The Great Contradiction

In 2025, China achieved a remarkable milestone that would seem to herald the end of the coal era. The country installed 315 gigawatts of new solar capacity and 119 gigawatts of wind power, pushing non-fossil sources past thermal generation for the first time in history. Clean energy sources now account for over 60% of total installed capacity, while coal’s share of actual electricity generation dropped to a nine-year low of 51% in June.

Yet during this same period, China commissioned 78 gigawatts of new coal power capacity, the highest annual total in a decade. More than 50 large coal units, each with generating capacity of 1 gigawatts or more, entered service. To put this in perspective, 1 gigawatt can power several hundred thousand to more than 2 million homes depending on consumption patterns.

The scale of the buildout is staggering. In 2025 alone, China commissioned more coal power capacity than India did over the entire past decade.

This stark contradiction comes from a joint report by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air and Global Energy Monitor. The analysis highlights the central tension facing the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter: even as clean energy crowds coal from the grid, the fossil fuel’s physical infrastructure continues to expand at a pace that threatens to lock in emissions for decades to come.

A Decade High for Construction

The 78 gigawatts added in 2025 represents a sharp break from recent trends. Over the previous decade, China had commissioned fewer than 20 large coal units annually. The 2025 total marks a return to construction levels not seen since 2016, with projections indicating full-year additions could exceed 80 gigawatts.

The first half of 2025 alone saw 21 gigawatts commissioned, the highest first-half total since 2016. Construction started on 83 gigawatts of coal power capacity during the year, with an additional 46 gigawatts restarting work, equivalent to the entire coal power capacity of South Korea. This suggests another wave of completions will arrive in 2026 and 2027.

New and revived project proposals reached 161 gigawatts in 2025, a record high that signals the industry is rushing to secure approvals ahead of potential policy tightening. By year end, 291 gigawatts remained in the development pipeline, either permitted or under construction, representing roughly 23% of China’s existing operational coal fleet.

This expansion is concentrated in coal-rich western provinces. Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Shaanxi led both commissioning and construction starts. More than three-quarters of newly approved projects were financed by coal mining companies or energy groups with mining operations, seeking to secure stable demand for their output through 2030 and beyond.

Energy Security Trumps Climate Goals

The answer to why China continues building lies in a combination of energy security anxieties, structural grid challenges, and economic priorities. In 2021 and 2022, severe droughts in southwest China slashed hydropower output, triggering electricity shortages that forced factory shutdowns and rolling blackouts in some cities. The memory of these disruptions continues to drive policy decisions today.

China’s National Development and Reform Commission, the lead economic planning agency, has stated that coal should play an important foundational and balancing role for years to come. The government views coal as essential backup for wind and solar, which depend on weather conditions and time of day. This philosophy, often summarized as establishing the new before breaking the old, prioritizes stability during the transition.

Additional pressure comes from China’s push to dominate artificial intelligence and advanced manufacturing. Data centers and factories require reliable baseload power that renewables alone cannot yet guarantee, given current storage and transmission limitations. As more of China’s 1.4 billion people enter the middle class, demand for air conditioning and appliances continues to climb, with electricity consumption growing 3.7% in the first half of 2025 alone.

Power shortages in 2021 and 2022 reinforced longstanding concerns about energy security. Some factories temporarily halted production and one city imposed rolling blackouts. The government response was to signal that it wanted more coal plants, leading to a surge in applications and permits for their construction.

The Permitting Pipeline Problem

Much of the 2025 capacity surge traces back to a permitting frenzy that began in 2022. Following the power shortages, provincial governments approved more than 100 gigawatts of coal power annually in 2022 and 2023, averaging two new projects per week. This surge was driven by local concerns about energy security rather than national carbon targets.

Qi Qin, a China analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, explains the persistence of this buildout. “Once permits are issued, projects are difficult to reverse,” she notes. The bureaucratic momentum carries forward independent of changing market conditions. Construction levels in 2024 hit a 10-year high of 94.5 gigawatts, setting the stage for the 2025 commissioning boom.

Although only 25 gigawatts were permitted in the first half of 2025, down from the peak years, new and revived projects reached 75 gigawatts in that period, the highest in a decade. This rush of activity signals possible pressure from the industry to expand coal projects as a last ditch effort before China’s 2030 carbon peaking deadline.

The risk is that political and financial pressure may keep plants operating, leaving less room for other sources of power. Whether China’s coal power expansion ultimately translates into higher emissions will depend on whether coal power’s role is genuinely constrained to backup and supporting rather than baseload generation, according to Qi.

A Global Outlier

While China builds, most of the world moves in the opposite direction. China and India together accounted for 87% of new coal power capacity commissioned globally in the first half of 2025. During the same period, the European Union nearly matched its entire 2023 retirement total, with 2.5 gigawatts closed. Ireland became the fifth EU country to phase out coal power entirely in June 2025.

In Latin America, the shelving of proposals in Honduras and Brazil left the region with zero active coal plant proposals for the first time in recent memory. This followed Honduras entering the Powering Past Coal Alliance in May. The United States, despite policy shifts under the Trump administration, remains on track to retire more coal capacity in 2025 than in 2024, with utilities planning nearly 100 gigawatts of closures by 2035.

This divergence creates a split global energy landscape. Advanced economies are systematically dismantling coal infrastructure while China and India expand it, citing development needs and grid stability. China alone consumes more than half of all coal burned worldwide, making its decisions critical to global emission trajectories.

Just energy transition partnerships are advancing in Vietnam, Indonesia and South Africa, with these countries continuing down dual paths of maintaining coal while planning its eventual phaseout. By contrast, China has not publicly discussed a coal phaseout timeline, leaving the fuel deeply embedded in the power system.

Falling Generation Despite Rising Capacity

Here lies the central puzzle: despite record capacity additions, coal’s role in China’s power mix is actually shrinking. Coal-fired generation declined 2.9% in the first half of 2025, while solar and wind generation grew 20% and 10.6% respectively. Clean energy met all net growth in electricity demand, causing coal’s share of generation to drop even as new plants opened.

The average Chinese coal plant now operates just 47% of the time, down from historical norms around 70%. This falling utilization rate suggests massive overcapacity is already developing. Tim Buckley, director of Sydney-based think tank Climate Energy Finance, notes that the average coal power plant in China for 2025 ran for just 47% of the time, a record low. “If renewable installs can run at anywhere near current rates, and nuclear can pick up to 10 gigawatts a year over the coming decade, we will see a plateau and then slow decline in coal power generation,” he said.

The International Energy Agency projects China’s coal demand will drop to 4,879 million tonnes by 2027 and continue falling to 4,772 million tonnes by 2030. By 2030, renewables are expected to provide 49% of China’s electricity, surpassing coal. This decline would more than offset expected increases in US coal use under current policies.

Meanwhile, China added around 74 gigawatts of new energy storage capacity in 2025, broadly comparable to the coal power commissioned in the same year. This shift toward flexibility-based system resources is steadily reducing coal power’s role in meeting peak demand and balancing the grid.

The Risk of Stranded Assets

With 291 gigawatts in the pipeline and utilization rates plummeting, the country faces a potential wave of stranded assets, power plants that become uneconomical before paying off their construction costs. The 2025 surge reflects a rush by coal industry stakeholders to advance projects ahead of tighter policy constraints, potentially wasting investment and crowding out renewables.

Structural factors protect coal despite its declining economics. Provincial power grids lock in coal supply through medium- to long-term purchase contracts and coal supply agreements that obligate utilities to use the fuel regardless of cost. Capacity payment mechanisms reward installed coal capacity rather than flexibility or actual performance. These arrangements insulate coal plants from market competition while forcing wind and solar developers to face price fluctuations and uncertain demand.

Curtailment of renewable energy is rising as a result. The final quarter of 2024 likely saw a curtailment rate of around 5.5%, rather than the officially reported 3.2%, attributed to structural constraints rather than weather. A large coal power fleet with inflexible dispatching rules risks locking coal into the system and squeezing the operating space for clean energy.

Retirements also lag behind targets. Only 1 gigawatt was retired in the first half of 2025, bringing the total to 16 gigawatts since 2021. To meet the 14th Five-Year Plan goal of 30 gigawatts retired by end of 2025, 13 gigawatts would need to close in the second half, which analysts view as increasingly unlikely.

The 15th Five-Year Plan Crossroads

China’s 2030 climate commitments hang in the balance. The country has pledged to peak carbon emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. To meet these goals, analysts say power sector emissions must not increase between 2025 and 2030, requiring an immediate shift from building new coal to phasing out existing capacity.

The 15th Five-Year Plan, covering 2026 to 2030 and expected for approval in March, represents the critical policy window. Researchers are urging Beijing to set explicit power sector emission peaking targets, halt new coal approvals, and accelerate retirement of aging, inefficient or underutilised units. Without a clear end to net coal power capacity growth, China risks locking in a structural barrier to energy transition.

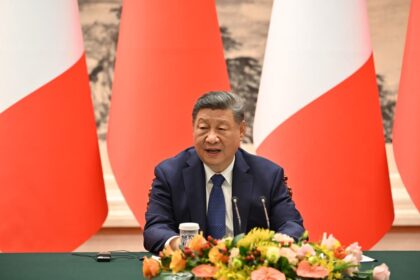

President Xi Jinping is expected to announce China’s Nationally Determined Contributions, a national commitment to greenhouse gas emissions reductions by 2035, before the COP30 climate summit in Brazil. Details are also expected in the Five-Year Plan. The policy direction will be critical to determining the trajectory of China’s coal power sector and with that, its emissions trajectory.

Against this backdrop, the 15th Five-Year Plan represents not merely another planning cycle but a decisive opportunity to reset coal power’s role in line with China’s long-term economic, climate, and energy security objectives. Without reform, the country risks stranding billions in coal investments while missing its climate targets.

Key Points

- China commissioned 78 gigawatts of new coal power capacity in 2025, the highest annual total in a decade, while simultaneously adding 315 gigawatts of solar and 119 gigawatts of wind.

- The expansion traces back to a 2022-2023 permitting surge following power shortages caused by drought and supply constraints, with 161 gigawatts of new and revived proposals reaching a record high in 2025.

- China and India together account for 87% of global coal capacity additions, while the EU, US, and Latin America phase out the fuel.

- Despite new construction, coal’s share of electricity generation fell to 51% in mid-2025, a nine-year low, as renewable growth covered all demand increases and plant utilization dropped to 47%.

- With 291 gigawatts remaining in the development pipeline, China faces risks of stranded assets and overcapacity unless the 15th Five-Year Plan (2026-2030) caps coal expansion.

- The International Energy Agency forecasts China’s coal demand will begin declining by 2027, raising questions about the economic rationale for continued construction.