Prices and bargaining power shift

- Australia and Brazil face a new rival

- Shipping routes, fleet orders, and tonne miles

- What Simandou means for Guinea

- The Bottom Line

This first shipment marks much more than a test cargo. It signals the opening of Simandou, the largest high grade untapped iron ore deposit on earth. With reserves estimated in the billions of tons and an average iron content that often tops 65 percent, Simandou has the potential to supply up to 120 million tons a year once fully ramped. That would place Guinea among the top tier of iron ore exporters, behind only Australia and Brazil in seaborne trade and comparable with some of the largest national producers.

For China, Simandou addresses a long running vulnerability. The country depends heavily on imported ore from a handful of suppliers, particularly Australian producers in the Pilbara and Brazil’s Vale. By helping finance, build and operate Simandou’s integrated mine, railway and port, China gains a new and diversified supply line for a strategic raw material. The route is far longer than the 3,500 nautical miles from Western Australia to Qingdao, but the ore quality and long term stability of supply are powerful draws for Chinese mills seeking both cost and emissions gains.

Few projects in mining have been as challenging to bring to life. Sidiki Kone, a geologist who worked on early exploration in the late 1990s, recalled the isolation of the Guinea highlands as teams trekked for hours through dense forest to map outcrops and drill targets.

Kone said the forest surrounded his team on every side and he asked himself, “how is this work possible?”

The work proved possible, though painfully slow. With the railway completed enough to run trains and the port able to stage cargoes offshore via barges to large bulk carriers, Simandou has finally moved from ambition to reality.

How a stalled dream became a 20 billion dollar project

Simandou’s story stretches back decades. Geologists recognized its promise in the 1950s, when Guinea was still a French colony. Rio Tinto secured exploration rights in 1997 and confirmed vast resources, but progress stalled. Political upheavals, legal disputes, corruption allegations, and the sheer difficulty of building heavy infrastructure across a mountainous interior delayed any prospect of exports. The project became a byword for unrealized potential.

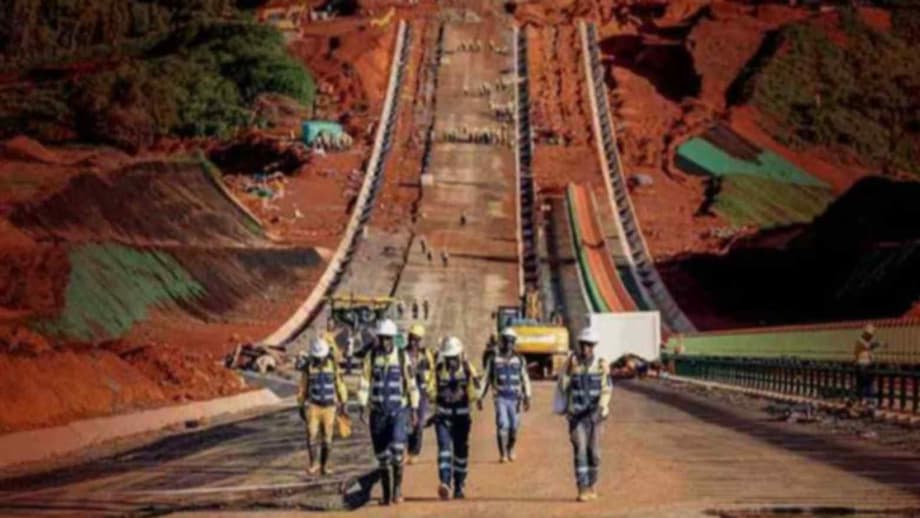

That changed as a coalition formed to push through the required infrastructure. The plan called for a new heavy haul railway of more than 620 kilometers to connect mines in the southeast to a deep water port at Morebaya on the Atlantic. Engineers designed 12 stations, 206 bridges and four tunnels for what is now Guinea’s longest modern railway. The port features offshore transshipment to large capesize and newcastlemax bulk carriers, a practical solution for a coastline with limited draft and complex tides.

On a November day, Guinea’s transitional authorities inaugurated the port and railway, framing the moment as a reset for the country’s development. Officials say the total investment in mine, rail and port exceeds 20 billion dollars. Chinese state champions, international miners and the Guinean government share ownership across the mines and the common infrastructure, reflecting a compromise that unlocked the project after many false starts. The new export line, designed for up to 120 million tons a year, is expected to require a dedicated fleet. Analysts estimate roughly 170 capesize vessels would be needed when Simandou reaches nameplate capacity.

Chinese shipping companies have responded by ordering new bulk carriers and organizing transshipment systems off Guinea’s coast. The maiden lift of Simandou ore is being staged via barges that top up a 200,000 ton bulk carrier offshore, a method that allows large ships to load to full draft without an ultra deep berth. The sailing time to northern China can run about 45 days, which will change trade rhythms and increase tonne miles for the dry bulk market.

Ownership, timelines, and scale

Simandou is split into two major concessions. The northern blocks, known as Blocks 1 and 2, are developed by Winning Consortium Simandou with China Baowu Steel Group as a key partner. The southern blocks, Blocks 3 and 4, are held by a joint venture that includes Rio Tinto Group, Aluminum Corporation of China, and the government of Guinea. The partners agreed to share the railway and port to limit environmental footprints and avoid duplicative corridors across the highlands.

Ramp up will take years. Small volumes have begun to move, but substantial flows are expected to build through 2026. Rio Tinto has targeted a gradual climb toward roughly 60 million tons a year from the southern concession over several years. The combined output of north and south is expected to reach around 120 million tons annually before the end of the decade, subject to construction progress, weather and operational performance. At peak, that volume would equate to roughly 5 percent of global iron ore supply and a high single digit share of global seaborne trade.

The project has faced setbacks. Construction has had to contend with extreme rainfall, difficult ground conditions and safety incidents. Even so, the developer workforce has reached into the tens of thousands, and civil works have accelerated since 2021. The result is one of the largest integrated mine and infrastructure developments undertaken in Africa, with potential benefits that go beyond ore shipments.

High grade ore and the push to cleaner steel

What makes Simandou special is the quality of its ore. Average iron content above 65 percent and low impurities allow steel mills to produce the same tonnage of hot metal with less coke and energy. In blast furnaces, that usually translates into lower emissions and higher productivity. High grade ore also commands a premium price relative to the benchmark 62 percent index, a spread that tends to widen when mills focus on efficiency and emissions.

Industry strategies to cut carbon are starting to shift ore demand toward higher grades. European steelmakers are building or planning direct reduced iron modules paired with electric arc furnaces. Those routes need high grade inputs, including pellets produced from high quality fines and concentrates. Simandou ore could feed that demand, especially if pelletizing capacity grows near the mines or at the port, or if partnerships emerge along the value chain.

Price dynamics will evolve as volumes increase. Market forecasters expect additional supply from Simandou to weigh on the benchmark over time. Some projections place the 62 percent index near the high 80 dollars per ton range in the early 2030s under base case scenarios. In that environment, higher cost and lower grade producers would feel pressure, while mines with strong grades and competitive costs would hold ground. Simandou’s overall costs are higher than those of the lowest cost Australian producers once the long rail haul and ocean freight are included, but the ore’s quality can support a healthy realized price.

Prices and bargaining power shift

Iron ore prices have been choppy this quarter. Futures in Dalian and Singapore have slipped from recent highs as traders weigh robust shipments to China against softer demand signals. Analysts expect hot metal output in China to drift lower in the near term, a sign that mills could reduce ore purchases just as new supply readies to scale.

For Beijing, the strategic attraction of Simandou goes beyond incremental tons. China has spent years trying to reduce its exposure to price swings dictated by a small group of suppliers. It created China Mineral Resources Group to centralize procurement for many state owned mills, and it has pushed for more transactions to be settled in renminbi. There have been tense exchanges with major suppliers over discounts, index pricing and contract currencies. A larger flow from a project in which Chinese companies have significant stakes changes the conversation, even if it does not dictate outcomes in a global market.

John Coyne, a researcher at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, has studied how Chinese market power expresses itself across industrial commodities. He describes how buyer concentration can shift the balance in negotiations when supply is fragmented.

Coyne said, “Where China does not possess a near monopoly, it can control the market through monopsony, a market condition featuring one overbearingly and singularly important customer.”

That dynamic does not eliminate competition among suppliers, and it does not guarantee lower prices in every cycle. It does give Chinese buyers more tools, particularly if they can blend Simandou’s high grade with other ores to optimize costs. As Simandou ramps, Chinese mills will have a new lever in discussions with Australia’s Pilbara miners and Brazil’s Vale, especially in periods when demand softens.

Australia and Brazil face a new rival

In mining circles, Simandou has been nicknamed the Pilbara killer. The label overstates the case. Australian producers operate vast, mature mines tied to very short rail hauls and deep water ports facing Asia. Their overall costs are among the lowest in the industry, often in the 20 to 35 dollars per ton range for the largest operators. By contrast, Simandou must move ore 620 kilometers by rail before it even reaches the coast, then ship three times farther to North Asia than cargo from Western Australia. That raises total delivered costs.

Even so, Simandou is a serious competitor because of grade. In a market where mills value iron units that reduce coke consumption and emissions, materials that average 64 to 67 percent iron can displace portions of blends made with lower grade fines. The most exposed producers are at the higher end of the cost curve, including some domestic Chinese mines and smaller operations in other countries. The arrival of new high grade tons will pressure discounts and premia across the spectrum, tightening margins where costs are already thin.

For Australia and Brazil, the likely outcome is not a collapse in market share, but a reset in bargaining dynamics and price levels. Large Pilbara exporters should remain profitable at lower index prices given their cost advantage. The risk is higher for marginal producers and for projects that require significant new capital to sustain output. The new competition also complicates investment decisions on greenfield projects outside West Africa, since any long term forecast must now account for Simandou at scale.

Shipping routes, fleet orders, and tonne miles

The Guinea to China route is long, and that single fact will reshape dry bulk shipping. If Simandou reaches 120 million tons per year and displaces an equivalent share of shorter haul cargo from Australia, total iron ore tonne miles could rise by around 10 percent. That kind of shift can tighten the capesize market for years by extending round voyages, increasing ballast distances, and adding new seasonal patterns as West African weather and port conditions influence loading windows.

Shipowners are positioning for the change. Chinese builders and operators have booked more large bulk carriers to cover expected lifts from Guinea, while the port’s offshore transshipment design gives charterers flexibility to top up vessels to full draft. Longer voyages also change carbon accounting for shipping, a topic that will matter more as regulators implement emissions reporting and intensity targets for ocean freight. At the same time, high grade ore can reduce blast furnace emissions at steel mills, which complicates any simple tally of Simandou’s net climate effect.

Congestion risk is another consideration. A new export hub feeding long haul trades often creates queuing and weather delays in early years. With a dual track heavy haul railway from the interior and a port designed for high throughput, the system is built for scale. The big test will come as volumes climb past the initial trickle and into tens of millions of tons a year.

What Simandou means for Guinea

The project’s domestic impact could be profound. Guinea’s authorities estimate that Simandou’s expansion could lift national GDP by a large margin over the medium term, with tens of thousands of jobs already created during construction. The state holds a 15 percent non contributory stake in the mining and infrastructure companies, giving the government a direct share of future revenues. Officials also plan to use the railway as a backbone for broader economic activity by moving agricultural products and other freight, and by exploring options for local processing of some ore.

Djiba Diakite, spokesperson for the transitional government and chair of the Simandou 2040 strategic committee, framed the launch in terms that go beyond export volumes.

Diakite said, “Guinea will prove that Africa can avoid the resource curse.”

That ambition will be tested. Simandou runs through one of West Africa’s most biodiverse regions, which demands careful environmental management. Shared infrastructure was a deliberate choice to reduce corridor footprints, but construction and operations still pose risks that must be monitored. Political stability also matters. Guinea is in a transition period, with elections scheduled to move from military to civilian rule. Investors, lenders and local communities will judge the project by how benefits are distributed and by the transparency of its governance.

For neighboring states, the railway and port open new possibilities. Landlocked countries could gain an outlet if capacity allows, while industrial services around the corridor may grow. The coming years will reveal whether the vision of an integrated economic spine from the interior to the coast can take shape alongside the iron ore trains.

The Bottom Line

- Guinea’s Simandou has started exports, with an initial cargo traveling from the interior via a new heavy haul railway to the port of Morebaya.

- At full ramp up, Simandou aims for about 120 million tons per year, roughly 5 percent of global iron ore supply and a high single digit share of seaborne trade.

- The deposit’s high grade, often above 65 percent iron, allows mills to cut coke use and emissions, supporting premium pricing.

- The project is split between a Rio Tinto–Chinalco–Guinea joint venture in the south and Winning Consortium Simandou with China Baowu in the north, sharing a common rail and port.

- Total investment in mine, rail and port exceeds 20 billion dollars, including a 620 kilometer railway and offshore transshipment facilities.

- Chinese buyers gain a diversified supply line, while a centralized procurement body and moves toward renminbi settlement enhance their bargaining power.

- Analysts expect additional supply to pressure benchmark prices over time, squeezing higher cost and lower grade producers most.

- Australia and Brazil remain competitive due to lower costs and shorter routes, though negotiating dynamics shift as Simandou ramps.

- The long Guinea to China haul increases tonne miles, which could tighten capesize fleet utilization and alter trade seasonality.

- Guinea holds a 15 percent state stake and expects job creation and GDP gains, while pledging to avoid the resource curse and manage environmental risks.