A ruling decades in the making

A South Korean court has erased a conviction that shadowed a woman for most of her life, declaring that Choi Mal ja acted in lawful self defense when, as a teenager in 1964, she bit off part of a man’s tongue while escaping an assault. The Busan District Court acquitted Choi, now 79, and found there was no proof the man suffered a permanent disability from the injury. The decision closed a rare retrial and corrected a judgment entered six decades ago that had branded a victim as a criminal.

- A ruling decades in the making

- How a teenager became a defendant

- The long path to a retrial

- What the court decided

- Why the apology matters

- How social change prepared the ground

- Can a case be tried again after a conviction

- The human cost of six decades

- Damages claim and what could change next

- What the decision says about modern South Korea

- The Bottom Line

The original case became a symbol of how the justice system once treated survivors of sexual violence. Court records show that when the attack occurred, the man forced his tongue into Choi’s mouth and pinned her to the ground. She fought free only by biting off about 1.5 centimeters of his tongue. Yet she received a suspended 10 month sentence for causing grievous bodily harm, while the man was given a lighter suspended term for trespass and intimidation after prosecutors dropped the attempted rape count against him.

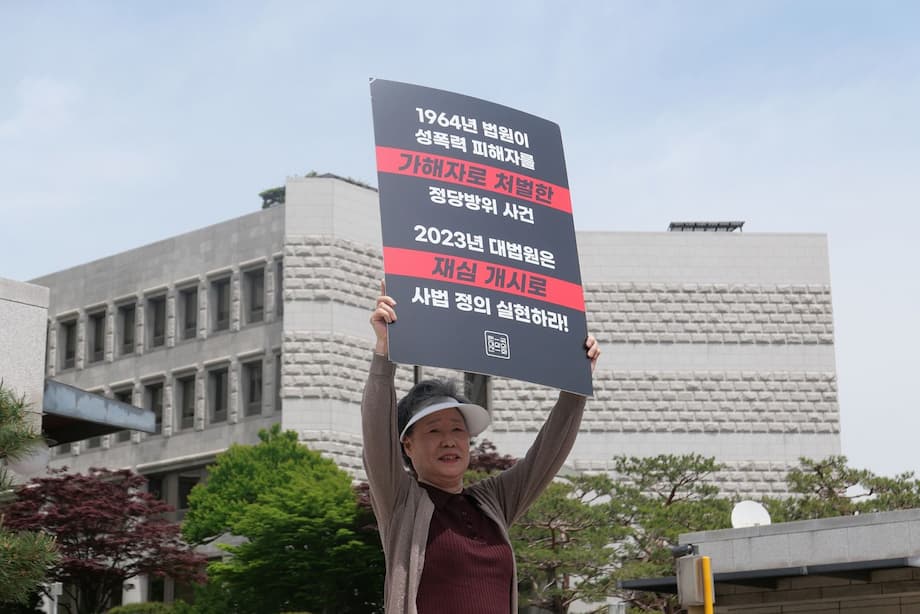

Outside the court after her acquittal, Choi raised a fist as supporters cheered and handed her bouquets. Activists waved a placard that read, Choi Mal ja did it. The celebration followed years of public pressure, legal advocacy, and a rare apology from prosecutors who acknowledged that the state had treated a victim as an offender.

How a teenager became a defendant

The assault took place in the southern town of Gimhae, near Busan, according to records cited by multiple outlets. Choi, then in her late teens, was overpowered and suffocated as the attacker pressed his tongue into her mouth and at one point blocked her nose to stop her from breathing. She broke free by biting down, then reported the crime. The man sued her for bodily harm. She counter filed for attempted rape, trespass, and intimidation.

In the South Korea of the mid 1960s, social norms tilted heavily against women. The country focused on rebuilding from war and colonial occupation, and many victims of violence had little protection or voice. Domestic violence was so routine that there was not even a widely used word for it in public conversation. Trials often asked survivors to prove their chastity, rather than addressing the assault itself.

Choi’s first trial captured those realities. She has said she was handcuffed and compelled to undergo a test to prove virginity, and that the result was made public. Prosecutors and judges asked whether she would marry the man to bring the case to a close, suggesting that becoming his wife might compensate for his injury. The court then ruled that her bite exceeded the reasonable bounds of self defense and convicted her of grievous bodily harm.

Legal experts later used her file in teaching, citing it in textbooks as an example of how courts misread acts of self preservation during sexual violence. Wang Mi yang, who leads the Korea Women Lawyers Association, has argued that the first ruling reflected social prejudice that punished the wrong person.

Wang Mi yang, president of the Korea Women Lawyers Association, said the early judgment revealed deep bias and warped views about victims of sexual violence, which turned a survivor’s effort to escape into a crime.

The long path to a retrial

Choi’s decision to fight back in court came well after she had built a life under the weight of a record. Waves of women’s rights activism, from the comfort women campaigns of the 1990s to the surge of #MeToo in South Korea in 2018, encouraged her to try to clear her name. She filed a petition for a retrial in 2020, which lower courts initially rejected.

She and her supporters persisted. After years of campaigning and public rallies, South Korea’s Supreme Court agreed in 2024 that a retrial could proceed in Busan. When the new proceedings opened, prosecutors did something that almost never happens. They apologized in open court and asked that her conviction be quashed.

Speaking to reporters during the retrial process, Choi described what it meant to carry a conviction that she believed was unjust.

Choi said: “For 61 years, the state made me live as a criminal.” She added that she hoped future generations could live happy lives free from sexual violence.

The lead local prosecutor also addressed her directly by name rather than as a defendant, a break from past practice, and took responsibility for the harm caused by the first case.

Busan Chief Prosecutor Jeong Myeong won said: “We sincerely apologise. We have caused Choi Mal ja, a victim of a sex crime who should have been protected as one, indescribable pain and agony.”

As the final ruling arrived in September, Choi left the courthouse and told supporters, We won. For many, that meant more than a personal victory. It read as an acknowledgment that survival can require force and that the law should recognize that truth.

What the court decided

The Busan District Court concluded that Choi’s actions met the standard for lawful self defense. Judges found that she used the force needed to escape an unlawful assault that threatened her bodily integrity and sexual self determination. The court also cited medical records and testimony to say there was not enough evidence that the attacker suffered a lasting disability from the bite. That undercut a central element of the original charge of grievous bodily harm.

The ruling reverses the thinking that guided the first verdict, which had held that biting the assailant’s tongue exceeded the reasonable bounds of self defense. In the retrial, the court read the facts from the vantage point of the victim being pinned, suffocated, and trying to survive. The law asks whether there was an immediate unjust attack and whether the response was necessary to repel it. The judges said yes on both counts.

Self defense under Korean criminal law

South Korea’s Criminal Act recognizes self defense when a person confronts an unlawful and immediate attack and uses means that are necessary and proportional to repel it. Courts examine context. They look at the nature of the threat, whether escape was possible, and what force was required to end the danger. Early in the case, the justice system framed Choi’s bite as an overreaction. The retrial returned to first principles. It saw a teenager with her airway obstructed and her body restrained, and it treated her bite as a reasonable act to break free.

Why the apology matters

Public apologies from prosecutors are rare, and this one signaled a wider shift. The statement in court acknowledged that authorities had failed to protect a crime victim and, by pressing the wrong charge, prolonged her suffering for decades. The change in tone, including addressing Choi by name and asking for acquittal, reflects a prosecution service that has absorbed years of public criticism over its handling of sexual violence cases.

Choi herself struggled to believe that the system had finally recognized her account. After one hearing earlier in the retrial, she told reporters that seeing prosecutors admit error gave her faith that justice is alive in the country.

“I still cannot believe it,” Choi said after the hearing. “But if the prosecution is admitting its mistake even now, then I believe justice is alive in this country.”

Her words resonated beyond Busan. Advocacy groups that had stood with her across years of petitions and protests saw the acquittal as a message to survivors who fear that reporting an assault will turn them into the accused.

How social change prepared the ground

Choi’s retrial unfolded in a country that has undergone a deep rethinking of gender based violence. In the 1990s, grassroots campaigns sought justice for the women forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military during World War II. That movement helped place the rights and dignity of survivors at the center of public debate.

Then, in 2018, the #MeToo wave reached South Korea and took root. High profile accusations led to court cases against powerful men, and street protests pressed for better policing and stronger penalties for sexual crimes. Lawmakers increased punishments for hidden camera violations and lawmakers and courts reconsidered norms that had long discouraged reporting. The Constitutional Court also struck down the criminal ban on abortion, a decision that reflected the same broader push to respect bodily autonomy.

All of this created space for cases like Choi’s to be re examined. Her file, once a cautionary tale about supposed limits on self defense, now appears in legal teaching as evidence of how courts can get it wrong and how they can correct a mistake when social understanding changes and the law is read through the lived experience of a victim.

Can a case be tried again after a conviction

Many readers wonder how a court could revisit a case that seemed settled for decades. In criminal law around the world, the rule often called double jeopardy protects people from being tried twice for the same offense after an acquittal or a final conviction. Legal systems, however, also create safety valves to fix miscarriages of justice. South Korea allows a defendant to seek a retrial if new evidence emerges, if procedural errors undermined the original case, or if legal understanding evolves in a way that could change the result. The Supreme Court can authorize that retrial, which is what happened in Choi’s case.

That means Choi was not prosecuted again for the same offense at the request of the state. She, as the convicted party, asked the courts to reopen the record and review the charge with a fuller understanding of the facts and the law. The Busan District Court then held a new hearing and issued an acquittal, which restores her legal status and erases the conviction.

The human cost of six decades

Clearing a record cannot give back years lost, and Choi has spoken about the burden she carried. She has described a life lived under a cloud of resentment and unfairness. In a letter to the Supreme Court, she wrote that the country must make amends for violating her human rights. That pain was not only emotional. A criminal record can restrict jobs, social standing, and trust, especially in a generation for whom reputation shaped life’s milestones.

Choi also remembers the indignities of the first proceedings. The handcuffs. The invasive virginity test and the fact that officials made its result public. The suggestion that marriage to the man might somehow settle the matter. Her supporters say those details explain why many survivors stayed silent in that era and why some still hesitate to report violence today.

Her case shows that a single ruling can mold attitudes for years. It discouraged victims who feared being doubted or blamed, and it taught generations of law students about the dangers of reading self defense narrowly. The new judgment reverses that lesson. It tells survivors that the law can see them and can accept the force needed to survive.

Damages claim and what could change next

With the criminal case resolved, Choi’s lawyers have said they plan to seek compensation from the state. South Korean law allows people who were wrongfully convicted to be compensated for time in custody and for the harm caused by a faulty judgment. Courts can also order restoration of honor measures that make clear a person was cleared. The details of any damages claim will depend on the time she was detained, the scale of harm the court recognizes, and the evidence of lasting effects on her life.

A successful claim would not only provide redress. It could also nudge institutions to update training for police, prosecutors, and judges on how assaults occur and how victims respond in the moment. Law schools already teach the early ruling as a cautionary example. Now they can pair it with the retrial decision, which aligns the doctrine of self defense with the reality of surviving an attack.

What the decision says about modern South Korea

Public reaction to Choi’s acquittal reflects a country that is actively reassessing its past and adjusting its legal lens. The apology from prosecutors, the clear statement on lawful self defense, and the visibility of survivor advocacy together suggest that institutions do not stand still. Courts can reinterpret the same facts through a different frame when social knowledge advances and when the lived experience of victims is given proper weight.

That does not mean every case will be reopened or that every claim of self defense will succeed. It does mean courts are more likely to consider the split second choices people make under threat, and to evaluate force not in the abstract but in the context of survival. For survivors who have long feared they will be blamed for how they fought back, that shift matters.

The Bottom Line

- Busan District Court acquitted 79 year old Choi Mal ja, ruling she acted in lawful self defense in a 1964 assault.

- The court found insufficient evidence that the attacker suffered a permanent disability from the bite and rejected the original view that she exceeded reasonable bounds.

- Prosecutors issued a rare public apology and asked the court to clear her record during the retrial.

- Choi petitioned for a retrial in 2020, faced initial rejections, and won Supreme Court approval in 2024.

- The case became a touchstone in legal education for how courts can misread self defense in sexual violence cases.

- Women’s rights activism, including #MeToo, helped create momentum for the retrial and broader reform.

- Choi’s lawyers plan to seek state compensation for the harm caused by the wrongful conviction.

- The ruling is seen as a marker of changing attitudes toward survivors and a more accurate understanding of self defense in law.