A manufacturing shift gathers pace

North of Hanoi, the landscape of Bac Ninh shows how global manufacturing is being rewired. Warehouses and assembly halls have replaced rice fields as Chinese manufacturers, squeezed by tariffs and risk, establish plants in Vietnam to keep access to key markets. This relocation began during the first phase of US China trade tensions and has accelerated with new tariff threats. Vietnam offers tariff relief on many shipments to the United States and Europe, a large pool of young workers, and geography that keeps suppliers in southern China within trucking distance.

- A manufacturing shift gathers pace

- Why Vietnam is attracting factories

- Tariffs and rules are reshaping sourcing plans

- Sectors on the move

- The hidden costs and bottlenecks

- Vietnam and China remain closely linked

- Local impacts, from jobs to new consumer markets

- Risk watch and strategy for companies

- What to Know

Companies that once anchored in Guangdong or Zhejiang are now booking flights to Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. A Dongguan electronics maker that makes plastic casings moved to Bac Ninh after clients insisted shipments avoid higher US duties on China, a pattern repeated across sectors from apparel to appliances. Northern provinces such as Bac Ninh and Bac Giang now host Samsung smartphone plants and suppliers to Apple and Canon. Proximity to China reduces transit times for parts, helping factories meet tight delivery windows.

The gains come with pressures. Rents in industrial parks have climbed, wage floors are rising, and productivity still trails China’s best in class plants. Many goods still rely on Chinese components, a dependency that complicates tariff classifications and exposes firms to changing rules of origin. Even with these frictions, Vietnam remains compelling because tariffs on Vietnamese goods are generally lower than on goods shipped directly from China, and because free trade deals give exporters a path into high value markets.

Why Vietnam is attracting factories

The appeal starts with cost, location, and market access. Vietnam sits next to China, with highways and border gates that allow parts to move quickly across the frontier. Labor costs remain lower than in China’s coastal manufacturing hubs. The government has upgraded ports and roads, set up industrial parks, and offered tax holidays and incentives designed to pull in foreign direct investment.

Trade access and government incentives

Vietnam is party to a web of free trade agreements (FTAs) that give it preferential access to major consumer markets. These include the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the EU Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA). According to Vietnam Briefing, the country counts 16 active FTAs and more than 80 double tax avoidance agreements, which reduce tax burdens and encourage cross border investment. The EVFTA lowers import duties over several years and promotes closer alignment with European standards in sectors such as pharmaceuticals and motor vehicles. This opens doors for firms that assemble in Vietnam to ship into the EU without the surcharges many Chinese made products face.

Investment has followed. Registered FDI totaled about 38.23 billion US dollars in 2024, with manufacturing and processing leading the flows. Caixin Global reports that by April 2025, newly approved foreign investment rose 39.9 percent from a year earlier to 13.82 billion US dollars, with almost 9 billion destined for manufacturing and 2.83 billion for real estate. Industrial park development has expanded to 416 parks, with plans to add or enlarge hundreds more by 2030. That policy push is a major reason global brands from Samsung and LG to Foxconn and Adidas chose Vietnam for new capacity.

Geography, workforce, and the China plus one playbook

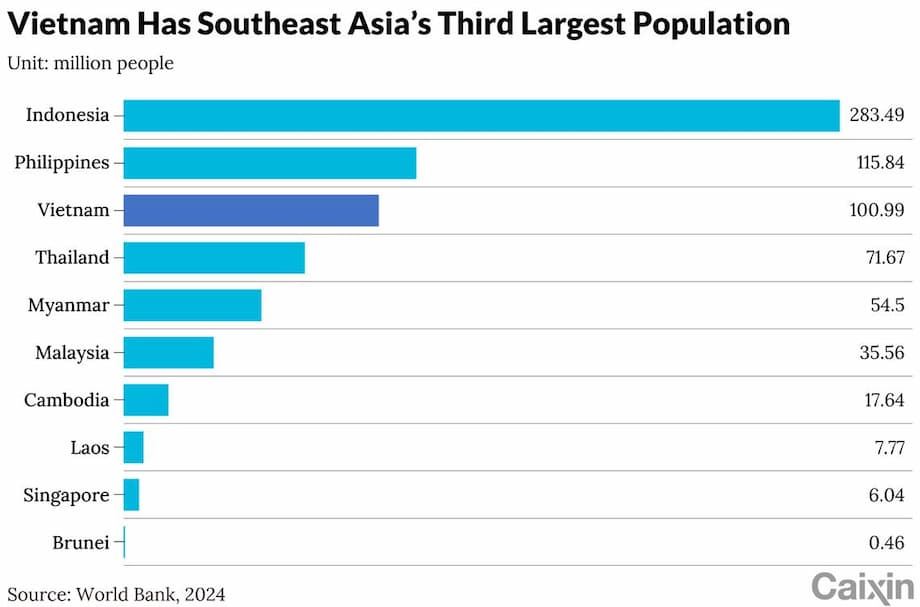

Vietnam’s location enables a China plus one strategy, where companies keep part of their supply base in China while shifting significant assembly steps to nearby countries. Northern Vietnam lies a short drive from factories across the border in Guangxi and Yunnan, which helps stabilize supply lines. Vietnam also has a large and increasingly skilled workforce. Government training programs have expanded, and multinational manufacturers have created in house academies to raise quality and speed. A growing middle class and political stability add to the appeal for long term investors.

Tariffs and rules are reshaping sourcing plans

Trade policy shocks have become the main catalyst. The New York Times reported in May 2025 that high US tariffs on China pushed many Chinese companies to move production or assembly abroad, with Vietnam the standout destination. Some factories relocated quickly to keep shipping to American customers without the penalty rates that now hit China. The rush has drawn in e commerce platforms and procurement agents, who help coordinate moves or reroute supply to Vietnamese sites.

Policy remains fluid. Rest of World reported that Washington announced a new set of reciprocal tariffs that would include a 46 percent levy on imports from Vietnam, but also granted a 90 day window for negotiations. Earlier reporting indicated that tariffs on many Vietnamese goods were paused for a time, which spurred a surge in orders to plants around Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi. Consultants in Vietnam say Chinese companies continue to file for licenses and rent space, looking to hedge policy risk while keeping close to their supplier networks.

Winnie Lam, a business consultant in Ho Chi Minh City quoted by the South China Morning Post, cautioned that the benefits are real but could shift with politics.

Vietnam is still benefiting from Trump 1.0, but we do not know for how long.

Fashion giant Shein, according to Inside Retail Asia, has offered temporary incentives to Chinese suppliers who move part of their production to Vietnam, including higher procurement prices and larger order guarantees. That push mirrors a broader trend. Firms in toys, apparel, and consumer electronics are using Vietnam as a second base. Some are transferring equipment from Chinese sites, while others are building new lines in Vietnamese industrial parks.

Sectors on the move

Vietnam’s manufacturing boom is not uniform. Electronics, apparel, toys, and semiconductors each tell a different story about what is moving, what is staying, and where the bottlenecks lie.

Electronics and smartphones

Samsung’s decision to build major smartphone capacity in Vietnam more than a decade ago set the template. Most Samsung smartphones are now made in Vietnam. Apple’s suppliers have expanded in Bac Giang and Bac Ninh, building components and assembling devices such as AirPods and Apple Watches. Foxconn, Luxshare, Goertek, and other Chinese tech firms have invested in northern Vietnam to follow client orders.

Production still relies heavily on imported parts from China and South Korea. That link is strategic. It allows fast access to displays, optics, batteries, and precision components that Vietnam does not yet make at scale. The dependence can complicate compliance with rules of origin in trade agreements and can trigger anti circumvention scrutiny in the United States when the value added in Vietnam is small relative to imported content.

Vietnam’s factories learned to operate under strain during the pandemic. In 2021, the government allowed key electronics plants to keep running under strict health protocols, and workers in some sites lived on premises to prevent outbreaks. The sector faced a downturn in 2023 as global demand softened, with tens of thousands of layoffs reported early in the year. Hiring rebounded in 2024 and 2025 as orders improved, and competition for skilled workers increased wages and bonuses.

Semiconductors and the rise of back end manufacturing

Vietnam is gaining ground in assembly, testing, and packaging of chips, the back end of the semiconductor chain. Tom’s Hardware reports that Amkor is building a 1.6 billion US dollar campus in Vietnam that will be the company’s largest and most advanced site. Intel operates its biggest back end facility near Ho Chi Minh City. South Korea’s Hana Micron is expanding investments in chip packaging, and local companies such as FPT plan a testing plant coming online in 2025. The government has set an ambition to have at least six semiconductor fabs by 2050.

Back end manufacturing is labor intensive and capital light compared to wafer fabrication, which requires ultra clean rooms and extreme precision. Vietnam can scale packaging and testing with training and imported tools. Tom’s Hardware notes that Vietnam’s share of the global assembly and packaging market could rise from roughly 1 percent to near 8 or 9 percent by the early 2030s if planned investments land. US policy could amplify the trend, since parts of the CHIPS Act investment program are being steered toward partnerships in friendly countries. Even with momentum, Vietnam remains a small player in front end chipmaking, and plans for domestic foundries will take years to materialize.

Apparel and fast fashion

Vietnam has long been a powerhouse in garments and footwear, producing for brands such as Nike and Adidas. Chinese factories facing higher tariffs on US shipments have turned to Vietnam to finish or assemble orders, a reshoring tactic described by the New York Times. E commerce platforms and logistics agents have helped re route supply chains to Vietnamese cut and sew lines. The model faces challenges because fabric and trims still often come from China. That means a high share of imported content in finished apparel, which can limit tariff relief if rules of origin require yarn forward or fabric forward sourcing for preferential treatment.

Toys and consumer goods

The toy sector illustrates how fast a shift can occur once tariffs hit. Reuters reported that MGA Entertainment, a major supplier to Walmart and Target, plans to move 40 percent of its manufacturing to India, Vietnam, and Indonesia within months. About 77 percent of toys bought in the United States are currently made in China. As production moves, companies warn of price increases on remaining China made items. Vietnam is one of several destinations, and the country has attracted toy makers to industrial parks near both major cities. The sector benefits from Vietnam’s experience in plastics, textiles, and electronics assembly, which can be combined in modern toys.

The hidden costs and bottlenecks

Relocation has not been cheap. Caixin Global reports that industrial land rents in Vietnam are rising at roughly 6 percent per year, and can exceed prices in mainland China. Approval processes for new projects can be complex, infrastructure projects are not always aligned across regions, and land acquisition takes time. Vietnam’s land tenure system also differs from China’s, which puts more decision making in the hands of developers and can lengthen timelines.

Companies encounter hardware costs, training needs, and productivity gaps. BW Industrial, a major developer cited by Caixin Global, notes that relocation surprises many operators. Labor is less expensive, but output per worker can be lower until plants and teams learn each other’s processes. Wages are increasing 6 to 7 percent per year as factories compete for operators and supervisors. Vietnam Briefing and Supplyia’s comparisons point out a clear trade off. China has deeper supplier ecosystems and quicker access to specialized materials. Vietnam can import those inputs from China quickly, yet that dependency adds shipping costs and complicates customs paperwork for origin claims.

These realities help explain why some Vietnamese made goods end up costing more than expected. Firms that moved from China to Vietnam under client pressure have seen margins squeezed by higher land rents, rising wages, and logistics adjustments. Many are betting that favorable tariffs and market access will offset these costs at scale. Others maintain parallel production lines in China to serve that market and to keep a foothold in the world’s most complete supply chain.

Vietnam and China remain closely linked

The surge of factories into Vietnam does not mean a clean break from China. Vietnam has become China’s largest trading partner within ASEAN, and bilateral trade neared 1 trillion US dollars in 2024. Much of Vietnam’s export growth is tied to imported Chinese components, especially in electronics and textiles. Analysts at the Carnegie Endowment have long noted that Vietnam’s gross exports contain a high share of foreign value added. That integration is a strength for speed and flexibility, yet it can trigger scrutiny in destination markets.

The United States has taken a tougher line on goods suspected of being transshipped through third countries without sufficient local transformation. That puts the spotlight on rules of origin, which determine whether a product qualifies for preferential tariffs under an FTA or for normal tariffs. In apparel, the difference between cutting and sewing imported cloth versus spinning yarn and weaving fabric locally can decide whether a shipment qualifies for a low tariff rate. In electronics, the threshold for substantial transformation depends on how much value is added in Vietnam and which tariff lines inputs and outputs fall under. Firms are hiring trade lawyers and customs experts to map production steps to the correct classifications.

Even with those complications, Vietnam’s position in global supply chains keeps strengthening. As multinational firms move final assembly lines to Vietnam, their tier two and tier three suppliers increasingly follow. The result is a new cluster economy within Southeast Asia. Factories across northern Vietnam gain from Chinese and Korean suppliers operating nearby, while central and southern provinces are attracting smaller component makers and logistics providers that expand local capacity.

Local impacts, from jobs to new consumer markets

The influx of factories has reshaped local economies. The Bac Ninh and Bac Giang corridor has drawn hundreds of thousands of workers, created small business ecosystems, and increased household incomes. During the 2023 downturn, layoffs hit hard in some plants, and many workers, especially women, took temporary work in services before returning to factories as hiring resumed. Employers have offered higher wages, sign on bonuses, and transportation stipends to win back experienced staff.

Vietnam’s demographic dividend, with a young workforce and high female participation, remains an asset for labor intensive sectors. Vietnam Briefing projects a rapidly growing middle class through 2030. That consumer base is large enough to attract investment aimed at the domestic market, not just exports. Chinese automakers such as Shineray Motors and Geely are expanding local assembly and tailoring products to Vietnamese preferences. The country has become both a production base and a battleground for market share among Asian brands.

Language and management practices are adapting. Many Vietnamese workers in factory towns are learning Mandarin to advance within Chinese owned suppliers. Domestic tech companies and universities are expanding programs in electronics, robotics, and quality management to support higher value work on the production line. These steps can lift productivity and help local suppliers close the gap with foreign owned peers.

Risk watch and strategy for companies

Vietnam’s rise comes with risks that require active management. Tariff policy is unsettled in the United States, with potential new levies on Vietnamese goods under review and a 90 day negotiation period reported by Rest of World. Rules of origin are tightening in many markets, which raises the bar for how much local content is required to qualify for preferential rates. Enforcement against perceived transshipment has increased, particularly in textiles and electronics. Policymakers in Europe and the United States are also focusing on supply chain transparency and environmental standards, which will drive more audits and reporting.

Scale is another constraint. Vietnam’s labor force is a fraction of China’s. Research from the Carnegie Endowment suggests that Vietnam can absorb a subset of activity shifting out of China, but not everything. That means producers will likely spread operations across several countries, with Vietnam as a core node. For many firms, the practical answer is a modular production strategy: place final assembly and test in Vietnam, co locate key suppliers where possible, and keep complex upstream processes in China, South Korea, or elsewhere until local capacity develops.

For companies planning moves, three steps reduce risk. First, invest early in local supplier development and training to raise yields and quality. Second, design products with clear origin strategies, so each build of materials can meet target market rules without last minute re engineering. Third, maintain redundant supply lines where feasible, a switch from just in time to just in case that Caixin Global describes as the new normal. These measures add cost, yet they help firms navigate a trade environment where policies can shift within a quarter.

What to Know

- Chinese manufacturers are relocating capacity to Vietnam to avoid higher US tariffs on China and to diversify risk, with Vietnam benefiting from proximity, lower labor costs, and multiple trade deals.

- Vietnam has expanded industrial parks and incentives, attracting major brands in electronics, apparel, and consumer goods, while FDI in manufacturing remains strong in 2024 and 2025.

- The tariff outlook is volatile: media reports describe paused tariffs on Vietnam for some categories, a potential 46 percent levy under review, and very high rates on China that triggered the shift.

- Electronics assembly leads the surge, supported by Chinese and Korean suppliers; chip packaging and testing are growing fast with multibillion dollar investments by Amkor, Intel, and others.

- Apparel and toys are moving too, but many inputs still come from China, which affects rules of origin and tariff treatment in the United States and Europe.

- Costs in Vietnam are rising, including industrial land rents and wages; productivity and supplier depth lag China, which can squeeze margins for relocated firms.

- Vietnam and China remain tightly linked through trade, with Vietnam importing large volumes of parts; enforcement against transshipment and stricter origin rules are shaping sourcing decisions.

- Local impacts include job growth, higher wages, and a larger consumer market that is drawing Chinese automakers to localize products for Vietnamese buyers.

- Companies are adopting modular, multi country production strategies and building compliance into product design to meet changing rules and maintain market access.