China’s Ambitious Mega-Dam in Tibet: A New Era for Hydropower and Regional Tensions

China has officially begun construction on what is set to become the world’s largest hydropower dam, located in the remote and ecologically sensitive region of southeastern Tibet. The project, known as the Motuo Hydropower Station or the Yarlung Tsangpo Dam, is not only a feat of engineering but also a source of significant geopolitical and environmental controversy. With a projected cost of 1.2 trillion yuan (about $167 billion), the dam will surpass the scale and capacity of China’s current record-holder, the Three Gorges Dam, and is expected to generate three times as much electricity.

- China’s Ambitious Mega-Dam in Tibet: A New Era for Hydropower and Regional Tensions

- Why Build the World’s Largest Dam Here?

- Engineering Feat or Environmental Gamble?

- Geopolitical Ripples: India, Bangladesh, and the Weaponization of Water

- Diplomatic Deadlock: The Absence of a Water-Sharing Treaty

- The Tibetan Perspective: Displacement, Cultural Loss, and Resistance

- China’s Strategic Calculus: Energy, Security, and Economic Growth

- Global Lessons: The Need for Cooperation and Sustainable Development

- In Summary

The Yarlung Tsangpo river, which becomes the Brahmaputra as it flows into India and the Jamuna in Bangladesh, is a lifeline for millions of people across South Asia. The dam’s construction has therefore raised alarms in India and Bangladesh, who fear for their water security, ecological stability, and even national sovereignty. Meanwhile, China frames the project as a cornerstone of its clean energy ambitions and economic revitalization plans for Tibet.

Why Build the World’s Largest Dam Here?

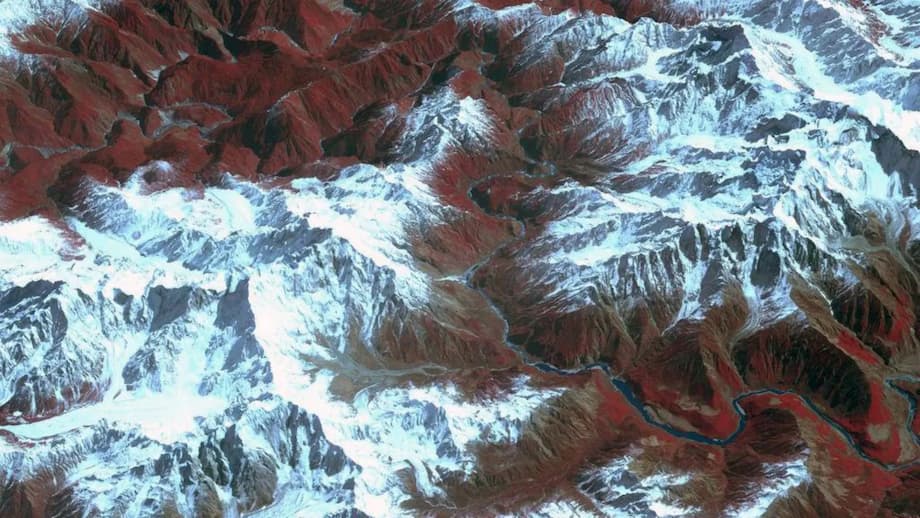

The Yarlung Tsangpo river carves through the world’s deepest and longest canyon as it makes a dramatic U-turn around the Namcha Barwa mountain in Tibet. This “Great Bend” is not only a geographical marvel but also offers a unique opportunity for hydropower generation, thanks to the river’s steep drop of about 2,000 meters over a 50-kilometer stretch. Harnessing this energy, the new dam is expected to have an annual capacity of 300 billion kilowatt-hours, enough to power entire provinces and support China’s growing energy needs.

China’s leadership, including Premier Li Qiang and President Xi Jinping, have championed the project as part of a broader strategy called xidiandongsong (sending western electricity eastwards). The goal is to tap the hydropower potential of Tibet and other western regions to fuel the electricity-hungry cities of eastern China, reduce carbon emissions, and support the country’s pledge to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

To achieve this, engineers plan to build five cascading power stations and drill multiple 20-kilometer-long tunnels through the Namcha Barwa massif, diverting part of the river’s flow to maximize energy production. The electricity generated will be transmitted out of Tibet, with some provision for local consumption.

Engineering Feat or Environmental Gamble?

While the technical ambition of the project is undeniable, the environmental risks are equally staggering. The Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon is a biodiversity hotspot, home to over 4,500 plant species, Asia’s tallest trees, and a remarkable array of large carnivores, including snow leopards, Bengal tigers, and Tibetan brown bears. The region is also a national nature reserve and holds deep spiritual significance for Tibetans, who consider the river sacred.

Environmentalists warn that damming the river could irreversibly alter the ecosystem, flood valleys renowned for their biodiversity, and disrupt the delicate balance of the region’s flora and fauna. The construction site is also in a seismically active zone, raising fears of earthquake-triggered disasters that could threaten both the dam’s integrity and downstream communities.

Past experience with China’s dam-building on other major rivers, such as the Mekong, has shown that upstream dams can cause droughts, reduce fish populations, and disrupt sediment flows vital for agriculture and delta stability. The Yarlung Tsangpo dam could similarly trap vast amounts of sediment, threatening food security in Bangladesh and India, accelerating coastal erosion in the Sundarbans (the world’s largest mangrove forest), and impacting millions who rely on the river for their livelihoods.

Geopolitical Ripples: India, Bangladesh, and the Weaponization of Water

The transboundary nature of the Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra river makes the dam a flashpoint for regional tensions. India and Bangladesh, both downstream countries, have voiced strong concerns about the project’s potential to disrupt water supplies, harm agriculture, and even be used as a strategic tool in times of conflict.

Indian officials, including Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister Pema Khandu, have warned that the dam could pose an “existential threat” to local tribes and livelihoods. Khandu has gone so far as to describe the dam as a potential “water bomb,” capable of unleashing catastrophic floods if China were to suddenly release water during a crisis. India’s Ministry of External Affairs has formally expressed its concerns to Beijing, emphasizing the need for transparency, consultation, and protection of downstream interests.

Bangladesh, where the river is known as the Jamuna, has also requested more information from China and highlighted the risks to its densely populated Brahmaputra basin, where about 70% of the population depends on the river for water, agriculture, and fishing.

Despite these concerns, China maintains that the project has undergone scientific evaluation and will not harm the ecological environment or water rights of downstream countries. Chinese officials argue that the dam will actually help regulate seasonal floods and provide clean energy, while promising to maintain communication with affected neighbors.

Diplomatic Deadlock: The Absence of a Water-Sharing Treaty

One of the most troubling aspects of the Yarlung Tsangpo dam project is the lack of a binding water-sharing agreement between China, India, and Bangladesh. Unlike the Indus River, which is governed by a treaty between India and Pakistan, or the Danube in Europe, which is managed by a convention among 14 nations, the Brahmaputra basin has no formal mechanism for cooperation or conflict resolution.

China has provided hydrological data to India and Bangladesh since the mid-2000s, but experts argue that these arrangements are insufficient to prevent disputes or manage the risks of unilateral dam-building. The absence of a treaty leaves downstream countries vulnerable to decisions made upstream, fueling mistrust and the potential for escalation.

In response, India is reviving its own plans for a massive dam on the Siang river (the Brahmaputra’s name in Arunachal Pradesh), intended as a buffer against sudden water releases from China’s dam. However, experts warn that India’s project could have similar environmental and social impacts, submerging villages and sparking local opposition.

The Tibetan Perspective: Displacement, Cultural Loss, and Resistance

For Tibetans, the dam represents yet another chapter in a long history of resource extraction and marginalization. The Yarlung Tsangpo is not only a river but a sacred entity, believed to embody the goddess Dorje Phagmo. The region’s valleys and mountains are dotted with sites of spiritual and cultural significance, many of which risk being submerged or rendered inaccessible by the dam and its reservoirs.

Thousands of Tibetans have already been forcibly relocated to make way for dams, mining operations, and infrastructure projects. Traditional grazing lands have been flooded or degraded, leading to the loss of livelihoods and accelerating cultural erosion. Protests against dam-building have been met with harsh crackdowns, including arrests and violence, as reported by Tibetan exile groups and international media.

“The cumulative ecological damage threatens not only Tibet’s high-altitude biodiversity but also the health of river systems that sustain communities across South and Southeast Asia,” notes a report from the Tibetan Review. Activists argue that the voices and rights of local communities are being ignored in the rush to develop Tibet’s resources.

China’s Strategic Calculus: Energy, Security, and Economic Growth

From Beijing’s perspective, the Yarlung Tsangpo dam is a strategic asset on multiple fronts. It supports China’s transition to clean energy, helps meet the growing electricity demands of its eastern cities, and provides a stimulus for economic growth in Tibet, one of the country’s poorest regions. The project is also seen as a means of consolidating control over a restive border area and asserting China’s sovereignty in the face of territorial disputes with India.

Vice Premier Zhang Guoqing described the creation of the state-owned China Yajiang Group, which will oversee the dam’s construction, as a “strategic decision for national and energy security.” The dam is expected to begin commercial operations by 2033, with its power primarily transmitted out of Tibet to support China’s broader development goals.

Yet, the project’s scale and location present formidable engineering challenges. Transporting equipment to the remote site, drilling through the Namcha Barwa massif, and managing the river’s powerful rapids all require cutting-edge technology and significant investment. The risks of cost overruns, delays, and unforeseen environmental impacts remain high.

Global Lessons: The Need for Cooperation and Sustainable Development

The Yarlung Tsangpo dam is a microcosm of the broader challenges facing transboundary river management in Asia and beyond. As climate change accelerates glacier melt and alters rainfall patterns, the stakes for water security, food production, and regional stability are rising. More than 1.3 billion people in 10 countries depend on rivers that originate in the Tibetan Plateau, making cooperation essential for sustainable development.

Experts and environmentalists have called for a trilateral water-sharing agreement between China, India, and Bangladesh, modeled on successful examples like the Danube Convention in Europe. Such an agreement could help ensure equitable access to water, protect ecosystems, and prevent conflicts. However, deep-seated mistrust, competing national interests, and the absence of a shared legal framework make progress difficult.

As China pushes ahead with its mega-dam, the world will be watching to see whether the project becomes a symbol of technological progress and regional cooperation—or a flashpoint for environmental degradation and geopolitical strife.

In Summary

- China has begun building the world’s largest hydropower dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo river in Tibet, with a projected cost of $167 billion.

- The dam will generate three times the electricity of the Three Gorges Dam and is central to China’s clean energy and economic goals.

- India and Bangladesh, both downstream, fear for their water security, ecological stability, and livelihoods, warning of potential “water weaponization.”

- Environmentalists highlight risks to biodiversity, sediment flows, and the dangers of building in a seismically active region.

- Tibetans face displacement, cultural loss, and ecological damage, with little say in the project’s development.

- There is no binding water-sharing treaty between China, India, and Bangladesh, increasing the risk of conflict.

- Calls for regional cooperation and sustainable river management are growing, but deep mistrust remains.