US Cracks Down on Southeast Asia’s Role in China Trade War

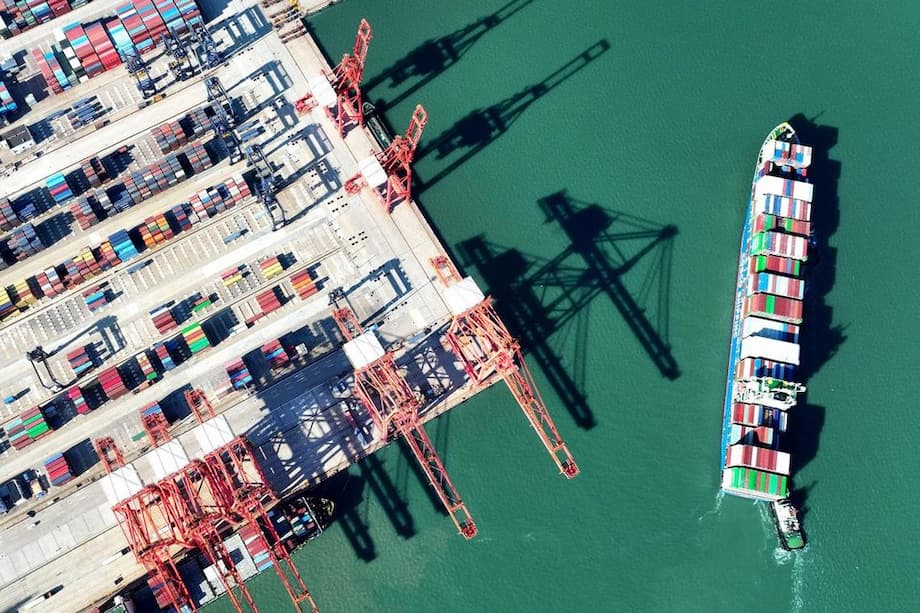

The United States has intensified its efforts to curb what it sees as loopholes in its trade war with China, turning its focus to Southeast Asia’s booming transshipment trade. President Donald Trump’s administration, after years of complaints, is now pressuring countries like Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore to clamp down on Chinese exporters allegedly using their territories to dodge US tariffs. This move marks a significant escalation in the ongoing US-China trade conflict, with far-reaching implications for global supply chains, regional economies, and the future of international trade norms.

- US Cracks Down on Southeast Asia’s Role in China Trade War

- What Is Transshipment and Why Does It Matter?

- Southeast Asia’s Dilemma: Balancing Prosperity, Neutrality, and Compliance

- China’s Response: Deepening Integration with ASEAN

- Uncertainties Remain: Rules of Origin and Enforcement Challenges

- Broader Economic and Strategic Implications

- In Summary

At the heart of the issue is the practice of transshipment—the routing of goods through third countries to disguise their true origin and avoid punitive tariffs. As the US has imposed sweeping tariffs on Chinese goods, Chinese firms have increasingly routed exports through Southeast Asian countries, exploiting jurisdictional and regulatory gaps. This has not only challenged US trade enforcement but also put Southeast Asian economies in a delicate position, caught between two economic giants.

What Is Transshipment and Why Does It Matter?

Transshipment is a logistics strategy where goods are shipped to an intermediate country before reaching their final destination. In theory, this can be a legitimate part of global supply chains, especially in regions with integrated manufacturing. However, in the context of the US-China trade war, transshipment has become a tool for tariff evasion. Chinese exporters ship goods to Southeast Asian countries, where they are relabeled or undergo minimal processing, and then exported to the US as products of those countries, thereby avoiding higher tariffs imposed on Chinese goods.

This practice has drawn sharp criticism from US officials. According to The Diplomat, the US Commerce Department has ruled that solar modules assembled in Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam with Chinese inputs violated US trade laws. Similarly, Vietnam has intercepted thousands of shipments falsely labeled as “Made in Vietnam” but traced back to Chinese factories.

For Southeast Asia, the stakes are high. The region’s economic success has long relied on openness to trade and efficient logistics. However, the growing scrutiny over transshipment threatens this openness, as external regulations and enforcement measures clash with free trade norms and regional economic integration.

How US Tariffs Are Reshaping Trade Flows

Since the start of the US-China trade war in 2018, the US has imposed tariffs ranging from 10% to over 40% on Chinese goods. In response, Chinese exports to countries like Vietnam have surged, with Vietnam’s imports from China growing at an annual rate of nearly 19% between 2018 and 2024. At the same time, Vietnam’s exports to the US have nearly tripled, closely mirroring the increase in Chinese imports—a strong indication of transshipment activity.

To counter this, the US has embedded strict rules of origin and higher tariffs for transshipped goods in its trade deals with Southeast Asian countries. For example, under a recent US-Vietnam agreement, direct Vietnamese exports to the US are subject to a 20% tariff, but goods deemed to be transshipped from China face a 40% tariff. Similar provisions are being negotiated with Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand.

However, enforcing these measures is complex. Many Southeast Asian factories rely on Chinese components, making it difficult to distinguish between legitimate manufacturing and mere relabeling. The lack of clear rules of origin and the intricacies of integrated supply chains further complicate enforcement.

Southeast Asia’s Dilemma: Balancing Prosperity, Neutrality, and Compliance

Southeast Asian countries now face a delicate balancing act. On one hand, they seek to maintain economic prosperity and neutrality in the US-China rivalry. On the other, they must avoid becoming conduits for regulatory evasion, which could erode trust with major trade partners and compromise their autonomy in shaping future trade and technology governance.

Policy responses across the region reflect this tension. Vietnam, for instance, has agreed to stricter penalties for illegal transshipment and trade fraud, focusing inspections on Chinese products and introducing new decrees to monitor companies that self-certify product origins. Malaysia and Thailand have also pledged to clamp down on tariff-dodging, with customs authorities increasing audits and monitoring for illegal imports.

Despite these efforts, analysts remain skeptical about the effectiveness of enforcement. As reported by the South China Morning Post, the rapid surge in Chinese investment into Southeast Asia and the complexity of global supply chains make it difficult to fully prevent transshipment. Some experts argue that as long as there are opportunities for profit, businesses will find ways to circumvent tariffs, legally or illegally.

Regional Trade Agreements and the Role of RCEP

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a major free trade agreement among Asia-Pacific nations, has further facilitated regional trade by reducing tariffs and streamlining customs procedures. While this has boosted economic integration, it has also made it easier for goods to move across borders, complicating efforts to enforce US tariffs and rules of origin.

For Southeast Asian countries, the challenge is to build resilience and regulatory frameworks that uphold openness and integrity, while safeguarding their neutrality and economic interests. This includes strengthening cross-border coordination, improving disclosure requirements, and co-developing export control mechanisms that reflect regional priorities.

China’s Response: Deepening Integration with ASEAN

China, for its part, has responded to US pressure by deepening its economic ties with Southeast Asia. Chinese officials and economists have urged Chinese firms to integrate more fully with local economies in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), rather than simply using the region as a transshipment route. This strategy aims to protect Chinese exports from unpredictable tariff rates and to consolidate China’s position as ASEAN’s top trade partner.

According to customs data, goods trade between China and ASEAN reached nearly $1 trillion in 2024, up almost 8% from the previous year. President Xi Jinping has also embarked on diplomatic tours of the region, urging countries to join China in defending free trade and warning against the dangers of protectionism. However, Southeast Asian nations remain cautious, seeking to appease both Washington and Beijing to avoid being caught in the crossfire of the trade war.

Geopolitical Implications and the Future of Supply Chains

The US crackdown on transshipment is not just about tariffs—it is part of a broader contest for global supply chain dominance. By targeting Southeast Asia’s role as a transshipment hub, the US aims to force a geographic restructuring of trade, encouraging companies to relocate manufacturing out of China and into other countries. However, full decoupling is unlikely. Instead, global supply chains are becoming more fragmented, with China supplying components and Southeast Asia handling assembly for US-bound exports.

This fragmentation has increased compliance costs for manufacturers and banks, forced companies to invest in digital tools to track trade flows and verify product origins, and spurred demand for trade financing and cross-border services. For Southeast Asian banks like OCBC, this new environment has required tighter credit risk buffers, cost discipline, and a pivot to high-growth sectors less exposed to US-China volatility.

Uncertainties Remain: Rules of Origin and Enforcement Challenges

Despite the flurry of new trade deals and tariff announcements, key details remain unresolved. The US has yet to finalize the rules of origin that will determine what constitutes a transshipped product. This uncertainty has left Southeast Asian exporters and policymakers in a state of limbo, unsure how to avoid punitive rates that target China’s supply chains.

For example, Thailand’s Finance Minister has argued that local content should exceed 40% for a product to be classified as Thai, but no agreement has been reached with the US. Similarly, Vietnam’s government is waiting for clarification on how Washington will define illegal transshipment and the value that must be added to imported products to avoid the 40% tariff.

Experts warn that the lack of clarity could undermine the effectiveness of US measures and create new opportunities for trade diversion. As one analyst told Bloomberg, “The punitive tariff may have little impact on China or its manufacturers’ ability to reach American buyers, as enforcement will be challenging and trade diversion may continue to reduce the effect of US tariffs on China’s exports.”

Broader Economic and Strategic Implications

The US-China trade war and the crackdown on transshipment have far-reaching implications for the global economy. For Southeast Asia, the risks include:

- Potential loss of export competitiveness if US tariffs and compliance costs rise

- Strained relations with both the US and China, making it harder to maintain neutrality

- Pressure to upgrade regulatory frameworks and customs enforcement, which may be costly and complex

- Opportunities to attract genuine foreign investment and move up the value chain, if companies relocate manufacturing to the region

For China, the challenge is to adapt to a more fragmented global trading system and to deepen integration with key partners to offset the impact of US tariffs. For the US, the effectiveness of its strategy will depend on its ability to enforce new rules and maintain alliances with Southeast Asian countries, even as it pushes them to take sides in the broader geopolitical contest.

Ultimately, the future of global supply chains will be shaped by how these competing pressures are managed. Southeast Asia’s role as a trade hub is likely to remain central, but the region will need to assert a coherent strategy that balances openness, integrity, and resilience in the face of external shocks.

In Summary

- The US has intensified its crackdown on transshipment through Southeast Asia to prevent Chinese goods from dodging tariffs.

- Southeast Asian countries are under pressure to strengthen customs enforcement and regulatory frameworks, but face challenges due to integrated supply chains and economic reliance on both the US and China.

- China is deepening its integration with ASEAN to protect its exports and maintain its role as the region’s top trade partner.

- Uncertainties remain over the rules of origin and enforcement of new US tariffs, creating risks and opportunities for regional economies.

- The broader contest for supply chain dominance is reshaping global trade, with Southeast Asia at the center of these shifting dynamics.