Unrest in Kediri spills into cultural loss

Hours of violent protests in Kediri, East Java, ended with a ransacked local museum and missing heritage objects. During a weekend of anti government anger, crowds broke into the Bagawanta Bhari Museum and stole a fragment of a Ganesha statue from the tenth century, along with heritage textiles and other items, local officials said. The break in unfolded as protesters torched parts of the regency government complex and police posts near the museum site. Police later arrested scores of people and began checking footage and witness accounts.

- Unrest in Kediri spills into cultural loss

- What drove the protests and how Kediri became a flashpoint

- Why the Ganesha head matters to history and identity

- The hunt for the stolen items

- Museums tighten security, archaeologists issue warnings

- How protests spill into heritage damage

- What the law says about theft and damage

- What damage the objects might face and how experts respond

- Key Points

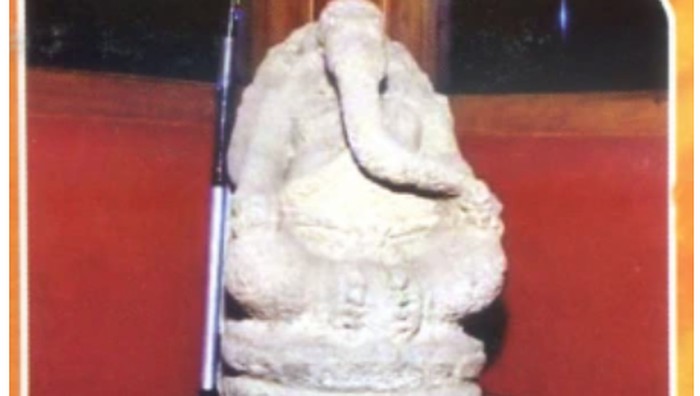

Authorities said the missing Ganesha piece is a 30 centimeter fragment of the statue’s head discovered by archaeologists in 2009 in Babadan village in Kediri. Specialists have connected the object to the ancient Mataram Kingdom, a Javanese Hindu and Buddhist power active between the eighth and tenth centuries. The fragment helped identify a ruined structure in Babadan as a Hindu place of worship. A Buddhist statue was also found in the same area, which archaeologists cite as evidence of past coexistence in the region.

Museum staff and officials described more losses. Four pieces of batik cloth with Kediri specific motifs were taken. A miniature model of a traditional rice barn and another statue on display were destroyed. The batik was especially sensitive because the cloth served as a prototype for formal Kediri attire. Staff were able to carry three items to safety as crowds approached, including the museum’s most valuable piece, a tenth century head of a Buddha statue, and two inscribed bricks with mantras that are still under study. The museum sits directly behind the Regional Legislative Council building, which was also attacked.

What was taken and damaged

Local authorities and museum staff provided the following account of losses and evacuations during the raid and its aftermath.

- Missing: a 30 centimeter fragment of a Ganesha head from the tenth century, found in Babadan in 2009.

- Missing: four batik textiles carrying unique Kediri motifs that serve as design prototypes for official attire.

- Destroyed: a miniature model of a traditional rice barn and another statue on display.

- Evacuated to safety: a tenth century head of a Buddha statue and two mantric inscribed bricks for ongoing research.

Officials in Kediri have distributed flyers and opened a channel for the safe return of artifacts. Appeals urge anyone who took or now holds the objects to return them without fear of confrontation. The goal is to stabilize and preserve heritage items before they are harmed by mishandling or illicit resale.

What drove the protests and how Kediri became a flashpoint

The museum raid came during nationwide protests that started in Jakarta, where outrage over lawmaker allowances grew into a larger movement. Demonstrators accused parliament members of extravagance during tough economic times. Anger intensified after a police vehicle ran over and killed a 21 year old motorcycle taxi driver in the capital. Vigils and marches evolved into a campaign against police violence in several cities.

By the weekend, unrest had reached Kediri. Crowds set fire to the Regional Legislative Council building, the regency administration office, and several police stations. The Bagawanta Bhari Museum, located behind the council building, was left exposed as security forces struggled to contain attacks across the complex. In the chaos, a group forced its way into the museum. That is when the Ganesha fragment, batik textiles, and other items disappeared or were destroyed.

Kediri Police said they have detained 123 people in connection with the weekend events. Those taken into custody include junior and senior high school students and several women. Investigators are reviewing each case, building files, and weighing potential charges for those with evidence against them. The National Commission on Human Rights has reported at least 10 deaths since the first protests broke out. Some deaths are alleged to involve violent acts by security personnel during or after demonstrations.

Why the Ganesha head matters to history and identity

Ganesha, the elephant headed deity of wisdom and learning, is a central figure in Hindu art across the Indonesian archipelago. Stone images of Ganesha appear in temples and ancient sites throughout Java and Sumatra, part of a long tradition that spans many centuries. The missing fragment embodies that tradition. Even as a single piece, it anchors a specific place and time in Kediri’s landscape.

Archaeologists connect the fragment to the ancient Mataram Kingdom. Mataram governed parts of Java between the eighth and tenth centuries, and it produced temples, inscriptions, and sculpture that define early Javanese art. Finding the Ganesha head in Babadan helped researchers confirm a Hindu sanctuary was present there. The nearby discovery of a Buddhist statue showed that different religious traditions existed side by side in this area in the same period. That is why the Ganesha fragment is treated as more than a broken stone. It is a key to a local story about art, belief, and community.

Textiles taken during the raid carry their own weight. Batik is both art and heritage in Indonesia, with each region producing patterns and dye practices that say something about local identity. Kediri’s motifs serve as a guide for ceremonial attire. The loss of those prototype cloths is not just a missing museum case item. It sets back documentation and design work that feed living traditions in the regency.

The hunt for the stolen items

The Kediri administration has asked anyone who holds museum property to return it quickly and quietly. Flyers around the regency and online messages explain how to reach local officials to arrange a safe handover. The museum and the Tourism and Culture Office have secured the remaining collection. Teams are cataloging damage, checking storage, and preparing condition reports. Police are tracing leads from videos, photos, and tips. Investigators are also monitoring physical markets and online listings where heritage objects sometimes surface soon after unrest.

Hanindhito Himawan Pramana, the regent of Kediri, appealed directly to the public. He asked those who took objects, or anyone who recognizes them in circulation, to come forward so the items can be protected and studied.

The regency sincerely hopes these treasures are returned. Cultural heritage holds immense historical value and should never be a target of looting.

Museum teams are asking members of the public not to clean, glue, or otherwise handle any object they plan to return. Stone sculpture can chip, weather, or crack if exposed to heat or chemical cleaning. Batik dyes respond poorly to detergents and bright light. A hurried attempt to restore an object can cause permanent loss. If returns occur soon and with care, conservators will stabilize stone and textiles, then rehouse them in controlled storage while the building is repaired.

Museums tighten security, archaeologists issue warnings

Concerns from the heritage community rose after the Kediri raid. The Indonesian Archaeologists Association (IAAI) circulated a statement calling for stronger protection of museums and historic buildings during periods of unrest. The group said cultural heritage is a national legacy with historical, scientific, educational, and cultural value, and that it represents identity and unity across the archipelago.

IAAI leaders also underscored that international rules protect culture even in severe crises. The general chairperson, Marsis Sutopo, pointed to a core principle of the 1954 Hague Convention, which is a benchmark for safeguarding art and heritage in conflict.

The 1954 Hague Convention prohibits the destruction of cultural heritage, even in times of war.

Museums in Jakarta are recalibrating security as well. The National Museum of Indonesia announced a temporary closure starting September 1 to allow tighter supervision of its large collection. The institution, which holds more than 140 thousand objects ranging from manuscripts to classical stone, said security and monitoring procedures are being strengthened during the pause. Other public institutions near protest routes have also limited access or suspended visits while the situation settles.

How protests spill into heritage damage

When street protests move fast and police redeploy to multiple flashpoints, cultural sites can become vulnerable. Many local museums sit inside or next to government compounds. If crowds breach a gate, the same route can lead to galleries and storage rooms. In Kediri, the Bagawanta Bhari Museum stands behind the legislative building that was set on fire. Once that perimeter failed, the museum saw an influx of people and a mix of looting and vandalism.

Looting is often opportunistic. It is not always driven by collectors or traffickers, though stolen art sometimes moves into illegal networks later. Small stone fragments and portable textiles are easier to carry off than large statues or architectural pieces. The risk to research and education is real. When a museum loses context, labels, and associated notes, the value of an object for study drops sharply.

Indonesia has suffered heritage losses before, from theft to fire. In 2023 a fire damaged parts of the National Museum in Jakarta, leading to months of restoration. Those episodes taught curators to prepare inventories, create emergency plans, and train staff in evacuation techniques. The Kediri raid will add to that playbook. It will likely trigger drills, storage upgrades, and closer coordination with police during periods of tension.

What the law says about theft and damage

Indonesia’s Cultural Heritage Law No. 11 of 2010 treats theft, destruction, and illegal trade of heritage as serious crimes. Courts can impose prison and fines, and they can order the recovery of objects that surface in private hands. Police often work with provincial culture offices to document losses. Customs officers and border guards receive alerts to intercept items that match descriptions in museum logs.

Law enforcement also relies on provenance, the chain of custody that shows where an object came from and who has held it. Museums keep photos, measurements, and condition notes. These records strengthen criminal cases and help officers identify objects if they appear in sales. Public awareness can help as well. Clear photos and plain language descriptions of missing items increase the chance that a market dealer, courier, or neighbor will recognize a piece and make a report.

What damage the objects might face and how experts respond

The missing Ganesha fragment is likely carved from volcanic rock common in Java. Stone of this kind is resilient, yet it can suffer chips, scratches, and staining from smoke or household chemicals. Repeated handling can abrade decorative details. If the fragment is kept in a dry, dusty environment, salts can bloom on the surface and cause flaking. Conservators use soft brushes, distilled water, and controlled drying to stabilize stone after incidents like this.

The stolen batik cloth is fragile. Natural dyes can fade in sunlight or bleed if cleaned with soap. Folding and creasing cause stress lines that lead to tears. Professionals lay textiles flat, support them on acid free materials, and regulate humidity to prevent mold. Quick return gives conservators the best chance to clean soot and reinforce weak fibers before damage becomes permanent.

If the artifacts are returned soon, the museum can perform a full condition survey. That process documents every loss and repair. It helps courts, insurers, and the public understand what happened. It also guides future exhibit planning and research access once security is stable and the building is ready to reopen fully.

Key Points

- Protests in Kediri, East Java, spilled into the Bagawanta Bhari Museum, leading to theft and damage.

- A 30 centimeter Ganesha head fragment from the tenth century is missing, along with four Kediri batik textiles.

- A miniature rice barn model and another statue were destroyed, while a tenth century Buddha head and two inscribed bricks were saved.

- Kediri Police detained 123 people and are reviewing evidence to bring charges where warranted.

- The unrest is part of a nationwide movement that began over lawmaker allowances and escalated after the death of a motorcycle taxi driver in Jakarta.

- The Kediri regent urged looters to return the items and opened a channel for safe handover.

- The archaeologists association warned that heritage must be protected during unrest and cited international rules that forbid its destruction.

- The National Museum of Indonesia in Jakarta temporarily closed to tighten security of its collection.

- Experts say quick, careful returns will give conservators the best chance to stabilize stone and textiles.