A Strategic Connection Spanning Centuries

Turkey’s growing engagement in South Asia may seem surprising given the geographic distance between Ankara and New Delhi, but this relationship has deep historical roots that stretch back more than five centuries. Recent events have brought this long-standing connection into sharp focus, with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan pursuing what analysts describe as a neo-Ottoman foreign policy that seeks to expand Turkey’s influence across the Islamic world, particularly in regions once touched by Ottoman power.

In November 2025, Indian investigators suggested that a Turkish handler played a role in coordinating a blast at Delhi’s historic Red Fort. Earlier that year, during military clashes between India and Pakistan in May, Turkey reportedly supplied military equipment and intelligence to Islamabad. These developments point to a renewed Turkish footprint in South Asian geopolitics that has regional powers watching closely.

The historical foundations of this engagement are substantial. Long before the rise of the Ottomans, India maintained trade relations with the Roman and Byzantine empires, whose capital Constantinople later became Istanbul. While those ties faded after Arab conquests transformed the Middle East, connections returned in a new form when Turkic groups took control of Anatolia and founded the Ottoman Empire.

By the early 16th century, the Ottoman Empire had expanded across much of the Middle East and reached the Indian Ocean coastline. It faced powerful rivals—the Shi’a Safavid Empire of Iran and the Portuguese, who were building coastal strongholds from East Africa to India and Southeast Asia to dominate maritime trade.

The Ottoman sultan claimed the title of Caliph or leader of the entire Muslim community after conquering Egypt, seeking to project influence as far afield as Central Africa, Central Asia, and Indonesia.

Religious authority mattered, but survival demanded allies. To counter threats from Persia, Russia and European powers such as Portugal and the Habsburgs, the Ottomans forged ties with states as varied as France, the Uzbek Khanate of Bukhara, Aceh in present-day Indonesia and several Indian kingdoms.

The Mughal Connection

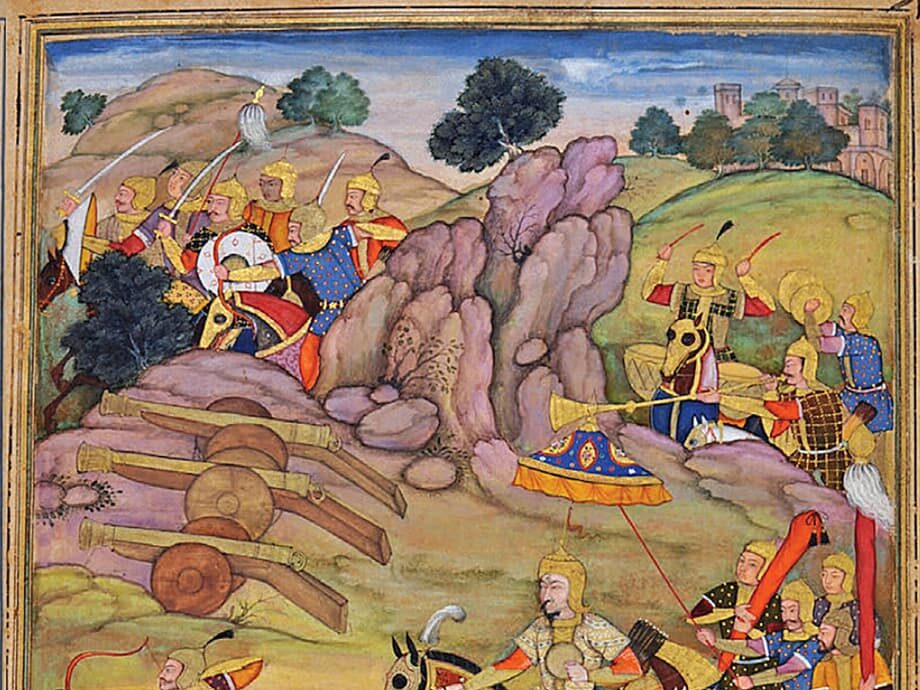

Ottoman influence on South Asia reached its peak through its pivotal role in the rise of the Mughal Empire. At a time when gunpowder weapons were not widely used in the subcontinent, Ottoman artillery transformed Indian warfare. Sultan Selim I dispatched commanders, soldiers, cannons and matchlocks to Babur, the ruler of Kabul.

With this support, Babur went on to establish Mughal rule in India. Relations between the Mughals and Ottomans later moved between cooperation and rivalry, influenced by mutual ambitions and competing claims to religious authority. Many major Indian Muslim states, including the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire, were established by rulers of Turkic origin.

As the Mughal power declined in the 18th century, the Ottomans once again gained importance in South Asia. They remained the only major Muslim empire to avoid European colonisation and continued to claim the caliphate. Smaller Muslim states in India, including Mysore, looked to Istanbul for legitimacy and protection.

Under British rule, the Ottoman sultan held symbolic significance for Indian Muslims. This sentiment culminated in the Khilafat Movement between 1919 and 1922, when Indian Muslims mobilized to defend the Ottoman caliph and oppose British plans to dismantle the empire.

Even after the caliphate was abolished by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the idea refused to disappear entirely. The princely state of Hyderabad explored reviving the caliphate on Indian soil. The Nizam’s sons married Ottoman princesses. Historian Sam Dalrymple notes that in 1931, the Nizam “secured a deed from the last Caliph, nominating their grandchildren as the next Caliphs of Islam.” Hyderabad’s integration into India in 1948 ended those ambitions.

The Three Brothers: Modern Strategic Alignment

In contemporary times, Turkey’s revived focus on South Asia fits into what many describe as a neo-Ottoman foreign policy. President Erdogan views the collapse of both the Ottoman and Mughal empires as historic losses. This worldview has strengthened Turkey’s bond with Pakistan, which sees itself as inheriting the Mughal legacy.

Today, Pakistan, Turkey and Azerbaijan comprise an informal defense grouping known as the “three brothers.” This alliance has become increasingly visible through joint military exercises, defense co-production agreements, and growing intelligence cooperation.

During the May 2025 India-Pakistan clashes—triggered by a terrorist attack in Pahalgam that killed 26 Hindu tourists—Turkey almost immediately took a pro-Pakistani position. Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif expressed gratitude to Turkey for its “unwavering support” for Kashmir.

Reports emerged that Turkey sent military equipment to Pakistan during the crisis. While Turkey denied weapons transfers, it could not deny the presence of its C-130 warplane, which was detected by global air surveillance systems arriving in Pakistan during the tensions.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan during talks with Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif stated the importance of intelligence sharing between the countries to combat terrorism.

The defense dimension of Turkish-Pakistani cooperation has evolved significantly, transforming from traditional arms procurement relationships to sophisticated defense-industrial collaboration. Joint development projects such as the PN Milgem warships and technology transfer agreements in drone warfare capabilities exemplify this transformation.

Military-Industrial Collaboration

Turkey and Pakistan maintain a strategic economic partnership rooted in shared geopolitical interests, strong bilateral ties, and growing trade and investment links. The Pakistan–Turkey Free Trade Agreement entered into force in 2023, regulating trade, investment, and cooperation in the economic sphere. Both countries aim to boost bilateral trade to $5 billion by 2027.

Military cooperation between the two nations is actively developing. Turkish military experts are helping the Pakistani military improve its army. Notable defense projects include:

- MILGEM Corvettes: 4 ships jointly produced under a $1.5 billion deal

- T129 ATAK Helicopters: Pakistan ordered 30 units

- JF-17 Aircraft Cooperation: Turkey has shown interest in aerospace collaboration

Deep cooperation exists between special services and military departments. Turkey’s MIT and Pakistan’s ISI are involved in professional data exchange and cooperation. A significant part of the military cooperation remains non-public and undisclosed.

Turkey’s defense industry has seen remarkable growth over the past decade. Between 2013 and 2023, Turkey increased its defense exports by 106 percent, with the figure exceeding $7 billion in 2023. This success has been driven by game-changing indigenous systems like the Bayraktar drone, which gained prominence during conflicts in Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh and Ukraine.

For India, the prospect of enhanced Pakistani access to Turkish military technology—particularly advanced drone systems—represents a concerning development that could erode its conventional military superiority. The potential transfer of sophisticated Turkish TB2 drone technology to Pakistan would significantly enhance Islamabad’s intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities along the contested Line of Control in Kashmir.

Geopolitical Calculations and Regional Implications

Turkey’s renewed interest in South Asia stems from two broad imperatives. First, Turkish connections with the subcontinent’s large Muslim population and its Muslim states enhance its prestige and role in the Muslim world. In Pakistan, Turkish television, culture and political narratives have gained popularity, with many viewing the country as a model worth following.

The second motive is strategic. Closer security and diplomatic links with Pakistan allow Turkey to display its defense industry, extend its reach into Central and South Asia, counter rival influences from Arab states and keep pressure on Iran, its long-standing competitor.

From Ankara’s perspective, these ties are less about hostility toward India and more about advancing regional ambitions. For Pakistan, however, Turkey appears a dependable partner at a time when Saudi Arabia and Iran both seek warmer ties with New Delhi for their own economic and political reasons.

Turkey’s defense partnership model offers a valuable reference for India as it leverages its geographic position, navigates strategic autonomy, and balances building on indigenous defense manufacturing while still deepening ties with the United States and the West.

The intensification of Turkish-Pakistani relations unfolds against a backdrop of sweeping geopolitical realignments. The United States’ strategic pivot toward India has not escaped the strategic calculus of Ankara and Islamabad, both of which perceive in this alignment a form of strategic encirclement that they seek to offset through enhanced military coordination and economic integration.

The Bangladesh Factor

The geopolitical landscape of South Asia is undergoing broader shifts beyond just Turkey-Pakistan relations. Since the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s government in July 2024, Bangladesh has increasingly viewed India as an adversary while leaning toward Pakistan—the very nation from which India helped liberate it in 1971.

In a major diplomatic breakthrough, Pakistan and Bangladesh signed a visa-free travel agreement for holders of diplomatic and government passports in August 2025. The pact was one of six agreements inked during the visit of Pakistan’s Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Muhammad Ishaq Dar to Dhaka, the first such senior-level trip in 13 years.

Professor Muhammad Yunus, Chief Adviser to Bangladesh’s interim government, has stated that Bangladesh is ‘reaching out to everybody’ in its foreign policy. Yet indications suggest a decisive foreign policy shift, one that signals a break from the India-centric orientation of his predecessor.

Yunus is seeking to reduce reliance on Indian trade in favor of a new strategic alignment with Beijing, and other regional partners like Pakistan and Turkey. This represents an effort to redraw Bangladesh’s regional alliances—a move that may lead to a broader geopolitical shift in South Asia.

Reports claim that Bangladesh is making inquiries about buying Chinese J10 and JF17 fighter jets—the same aircraft that Pakistan’s Air Force deployed in May’s clashes with India. Yunus has also condemned April’s terrorist attacks in Kashmir but India will not be pleased to see another bordering country acquiring advanced military equipment.

The India-Turkey Tension

Relations between India and Turkey remain uneasy. Trade between the two countries is modest, and disagreements persist on multiple fronts. These tensions include Turkey’s support for Pakistan on the Kashmir issue to India’s increasingly warm relations with Greece and Armenia.

The dynamic particularly plays out in the South Caucasus, where Turkey and India have backed opposing factions in the Azerbaijan-Armenia rivalry over Nagorno-Karabakh. Turkey has been a staunch supporter of Azerbaijan, supplying close to $106 million worth of weapons to Baku in 2023, whereas India has aligned closely with Armenia, emerging as its largest defense supplier.

Turkey’s geopolitical conduct and defense partnership model offer valuable lessons for South Asian powers. Turkey has gradually shifted from being a traditional Western ally to a strategically autonomous power, shaped by setbacks in relations with the European Union and the United States.

Turkey’s strategic footing and increased assertiveness have paid dividends, especially in the new world order where Western powers grapple with existential challenges. Turkey has anchored its geopolitical strength in its strategic geography as the eastern gateway into Europe and the western gateway into Asia.

Economic Dimensions and Energy Cooperation

The economic dimension of Turkish-Pakistani cooperation extends well beyond conventional trade relations to encompass strategic sectors with profound geopolitical implications. Energy cooperation represents a cornerstone of this economic partnership.

Turkey’s potential contribution to the extraction and marketing of gas reserves in Pakistani territorial waters offers a pathway for Pakistan to monetize offshore energy resources that have remained largely untapped. For Turkey, participation in Pakistani energy development aligns with its broader ambition to establish itself as a key energy hub connecting Asian resources to European markets.

This energy partnership acquires additional strategic significance when viewed against the backdrop of the stalled Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline project. Pakistan’s pivot toward Turkish energy cooperation suggests a recalibration of its regional economic alignments, potentially at Iran’s expense.

The trilateral relationship between Turkey, Qatar and Pakistan has also gained significance over the past decade. Qatar’s standing as a major Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) producer gives it enormous leverage within energy markets. This financial dynamic remains at the heart of Qatar’s engagement with both Pakistan and Turkey.

As Pakistan’s economy faced severe balance of payment challenges in 2018-2019, Qatar stepped in to support with a package of $3 billion comprised of deposits and direct investment. Similarly, Turkey’s current account deficit has been addressed through Qatari support, with Doha announcing it would invest $15 billion directly into the Turkish economy in 2018.

Future Trajectories and Constraints

Despite its strategic significance, the Turkish-Pakistani partnership faces substantial constraints that will shape its future evolution. Economic vulnerabilities represent perhaps the most significant limitation, with Pakistan’s persistent dependence on International Monetary Fund support constraining its diplomatic flexibility.

Similarly, Turkey’s economic challenges—including currency volatility and inflationary pressures—limit the resources available for ambitious geopolitical projects. These economic realities create leverage points for Western powers seeking to moderate the partnership’s most disruptive potential.

Institutional constraints also shape the partnership’s trajectory. Turkey’s NATO membership imposes certain limitations on its strategic autonomy, particularly regarding defense cooperation with non-NATO partners. Similarly, Pakistan’s complex relationships with China and the United States create competing pressures.

Divergent strategic priorities represent another potential constraint. Turkey’s primary security concerns center on the Eastern Mediterranean, Syria, and the Kurdish question, while Pakistan remains overwhelmingly focused on India and Afghanistan.

Despite these constraints, the Turkish-Pakistani partnership possesses significant potential for future development across multiple domains. Energy cooperation represents perhaps the most promising avenue for deepened engagement. Defense-industrial collaboration constitutes another growth area, with potential expansion from naval platforms to aerospace, missile technology, and electronic warfare systems.

Key Points

- Turkey’s historical interest in South Asia dates back to the Ottoman Empire, which supported the Mughal Empire’s rise through military technology

- Modern Turkey under President Erdogan pursues a “neo-Ottoman” foreign policy seeking influence across the Islamic world

- Pakistan, Turkey and Azerbaijan form the “three brothers” alliance, an informal defense grouping strengthening military cooperation

Turkey supplied military equipment and intelligence to Pakistan during the May 2025 India-Pakistan clashes

Defense collaboration includes joint production of MILGEM corvettes, T129 helicopters, and potential drone technology transfers

Bangladesh is shifting away from India toward closer ties with Pakistan, Turkey and China

Turkey’s motivations include enhancing prestige in the Muslim world and countering Iranian and Arab influence in South Asia

Economic cooperation includes free trade agreements aiming to boost bilateral trade to $5 billion by 2027

The partnership faces constraints including economic vulnerabilities in both countries and Turkey’s NATO obligations

India-Turkey relations remain tense due to disagreements over Kashmir, Armenia, and competing regional interests