A Shift in Global Fighter Jet Development

Japan’s collaborative effort to build a next-generation fighter aircraft is gaining momentum as its European rival encounters significant setbacks. The Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), a joint initiative involving Japan, the United Kingdom, and Italy, may soon establish itself as the leading contender in the race to develop sixth-generation air superiority capabilities. This development follows Germany, France, and Spain indefinitely postponing their Future Combat Air System (FCAS) project, prompting speculation about potential defections to the rival GCAP initiative.

The timing of FCAS delays creates a strategic opening for Japan and its partners. While European nations grapple with political disagreements and industrial disputes over their fighter program, GCAP continues advancing toward its 2035 service entry target. The divergence in progress between these two major defense projects could reshape the global aerospace landscape and influence how nations approach future air combat capabilities.

Inside the FCAS Crisis

The Future Combat Air System was conceived as a cornerstone of European defense autonomy, representing a €100 billion investment by France, Germany, and Spain. Launched officially in 2018, with Spain joining a year later, the project aims to develop a sixth-generation fighter jet alongside unmanned drones and a sophisticated data networking system called a combat cloud. FCAS intended to replace France’s Rafale and Germany’s Eurofighter Typhoon by 2040, maintaining European technological independence from the United States.

Recent developments have cast doubt on the project’s viability. German defence media outlet Hartpunkt reported on December 30 that FCAS had missed an end-of-year deadline set by Berlin for a final decision on whether to proceed. German Chancellor Friedrich Merz expressed frustration with the lack of progress, stating, “We are not making any progress with this project. Things cannot continue as they are.” His comments reflect growing impatience in Berlin as security challenges in Eastern Europe make modern air capabilities increasingly urgent.

The project has already slipped substantially from its original timeline. Initial plans called for a demonstrator aircraft to fly by 2027, with operational capability by 2040. These dates have now been pushed to 2045 and beyond, with no demonstrator construction yet underway. Such delays compromise Europe’s ability to field advanced air capabilities when needed, particularly given Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting heightened security environment on the continent.

The Core of the Conflict

At the heart of FCAS troubles lies a fundamental disagreement over industrial leadership and workshare distribution. The project divides responsibilities among three nations: France’s Dassault Aviation leads development of the Next Generation Fighter jet, while Germany’s Airbus oversees the combat cloud and remote carriers. Spain’s Indra Systems plays a supporting role in sensor development.

France insists on maintaining clear leadership for the aircraft component, with Dassault advocating for a model where the leader exercises complete control over design decisions and subcontractor selection. This approach minimizes intellectual property sharing but conflicts with Germany’s desire to acquire more expertise in fighter aircraft manufacturing. German defense officials dispute French claims that Germany lacks aircraft-building capabilities, while Paris views Berlin’s approach as an attempt to gain access to French technical know-how.

Eric Trappier, CEO of Dassault Aviation, emphasized France’s position, stating, “I don’t mind if the Germans complain. Here, we know what we’re doing. If they want to do it themselves, let them do it themselves.”

Reports indicate Dassault has proposed taking 80% of the workshare for certain components to accelerate development and meet timelines. German lawmaker Christoph Schmid from the Social Democratic Party warned this demand could represent “the last nail in the coffin” for the project if France presses forward with its demands.

Germany’s Strategic Options

As FCAS falters, German officials face difficult decisions about the future of their air combat capabilities. Lieutenant General Holger Neumann, Germany’s recently appointed Air Force chief, has signaled Berlin is prepared to consider alternative paths if FCAS continues experiencing delays. Speaking to Der Spiegel, Neumann emphasized the importance of networking unmanned systems and sensors through a combat cloud, suggesting these elements could proceed even if the manned fighter component faces cancellation.

Germany’s options appear limited by several factors. Unlike France, which has a history of developing combat aircraft independently, Germany lacks recent experience designing fighter jets. The nation’s MTU Aero Engines has not served as a prime contractor on a complete fighter engine for decades, creating substantial technical barriers to a purely national approach. Additionally, Germany’s recent decision to procure F-35 aircraft for NATO nuclear-sharing missions provides some capability but does not address the long-term need for a European sixth-generation platform.

Possible alternatives for Germany include joining the GCAP program, though analysts suggest this would come at the cost of limited influence. Alain De Neve, an aerospace expert at Belgium’s Royal Higher Institute for Defence, noted that while the door to GCAP remains open, its “core” is now established, meaning late entrants would likely receive only secondary roles in systems development rather than prime contractor positions.

Another option involves restarting FCAS with new partners, potentially including Sweden. Such an approach would delay efforts further but might create a more workable partnership structure. Berlin has denied current talks on a new project, but defense analysts suggest Germany has both the resources and motivation to explore this path if FCAS collapses completely.

Spain’s Position

Spain, the third partner in FCAS, faces its own set of challenges if the project dissolves. Madrid previously decided against purchasing American F-35 fighter jets, choosing instead to focus on acquiring Eurofighter Typhoons or future FCAS fighters. Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has signaled solidarity with Germany in the workshare dispute, advocating that previously agreed conditions be maintained.

Like Germany, Spain’s options appear constrained. The nation lacks the industrial base to pursue an independent sixth-generation fighter program. Joining GCAP at this late stage would offer minimal influence or industrial return. Some reports suggest Spain might consider Turkey’s KAAN fighter currently under development, though this option remains speculative and would represent a significant geopolitical shift.

France’s Alternative Paths

France appears better positioned than its European partners to weather an FCAS collapse. The nation has a demonstrated history of withdrawing from multinational fighter projects and developing indigenous alternatives. During the 1960s, France left a NATO fighter project after disagreements over design, ultimately developing the Mirage 2000. In the 1980s, France withdrew from the European Fighter Aircraft Program that produced the Eurofighter Typhoon, choosing instead to create the Rafale, which has become France’s primary military export.

When asked whether France could build a next-generation fighter alone, Dassault CEO Eric Trappier responded simply, “The answer is yes.”

Several factors support France’s ability to pursue an independent path. The Rafale has become an export success, with the United Arab Emirates ordering 80 aircraft in 2021. French arms exports reached €27 billion in 2022, with Rafales accounting for two-thirds of that total. This export success provides funding and potential partnerships that could support a sixth-generation development effort. Additionally, French engine manufacturer Safran’s agreement to co-develop India’s Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft demonstrates Paris’s capacity for international cooperation outside the European framework.

A critical consideration for France involves nuclear deterrence. The FCAS fighter is intended to carry the air-launched component of France’s nuclear deterrent, a role currently performed by Rafale jets. Any future aircraft must maintain this nuclear capability, creating specific design requirements that may complicate cooperation with nations like Germany and Spain, whose Eurofighters lack nuclear delivery functions.

GCAP’s Strategic Advantage

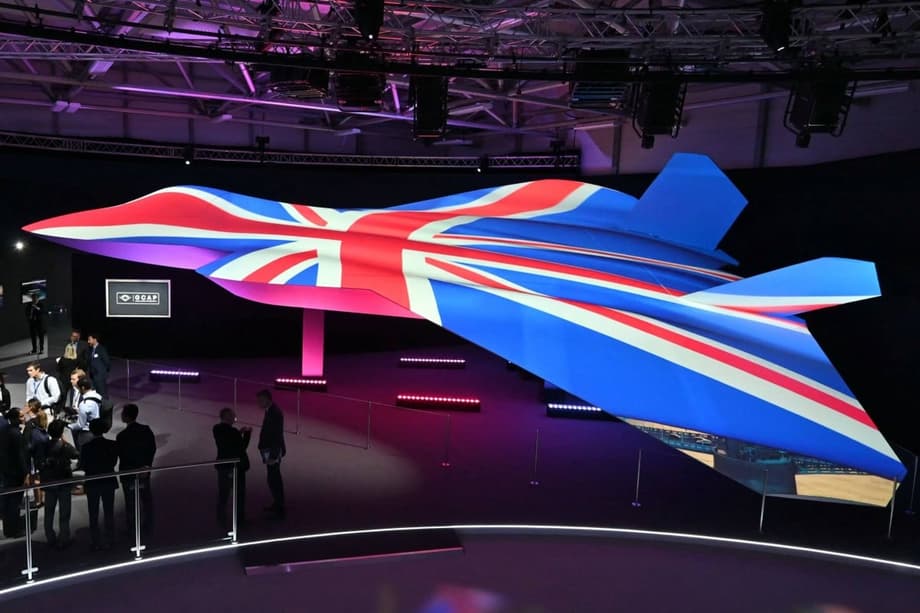

While FCAS struggles, the Global Combat Air Programme continues making steady progress. This collaboration between Japan, the United Kingdom, and Italy aims to develop a sixth-generation fighter to replace Japan’s F-2 and the UK and Italy’s Eurofighter Typhoons by 2035. The project reached a significant milestone in June with the establishment of a joint venture called Edgewing, creating a framework for distributing work among the three nations.

GCAP benefits from several advantages over FCAS. The partnership involves nations with aligned strategic interests and complementary industrial capabilities. Japan contributes significant technological expertise and funding, while the UK and Italy bring established aerospace experience and existing military requirements. The project has already developed a clearer governance structure than FCAS, with defined roles for each partner reducing potential for conflict.

Garren Mulloy, a professor of international relations at Daito Bunka University, provided context on the differing replacement timelines driving these programs. “FCAS has had problems going back some years, partly political and partly because the three nations want to supplement and replace their existing fighters at different times,” he explained. This misalignment created friction absent in GCAP, where partners share more similar operational timelines.

Reports indicate Saudi Arabia has expressed interest in joining GCAP, potentially providing additional funding and export opportunities. Such expansion would further strengthen the program’s industrial base and demonstrate market confidence in the project’s prospects. The possibility of new partners contrasts sharply with FCAS, where current participants struggle to maintain cohesion.

Broader Implications for Global Defense

The divergence in fortunes between GCAP and FCAS carries significant implications for global defense cooperation and European strategic autonomy. A partial or complete failure of FCAS would send a problematic message about Europe’s ability to develop major weapons systems through multinational collaboration. As one analysis noted, it would suggest that “a truly European defence industry cannot emerge as long as incentive structures on industrial and economic interest are national and make compromises too costly.”

The situation highlights the challenges inherent in cooperative defense projects involving sovereign nations with different strategic priorities, industrial capabilities, and political considerations. While such partnerships offer cost-sharing and risk distribution benefits, they also require substantial compromise and shared vision. FCAS demonstrates how differing approaches to technology transfer, intellectual property protection, and export controls can derail even the most ambitious collaborative efforts.

For Japan, GCAP’s progress represents an opportunity to establish itself as a leader in advanced aerospace technology. The nation has historically restricted defense exports but has relaxed these policies to facilitate international cooperation on the fighter project. Success with GCAP could position Japan as a major player in the global arms market and strengthen its security partnerships in the Indo-Pacific region.

The Road Ahead

Germany and France have agreed to delay a decision on FCAS’s future until the end of 2025, providing a window for potential resolution. The outcome of these deliberations will significantly influence European defense capabilities and industrial cooperation for decades to come. Should FCAS survive, its partners must address fundamental governance issues and establish a more equitable workshare arrangement that satisfies all parties.

Should FCAS fail, Europe faces difficult choices about maintaining its fighter aircraft industrial base. Nations may pursue national solutions, alternative partnerships, or procurement of foreign systems. Each option carries economic, strategic, and political consequences that will shape European defense policy for a generation.

Meanwhile, GCAP continues advancing, with a prototype expected by 2027 and service entry planned for 2035. The project’s stability and progress make it an attractive option for nations seeking advanced air capabilities, potentially drawing additional partners away from faltering European initiatives. As one analyst noted, “Given the worsening security challenges in Eastern Europe and globally, Germany in particular did not want to delay the deployment of an aircraft with the potential to dominate the skies.” This urgency may drive more nations toward programs demonstrating tangible progress.

The contrast between GCAP’s steady advancement and FCAS’s delays illustrates a fundamental truth in defense procurement: execution matters as much as ambition. While European officials envisioned FCAS as a symbol of unity and technological independence, practical challenges have proven more formidable than political aspirations. The coming months will determine whether Europe can overcome these obstacles or whether GCAP will emerge as the primary alternative for nations seeking sixth-generation air combat capabilities.

Key Points

- Japan’s GCAP fighter project is gaining advantage as the European FCAS program faces indefinite postponement due to political and industrial disputes.

- FCAS has missed its end-of-year deadline for a decision on continuation, with Germany expressing frustration over lack of progress.

- The core conflict involves Dassault Aviation demanding 80% of workshare and greater control over the aircraft design, while Germany seeks more technology transfer.

- FCAS operational timeline has slipped from 2040 to 2045, with no demonstrator aircraft yet under construction.

- Germany is considering alternatives to FCAS, including potential GCAP participation, though this would offer limited influence in the project.

- France has a history of withdrawing from multinational fighter projects and could potentially develop a sixth-generation aircraft independently.

- GCAP continues progressing toward its 2035 service entry date, with established joint venture structure and potential for additional partners like Saudi Arabia.

- The divergence between GCAP’s progress and FCAS’s delays could reshape global defense cooperation and Europe’s aerospace industry.