Why a popular pastime is facing scrutiny

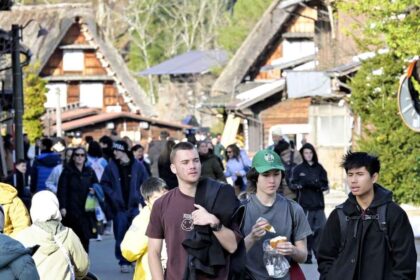

Wildlife cafes in Japan promise intimate encounters with owls, otters, meerkats, and other rare animals. A new undercover investigation by WWF Japan shines a harsh light on how those encounters are managed. The team visited 25 wildlife cafes in Tokyo, Chiba, and Kanagawa, and found widespread lapses in infection control and safety. Samples taken from animals detected 137 types of bacteria. Four cafes had enterohemorrhagic E. coli, two had Salmonella, and seven had antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus. At many sites, contact between people and animals occurred with few safeguards. Staff often encouraged hand sanitization on entry, but far fewer reminded customers to clean their hands when leaving, which is when pathogens can transfer from animals to people.

- Why a popular pastime is facing scrutiny

- Inside WWF Japan’s undercover survey

- What the bacteria findings mean for public health

- Injury risks and welfare in close contact settings

- Endangered species and the exotic pet pipeline

- Otter DNA clues point to trafficking routes

- Owl cafes and a booming trade

- How Japan regulates wildlife cafes compared to other countries

- What operators and visitors can do now

- Quick Facts

The survey counted 1,702 wild animals on display, including 459 endangered species. Cafes often featured animals that can bite or claw, including meerkats, but 19 of the 23 shops with higher risk animals had no barrier or steady staff supervision between visitors and those animals. The findings spotlight two concerns at once, human health and animal welfare. They also point to an expanding trade in exotic species. Japan hosts about 100 wildlife cafes, and its rules are looser than in South Korea, which outlawed wildlife cafes in 2023.

Inside WWF Japan’s undercover survey

WWF Japan, working with Hokkaido University’s Graduate School of Veterinary Medicine, checked what kinds of animals were present, how many, whether employees were stationed near animals, how exhibits were set up, and whether handwashing stations and sanitizers were installed. The tally of wild animals across the 25 locations shows how mainstream these attractions have become. Endangered species, including snowy owls and Asian small clawed otters, were present. In many rooms, visitors were able to pet, feed, or hold animals for a fee.

How the survey was done

Investigators recorded the presence or absence of barriers that would restrict visitors from reaching animals without staff mediation. Nineteen of the 23 shops displaying higher risk species lacked a barrier or steady supervision by employees. The team also looked for basic infection control. Eleven cafes had no handwashing station at all, and one had no hand sanitizer available. Staff at 23 venues encouraged sanitization on entry, but only 14 did so on exit, a gap that overlooks the very direction in which zoonotic infections move, from animals to humans.

What the bacteria findings mean for public health

The mix of bacteria reported in the survey includes well known causes of foodborne and contact infections. Enterohemorrhagic E. coli can release toxins that damage the lining of the gut and kidneys. In severe cases it triggers hemolytic uremic syndrome, which can be life threatening. Salmonella causes fever, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps, and spreads easily in environments where animals and people share surfaces. Antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus adds another layer of risk because some strains are difficult to treat once they enter cuts or the bloodstream. Young children, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems are more vulnerable to these infections.

Close proximity, repeated handling, and shared surfaces create many opportunities for bacteria to move between species. Cafes expose different animals to many visitors each day, which increases the chance that a pathogen can find hosts in which to persist. Detecting a pathogen in a sample does not mean people fell ill in that exact cafe, yet the presence of dangerous bacteria in multiple venues is a warning that routine operations lack basic controls.

Other recent observations support that concern. Researchers have documented cases in Japan of infections linked to contact with animals since 2000, including 12 cases of enterohemorrhagic E. coli, nine of Salmonella, and four of Cryptosporidium. In at least one venue, animals were seen entering areas where food and drinks were served, a practice that contradicts basic disease prevention guidance for petting settings. Handwashing after contact, bans on food in animal rooms, and clear separation of animal areas from dining areas are among the simplest and most effective steps to lower risk.

Injury risks and welfare in close contact settings

Injury prevention was also weak in many of the cafes surveyed. Species with sharp claws and bite force, such as meerkats and some birds of prey, were displayed in 23 cafes. In 19 of those, there was no barrier or constant supervision. Even minor scrapes or punctures raise infection risk, and animals can be harmed when overhandled or startled. Protective rules exist in many petting zoos to reduce stress on animals and prevent visitor injuries, such as time limits for handling, no-touch periods, and space buffers. The findings suggest many wildlife cafes lack such routines.

Welfare problems compound these risks. Many wildlife species are nocturnal, sensitive to light, and require space and enrichment to avoid stress. Owls are often surrounded by bright lights and frequent handling in cafes. Otters are semi aquatic, social, and highly active. Enclosures that are too small, diets that do not match natural needs, and constant public contact can create chronic stress. Stressed animals shed more pathogens and are more likely to bite or scratch when startled.

Mayumi Ishizuka, a professor of veterinary medicine at Hokkaido University who studies wildlife and public health, has described how unrealistic it is to keep wild owls in human settings if genuine welfare standards are applied. She reminded readers that a true owl habitat would be expansive and complex.

“First, please acquire several square kilometers of woodland… I hope you are rich.”

Her point is simple. Animals adapted to wide ranges, flight, and hunting at night cannot have those needs met by small rooms, endless handling, and bright lights. That mismatch is a welfare issue for the animals, and it raises human safety risks at the same time.

Endangered species and the exotic pet pipeline

The survey identified 459 endangered animals among the 1,702 individuals observed. WWF Japan warned that the display and sale of rare species can fuel demand and push markets toward overexploitation. Some cafes do not only display animals, they also sell them. Prior research has cataloged dozens of establishments offering animals for purchase. When direct sales sit alongside paid handling, the setup can normalize wild species as pets and turn a day out into an impulse buy.

Academic surveys of exotic animal cafes across the country show how diverse this market has become. One study counted 3,793 animals from 419 species across 142 establishments. Birds dominated, and owls alone accounted for a large share. Reptiles and small mammals rounded out most of the rest. Many species were listed under CITES, which regulates international wildlife trade, and some were invasive species that can harm local ecosystems if released. Japan lacks a comprehensive, specialty licensing system tailored to exotic animal cafes, and existing rules do not always require robust proof that animals are legally sourced and captive bred. Gaps in oversight make laundering of wild caught animals easier.

Otter DNA clues point to trafficking routes

New genetic research has linked otters in Japanese cafes to poaching hotspots in southern Thailand. Scientists analyzed DNA from 81 captive otters in Japan, including individuals held in cafes, zoos, and government seizures, and compared these profiles with wild otter populations in Southeast Asia. Over 90 percent of the cafe and seized otters matched the genetic signatures of Thai populations known for illegal capture. The Asian small clawed otter was moved to CITES Appendix I in 2019, which bans commercial international trade, yet traffickers continue to exploit weak spots in regulation and enforcement across source and transit countries. Online ads and social media make it easier to reach buyers, and past seizures show live otters still moved on passenger flights.

Beyond law enforcement, the wildlife biology is also a red flag. Otters are high energy, social, and need ample water and space. In captivity, they often display repetitive or anxious behaviors when kept in small enclosures or separated from compatible groups. When demand grows for such animals in cafes, the shift can lead to more smuggling and more animals confined in settings that do not meet their needs.

Owl cafes and a booming trade

Owls are among the most visible faces of this trend. Research conducted by Monitor, TRAFFIC Japan, WWF Japan, and Copenhagen Zoo found 1,914 owls from 49 species in 92 establishments, with import records showing that a growing variety of species has entered the market. Ninety percent were non native to Japan. The dataset included two Near Threatened species and one Vulnerable species. Seizure records from 2012 to 2021, most in Japan and some in Southeast Asia, documented at least 62 owls of eight species confiscated in 17 incidents. Even when an owl is sold as captive bred, paperwork can be hard to verify, and lines blur if parent stock was originally taken from the wild without proper permits.

Traceability is the critical missing piece. Trade codes, mislabeling, selective breeding, and outdated taxonomy can muddle the true identity and origin of birds. Without reliable records that follow an individual from breeder to importer to shop, regulators and buyers cannot know with confidence where each owl came from. Conservation groups argue for stronger documentation requirements, regular audits, and better data sharing to close those gaps.

How Japan regulates wildlife cafes compared to other countries

Japan’s legal framework includes animal welfare and infectious disease laws, but it does not set out a standard system tailored to cafes that display or sell wild animals with direct visitor contact. WWF Japan has called for a system in which qualified experts review which species can be displayed, how they should be housed, and whether direct handling should be permitted at all. Routine on site inspections and staff training would be part of that system.

Other countries have taken stronger steps. South Korea banned wildlife cafes in 2023. Many jurisdictions require licensing for animal encounters, infection control plans, staff qualifications, and separation between animal areas and spaces where food and drink are served. Handwashing stations at exits, visible signage, and rules against allowing animals into dining areas are basic measures in those systems.

Public health and welfare experts often recommend a few grounding principles. The list includes a ban on direct handling of higher risk species, a clear barrier between visitors and animals that can injure, hands off periods to reduce stress, record keeping that proves legal origin, and routine veterinary checks. Those steps reduce disease risk and help prevent harm to animals and people.

What operators and visitors can do now

Policy change can take time. In the meantime, cafes and visitors can cut risk by focusing on practical steps that are already common in safe animal contact settings. Cafes can review their room layouts, add barriers where needed, and make sure staff are always present when visitors are near animals. Managers can place handwashing stations at exits, separate animal rooms from dining, and stop allowing animals to enter areas where food and drinks are served. Clear signage and reminders to clean hands as people exit reduce the chance that bacteria leave with them.

- Cafes should install handwashing stations at exits and keep sanitizer visible in all animal rooms.

- Staff should supervise all visitor interactions with animals that can bite or scratch.

- Food and drink should never be served in rooms where animals are roaming.

- Stop direct handling of higher risk species and limit handling time for others.

- Keep detailed records that show legal origin and species identity for every animal.

- Provide lighting, space, and enrichment appropriate to each species, especially for nocturnal birds.

Visitors can also reduce risk. Choose venues that post their hygiene rules and species list, and that place clear boundaries between visitors and animals. Wash or sanitize hands after every interaction and again when leaving. Avoid touching your face, any cuts, or your phone until after washing. Do not feed animals unless instructed by trained staff using food they provide. Avoid buying exotic pets or booking private handling sessions if welfare standards appear weak.

- Look for barriers, staff presence, and handwashing options before you enter.

- Wash hands after contact and again on exit, especially before eating.

- Skip venues that let animals enter dining areas or lack clear hygiene rules.

- Do not encourage friends or children to handle animals that appear stressed.

- Do not purchase exotic pets on impulse after a cafe visit.

Quick Facts

- WWF Japan surveyed 25 wildlife cafes in Tokyo, Chiba, and Kanagawa.

- Investigators counted 1,702 wild animals, including 459 endangered individuals.

- Samples detected 137 bacteria types, including E. coli and Salmonella.

- Four cafes had enterohemorrhagic E. coli, two had Salmonella, seven had antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus.

- Eleven cafes lacked handwashing stations, and one had no hand sanitizer.

- Staff encouraged sanitization on entry at 23 venues, but only 14 did so on exit.

- High risk animals were displayed in 23 cafes, and 19 lacked barriers or steady supervision.

- Japan hosts about 100 wildlife cafes, while South Korea banned them in 2023.

- DNA analysis linked over 90 percent of tested cafe and seized otters in Japan to Thai poaching hotspots.

- Research documented 1,914 owls from 49 species in 92 establishments, 90 percent non native.