A city on rations as taps slow to a trickle

An extreme dry spell and relentless heat have pushed Gangneung, a coastal city of about 200,000 people on South Koreas east coast, into a water emergency. President Lee Jae Myung designated the area a national disaster zone in late August after the citys main reservoir sank to critical levels. Officials have throttled water pressure across neighborhoods and shut off 75 percent of household meters to conserve what remains. Public bathrooms and municipally run sports facilities are closed. A third tier football match will be played without spectators, and several events are canceled or postponed as the city redirects every available drop to essential uses.

- A city on rations as taps slow to a trickle

- What the disaster declaration means

- How the crisis unfolded at Obong Reservoir

- Day to day life under restrictions

- Why this drought hit so hard

- Behind the shortages, years of missed fixes

- What authorities are trying now

- How residents and businesses are coping

- What the next weeks could bring

- What to Know

The Obong Reservoir, which supplies roughly 87 percent of Gangneungs tap water, fell below the 15 percent storage threshold widely considered necessary to provide safe drinking water. City figures showed the level slipping to 14.9 percent by Sunday morning after the disaster declaration, then continuing downward. By Sept 7 a national news agency reported storage at about 12.6 percent. Local officials said the city is facing its worst drought in 108 years of weather records, a crisis that follows the hottest summer on record in South Korea. The same heat that scorched the country also dried soils and intensified evaporation, turning a shortage into an acute water crunch.

Rain has been scarce for months. City data show about 38.77 centimeters of rain over the past six months, roughly 45 percent of the average for that period. The Korea Meteorological Administration reports that cumulative rainfall this year was around 40 percent of normal as of the end of August. The result is a municipal system stretched to its limits and an all hands response from central and local authorities.

What the disaster declaration means

The national designation allows the central government to surge aid, personnel, and equipment. After the presidential order took effect, Gangwon Province raised its emergency posture to Level 2 under the Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasures Headquarters system, which triggers a full mobilization. The provincial vice governor leads the headquarters. A support group has been formed that brings together officials from key ministries, Gangwon Province, and the city government to coordinate water deliveries and manage public communication.

Fire agencies and the military are now integral to the water supply. According to provincial officials, 71 fire department tankers have been deployed, including dozens mobilized by the National Fire Agency, with plans for about 2,500 metric tons of water per day through tanker operations. The Korea Forest Service and the Defense Ministry have sent aircraft to ferry water. Two S 64 helicopters that can carry about 8,000 liters each and two Kamov helicopters with roughly 3,000 liter capacity are among those flying. The Coast Guard and Navy are assisting at sea. The 5,000 ton Coast Guard patrol ship Sam Bong delivered about 600 tons of water to Anin port, enough to refill around 50 fire trucks, with more vessels slated to rotate through.

How the crisis unfolded at Obong Reservoir

Obong Reservoir is the citys lifeline. As levels dropped below the 15 percent operating threshold by the end of August, city leaders began taking steps that impact households and farms. The supply of agricultural water was halted to prioritize drinking water. Then came measures inside the city network, including the decision to shut off three quarters of household meters to maintain a minimal level of pressure for remaining users and critical services.

Emergency planning has widened as storage falls. The city forecasts that without meaningful rain, Obong could slip toward single digits in the coming weeks. Officials have warned that if the reservoir falls below 10 percent, time based rationing will begin. The plan calls for cutting water supply overnight from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m., followed by alternate day supply if conditions deteriorate further. The numbers are stark. On Sept 5, Mayor Kim Hong kyu said water from the Hongje purification plant would be cut to 123 sites with large tanks, a group that includes 113 apartment complexes and 10 large hotels. By the citys estimate, tanks at those sites would last two or three days, after which deliveries by truck would begin.

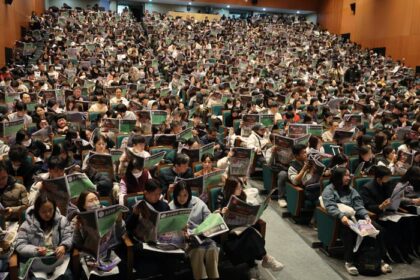

Day to day life under restrictions

Daily routines have changed across Gangneung. Public bathrooms were shut to reduce consumption. All municipally run sports facilities, from swimming pools and tennis courts to a golf club, are closed. Residents have queued at drive through points to pick up bottled water, while city workers distribute supplies to large apartment complexes. Businesses with storage tanks have begun planning for truck deliveries, and hotels are briefing guests on conservation steps as the city prioritizes essential uses.

The mayor has repeatedly urged residents to save every liter. He has warned that voluntary conservation is part of what will keep the system running until weather changes or new supply arrives at scale.

Gangneung Mayor Kim Hong kyu said: “We can survive this drought only if we all conserve and use water sparingly.”

The strain extends beyond residents. The city is a popular seaside destination, and visitor numbers surged this summer despite the dry conditions. Local authorities say the influx puts extra pressure on limited supplies. Tourism officials and city managers are weighing steps to manage water use by visitors in order to support the local economy while protecting the supply that residents need most.

Why this drought hit so hard

Meteorologists describe the event in Gangneung as a flash drought, a rapid drying that unfolds when persistent heat, low humidity, and wind accelerate the loss of moisture from soil and water surfaces. It differs from slow building drought that can take months or years to develop. In a flash drought, demand for water spikes at the same time that supply collapses.

The summer of 2025 intensified that pattern. South Koreas weather agency reported the hottest June to August period since records began in 1973, surpassing the previous mark set in 2024. Heat waves drove up air conditioning demand and evaporation, while rain failed to arrive in the volumes needed to recharge reservoirs. City data show that over the past six months Gangneung received about 38.77 centimeters of rain, just 45.3 percent of the average. KMA records indicate that cumulative rainfall through late August was about 404 millimeters, which is 40 percent of the norm for the same period. Forecasts at the start of September called for less than 5 millimeters on one day and little or no additional rain until at least Sept 10.

Geography plays a role. Gangneung sits on the east coast, separated from central and western parts of the peninsula by the Taebaek Mountains. The barrier can reduce consistent rainfall and create sharp seasonal swings. Much of the regions annual precipitation arrives during typhoons in short, intense bursts that often surge quickly to the sea rather than feeding upstream reservoirs. When heat follows such bursts, little water is left to store. This summer that pattern combined with record heat to push Obong Reservoir toward empty.

Behind the shortages, years of missed fixes

Water scarcity in Gangneung is not new. Since the 1990s the city has cycled through droughts and supply disruptions. In 2002 a typhoon contaminated supplies and cut tap water for days. In 2009 a severe drought left reservoirs depleted. In 2014 levels plunged again before sudden downpours provided temporary relief. As recently as the summer of 2024, storage at Obong fell below 30 percent, which prompted conservation measures. The repeating pattern highlights a key vulnerability: heavy reliance on a single reservoir that lacks the storage capacity of larger multipurpose dams.

Plans to supplement supply have stalled. For years, local authorities and the central government discussed releasing water from the Doam Dam in neighboring Pyeongchang to support Gangneung. Civic and environmental groups opposed the plan, citing water quality and ecological risks. Agencies disagreed over responsibility and acceptable standards. The net result is a system that still depends on Obong and a handful of smaller sources, with few backup options when the main reservoir runs low.

Policy analysts say the current crisis exposes broader gaps in climate readiness across infrastructure. South Korea has faced deadly wildfires, destructive floods, and typhoon damage in recent years. The pattern suggests that systems built for past weather are under stress as extremes grow more frequent. Specialists point to a menu of fixes that could reduce risk. These include connecting more sources to Gangneungs network, strengthening intercity transfer lines, expanding leak detection and pressure management, and scaling up reuse for industrial and outdoor uses so that drinking water is reserved for taps. Several engineers argue that the city should diversify supply by harvesting rainwater from large roofs at schools and gyms, storing it for nonpotable uses such as flushing and irrigation. The goal is to avoid moving from one emergency to the next by building redundancy into the system.

What authorities are trying now

Emergency logistics have ramped up. City, provincial, and national teams are moving water by air, sea, pipeline, and road to slow the decline at Obong and keep treatment plants operating. Helicopters from the Korea Forest Service and the military are flying shuttle runs. The Coast Guard and Navy are staging vessels at local ports to resupply tanker trucks. Fire agencies are running dozens of tankers across the region to deliver water directly to neighborhoods and storage tanks at large facilities.

City officials say they are also drawing from nearby rivers and plants to support treatment. On one day in early September, teams channeled about 26,416 tons of water into the reservoir and purification plants through truck deliveries and temporary pipes connected to the Namdaecheon River. On other days, combined deliveries from helicopters, ships, pipelines, and trucks have approached 30,000 tons, according to government briefings. The city plans to keep this pace until rain returns or storage stabilizes.

Community groups have stepped in. A Catholic medical charity delivered 10 tons of bottled water to parishes for distribution in hard hit neighborhoods. Min Chang ki, director of the Catholic Medical Center, said his organization will keep monitoring needs and continue assistance as conditions change.

Min Chang ki said of the aid shipment: “Though it is a small effort, we hope it helps the citizens of Gangneung and that this severe drought is resolved as soon as possible.”

How residents and businesses are coping

Households are limiting laundry, dishwashing, and bathing, and some have set up small containers to capture rinse water for reuse on plants or cleaning. Apartment residents and hotels with storage tanks are coordinating with the city on rationing schedules and deliveries by truck. Some restaurants have reduced menu items that require large volumes of water and posted signs asking customers to conserve. Farmers have tightened irrigation or paused harvesting of water intensive crops in areas where agricultural supply was suspended.

City government asks residents to report leaks immediately and to avoid nonessential uses such as lawn watering, car washing, or filling private pools. Schools and public offices have posted conservation guidance for students and staff. Faith groups are organizing bottled water donations for elderly residents and those with limited mobility.

What the next weeks could bring

Short term forecasts offered little relief in the first half of September, with only traces of rain expected through Sept 10 and uncertainty after that. If storage at Obong dips below 10 percent, the city will move to timed cuts at night, then alternate day supply if conditions require. The province has warned that without substantial rain in the coming weeks, storage could approach 9.7 percent. Neighboring communities in Gangwon Province, including Samcheok, Jeongseon gun, and Taebaek, have reported emerging shortages, and some have begun preparing emergency measures of their own.

The scale of the current response gives the city some breathing room. Helicopters, ships, and hundreds of vehicles are now part of a daily water bridge. The question for planners is how to build a system that can handle future summers like 2025 without repeated last minute rescues. Engineers and policy makers are debating a mix of new sources, smarter use, and better storage that can stretch supplies when heat and lack of rain align.

What to Know

- President Lee Jae Myung declared Gangneung a national disaster area after its main reservoir fell below the drinking water threshold.

- Obong Reservoir supplies about 87 percent of the citys tap water and dropped from 14.9 percent to around 12.6 percent in early September.

- Officials shut off 75 percent of household meters and cut water to 123 large sites, including 113 apartment complexes and 10 hotels.

- Level 2 emergency status activated a full mobilization across agencies, including 71 fire tankers and helicopters from the Korea Forest Service and the military.

- Coast Guard and Navy vessels are ferrying water to ports, with one 5,000 ton ship delivering about 600 tons to supply dozens of fire trucks.

- On one day the city channeled about 26,400 tons into reservoirs and plants via trucks and temporary pipes, with daily deliveries in some cases near 30,000 tons.

- Public bathrooms and municipal sports facilities are closed. A third tier football match will be held without spectators and other events are postponed.

- Gangneung recorded roughly 38.77 centimeters of rain over six months, about 45 percent of average, during the hottest summer on record in South Korea.

- If storage falls below 10 percent, the city plans to cut supply from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m., then shift to alternate day supply if needed.

- Experts and planners are urging diversified sources, stronger intercity connections, expanded reuse, and rainwater harvesting to reduce reliance on one reservoir.