Why the yuan is rising in China cross border payments

The yuan has overtaken the dollar as the top currency used in China’s cross border transactions. Official settlement data from the State Administration of Foreign Exchange indicate that the yuan accounted for a majority of payments and receipts through 2023 and into 2024. By May, the local currency’s share reached roughly 53 percent while the dollar fell to about 43 percent. At the same time, yuan settlement in China’s goods trade has climbed to around 28 to 30 percent, compared with about 15 percent in 2021. The change is a milestone for Beijing’s long campaign to expand use of its currency beyond its borders.

- Why the yuan is rising in China cross border payments

- How China got here: from crisis to currency strategy

- What the numbers really say

- Why Beijing wants a trade currency, not a Wall Street currency

- Infrastructure: CIPS, swap lines and the digital yuan

- Who is using the yuan and why

- Barriers that still hold it back

- What to watch next

- The Bottom Line

The shift does not mean the dollar has lost its global lead. Outside China, the yuan’s footprint remains modest. SWIFT data put the yuan at about 4 to 5 percent of international payments and at times in second place behind the dollar for trade finance, ahead of the euro only briefly. The dollar still dominates global trade finance and foreign exchange reserves. IMF figures show the yuan accounts for a little over 2 percent of allocated central bank reserves. The move inside China is meaningful because more commerce with Chinese firms, banks and markets now runs through yuan accounts rather than dollars.

Domestic policy and geopolitics both played roles. Since a 2009 pilot that allowed exporters and importers to settle invoices in yuan, authorities have built a network of clearing banks, swap lines with partner central banks, and a homegrown cross border payments platform. The war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia then accelerated adoption. Russia’s pivot toward the yuan, plus wider interest in currency diversification across parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America, created a larger group of willing users.

How China got here: from crisis to currency strategy

The 2008 to 2009 global financial crisis exposed the risks of relying on a single funding currency for trade and finance. Beijing responded with a long term strategy: promote the yuan as a medium of exchange for trade and investment while keeping the capital account managed. It launched trade settlement pilots, designated offshore yuan clearing banks, and negotiated bilateral swap lines so foreign central banks could borrow yuan to support local banks and companies during periods of stress.

From pilot to a consistent playbook

As the offshore market grew, residents and foreigners gained more ways to hold and use yuan. Stock Connect and Bond Connect created channels between mainland exchanges and Hong Kong, drawing portfolio flows that are always denominated in yuan. Major index providers added Chinese stocks and bonds to global benchmarks, pulling in foreign investment and lifting the yuan’s share in China’s cross border transactions. Panda bonds, which allow foreign issuers to raise funds in yuan inside China, expanded as interest rates in China stayed below United States levels for much of the past two years.

Authorities also built infrastructure. The Cross border Interbank Payment System, or CIPS, processes yuan payments among participating banks. CIPS can operate alongside SWIFT messaging, providing a degree of redundancy if counterparties seek alternatives. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) expanded swap lines to more than 50 central banks, giving partners a backstop source of yuan liquidity that can support trade and financial stability during market disruptions.

What the numbers really say

China’s cross border settlement figures cover all balance of payments categories, not just goods trade. In recent data, portfolio investment transactions account for over 60 percent of cross border yuan flows, goods trade about 20 percent, and direct investment a smaller share. That mix means the surge reflects foreign buying and selling of onshore assets through Connect programs and index inclusion as much as trade settlement. It also means the jump in the yuan’s share of China’s cross border totals does not translate directly into global usage between third countries.

Trade settlement, trade finance and reserves are different scores

In goods and services, companies can invoice and settle in yuan with China if both sides agree. That share has approached 30 percent in 2024. In trade finance, where banks guarantee payment and provide short term funding, the yuan’s share has risen from low single digits to mid single digits, at times taking second place behind the dollar according to SWIFT’s tracking. In central bank reserves, the yuan’s share is around 2 to 2.4 percent based on IMF data, while the dollar is near 60 percent and the euro near 20 percent. These three measures move at different speeds because they serve different functions in the system.

Russia, sanctions and commodity invoicing

Sanctions reshaped China’s network of counterparties. Russian firms and banks now rely heavily on yuan for both trade and finance. Figures from the Moscow Exchange in 2023 show yuan trading volumes surpassing dollars as Russia redirected energy exports to China and imported more Chinese goods. Chinese purchases of Russian oil and pipeline gas are often priced and paid in yuan. Some third countries also settle with Russian entities in yuan to avoid touching dollars or euros during transactions linked to Russian trade.

Why Beijing wants a trade currency, not a Wall Street currency

Chinese policymakers aim to widen use of the yuan in commerce while keeping tight control over domestic finance. Full convertibility would weaken control over interest rates, credit allocation and the exchange rate. The existing framework relies on large state directed banks and capital controls to channel savings to priority sectors and to manage financial cycles. Large, rapid inflows or outflows could destabilize that system and complicate macro policy.

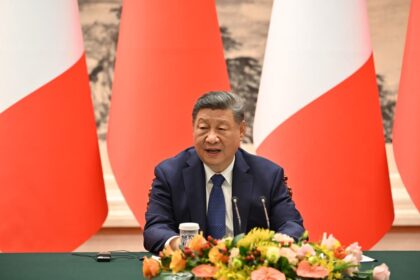

A veteran Chinese policymaker and academic, Huang Qifan, an academic counselor with the China Finance 40 Forum and former mayor of Chongqing, has framed the goal as practical stability rather than rivalry with the dollar. He argues that the point of internationalizing the yuan is to support the real economy and supply chain resilience, not to replace the dollar’s global role.

China’s drive to internationalize its currency is not aimed at replacing the US dollar’s global role, but to maintain the stability of global industry and supply chains.

Infrastructure: CIPS, swap lines and the digital yuan

China’s payments plumbing gives the yuan a broader reach. CIPS now connects hundreds of direct and indirect participants, enabling banks to clear and settle yuan payments with fewer intermediaries. In practice, many cross border yuan payments still rely on SWIFT for messaging, while CIPS handles the settlement leg. Even so, the existence of a parallel architecture provides contingency. For banks and corporates concerned about sanctions risk or messaging outages, redundancy can be valuable.

Swap lines are another key part of the toolkit. The PBOC has signed bilateral arrangements with more than 50 central banks. When activated, these lines allow a partner to obtain yuan to meet demand inside its market, either to settle trade invoices or to provide liquidity to local banks and companies. Swap lines can also signal confidence and reduce transaction costs for partners that do a large share of commerce with China.

Authorities are also testing a central bank digital currency, often called the digital yuan or e CNY. Pilots have covered retail payments at home and some cross border trials with Hong Kong and other jurisdictions. The goal is to make payments faster and cheaper while maintaining regulatory oversight. Experiments with multi central bank platforms have explored how a digital yuan might work in real time FX and trade settlement alongside other currencies.

Who is using the yuan and why

Adoption usually starts with trade exposure. Countries that sell commodities to China or import large quantities of Chinese goods find it simpler to invoice at least part of that activity in yuan. Russia is the clearest example. Some energy exporters in the Middle East and Africa have signaled interest, and several Asian partners use yuan more frequently for intermediate goods trade. In many cases, the draw is not ideology. It is lower friction when the counterparty is a Chinese state firm or when settlement can be matched against yuan receipts from sales into China.

Debt and investment ties also matter. Some African borrowers, including in Kenya, Angola and Ethiopia, have reworked parts of obligations to Chinese lenders to increase yuan use or have issued yuan bonds that pair naturally with yuan trade receipts. In Latin America, Brazil’s central bank raised the yuan’s share of reserve assets to over 5 percent in 2022, a step that aligns with the country’s large trade with China. Across markets, Chinese banks’ external yuan claims have risen quickly, roughly quadrupling over five years to approach 480 billion dollars, which helps fund trade and project finance in the currency.

Capital market channels reinforce the trend. Panda bond issuance has grown as onshore funding costs remain attractive relative to dollar markets. Offshore yuan bonds and loans give multinationals and sovereigns another way to match liabilities with yuan cash flows. As liquidity improves, corporates and banks can hedge more parts of their balance sheets in yuan, which in turn encourages more invoicing and settlement in the currency.

Barriers that still hold it back

Convertibility and controls remain the biggest constraints. The yuan is not freely convertible, and China maintains quotas and approval processes that govern money moving in and out. Offshore yuan liquidity is deeper than a decade ago, yet it is still thin compared with dollar markets. Hedging instruments exist, but depth and tenor are limited in many centers, and clearing capacity can tighten during stress.

Confidence in institutions is another hurdle. Investors cite concerns about data transparency, legal predictability and the handling of financial distress. Episodes of market intervention, abrupt regulatory changes, and a prolonged property slump have made some foreign holders cautious. Weak household demand and ongoing efforts to rein in local government debt have weighed on growth expectations. Those conditions reduce the appeal of holding yuan as a long term store of value for many reserve managers.

Network effects also work against rapid change. The dollar benefits from vast pools of safe, liquid assets and a legal system trusted by global investors. It remains the default in commodity pricing, invoicing and corporate treasury operations. For the yuan to gain ground beyond China related trade, multinational firms would need deeper, more predictable access to yuan funding and hedging, and central banks would need to feel comfortable adding more yuan assets to reserves without sacrificing liquidity or flexibility.

What to watch next

Several signposts will show whether the yuan’s rise extends beyond China facing transactions. The first is the share of China’s goods trade settled in yuan. A sustained move from the high twenties to the mid thirties would indicate deeper adoption by major partners. The second is trade finance. If SWIFT’s tracking shows the yuan consistently holding the number two slot behind the dollar, that would signal broader acceptance by global banks and exporters.

Energy invoicing is another bellwether. Any large, durable shift by major producers to accept yuan for oil or gas sold to China would boost cross border liquidity and demand for yuan assets. Infrastructure capacity is also important. Growth in direct CIPS participation by non Chinese banks, fewer messages routed through SWIFT in yuan payments, and more active use of PBOC swap lines would show greater comfort with the system. Finally, policy settings matter. Steps that widen channels for long term foreign investment, deepen derivatives markets, and offer clearer rules on data and governance would strengthen the yuan’s case as a trade and reserve currency.

The Bottom Line

- The yuan now accounts for a majority of China’s cross border payments and receipts, reaching about 53 percent in mid 2024 based on official settlement data.

- Yuan settlement in China’s goods trade has risen to roughly 28 to 30 percent, up from around 15 percent in 2021.

- Globally, the yuan’s share of SWIFT payments is about 4 to 5 percent, and the dollar remains dominant in trade finance and reserves.

- IMF data show the yuan’s share of allocated central bank reserves is just over 2 percent, far below the dollar and euro.

- Russia’s use of yuan for trade and finance has surged, and yuan trading volumes surpassed dollars on the Moscow Exchange in 2023.

- China’s toolkit includes CIPS for yuan payments, PBOC swap lines with more than 50 central banks, and pilots of a digital yuan.

- Portfolio flows via Stock Connect and Bond Connect drive a large share of cross border yuan transactions.

- Constraints persist, including capital controls, shallow offshore liquidity and concerns about transparency and legal predictability.

- Panda bond issuance and Chinese banks’ external yuan lending are growing, expanding yuan use in trade and project finance.

- Key signals ahead include the yuan share of goods trade, trade finance rankings, energy invoicing practices and the depth of offshore yuan markets.