The Complex Journey Home: Why Reintegration Is So Challenging for Returning Migrant Workers

For millions of migrant workers across Asia and beyond, the decision to leave home in search of better opportunities is often driven by necessity. Yet, the journey does not end when they return. Instead, many face a new set of challenges—emotional, social, and economic—that can be as daunting as the migration itself. The stories of Ayu Rosita from Indonesia and Faye Miranda from the Philippines, among countless others, highlight the profound difficulties of reintegrating into their home communities after years abroad.

- The Complex Journey Home: Why Reintegration Is So Challenging for Returning Migrant Workers

- What Awaits Migrant Workers Upon Return?

- Psychosocial and Emotional Challenges: More Than Just Homesickness

- Economic Hurdles: From Breadwinners to Job Seekers

- Government and Community Responses: Are They Enough?

- Structural and Policy Barriers: The Need for a Holistic Approach

- Gendered and Vulnerable Groups: Who Faces the Greatest Risks?

- Lessons from Around the World: Comparative Perspectives

- The Broader Picture: Migration, Development, and the Future

- In Summary

As global migration patterns shift and the world recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, the issue of reintegration for returning migrant workers has become more urgent than ever. Governments, international organizations, and grassroots groups are grappling with how to support these returnees, whose remittances have long been a lifeline for their home economies but who now find themselves struggling to rebuild their own lives.

What Awaits Migrant Workers Upon Return?

Returning home is often imagined as a joyful reunion and a return to familiarity. However, for many migrant workers, the reality is far more complex. After years or even decades abroad, they may find their hometowns transformed, their social networks diminished, and their skills undervalued in the local job market.

Ayu Rosita, who spent 15 years as a domestic helper in Saudi Arabia, returned to her village in West Java, Indonesia, only to find it unrecognizable. New businesses had sprung up, the roads were busier, and most of her friends had moved away or passed on. “I felt like a stranger in my own village. I was restless because I was used to working hard every day and now I stay home all day with little to do,” she shared. Her experience is echoed by many returnees who struggle with feelings of isolation, loss, and a lack of purpose.

Similarly, Faye Miranda from the Philippines returned from Kuwait to care for her gravely ill son, only to lose him days after her arrival. The grief, compounded by guilt and the abrupt end to her overseas employment, led to depression and a sense of disconnection from her community.

Psychosocial and Emotional Challenges: More Than Just Homesickness

The emotional toll of reintegration is significant. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), returning migrants often experience a rupture between who they have become during their time abroad and who they are expected to be by those who knew them before. This identity shift can lead to feelings of frustration, shame, and anxiety, especially when returnees are met with suspicion or stigma.

Social exclusion is a major risk. Returnees may be perceived as failures if they come back without significant wealth, or as outsiders if they have adopted new accents, habits, or worldviews. In some cases, as reported in both Indonesia and the Philippines, returnees are even ridiculed for their changed mannerisms or struggle to reconnect with children and spouses after years apart. The absence of a strong support network can exacerbate these feelings, leading to depression and, in severe cases, mental health crises.

Women, in particular, face heightened challenges. An IOM study found that female returnees often struggle more than men to access employment, training, and healthcare, especially if they have experienced abuse or exploitation abroad. The trauma of such experiences can linger long after their return, affecting their ability to reintegrate and rebuild their lives.

Economic Hurdles: From Breadwinners to Job Seekers

One of the most pressing challenges for returning migrant workers is finding sustainable employment. Many left their home countries due to a lack of job opportunities, and upon return, they often find the situation unchanged—or even worse. Age, lack of formal education, and the perception that overseas experience does not translate into valuable skills at home can all be barriers to employment.

For example, Ayu Rosita attempted to start a fish farming business and later a small shop, but faced stiff competition and slim profit margins. Faye Miranda, despite her years of hard work abroad, found it difficult to secure a job in her hometown, with employers preferring younger candidates with formal qualifications. These stories are not unique. A 2019 IOM study found that 31% of Southeast Asian migrant workers had no change in their savings upon return, while 21% saw their savings decrease, and 17% accumulated debt.

In Timor-Leste, research by Flinders University revealed that less than half of returning workers were able to maintain a sense of wellbeing, with many unable to find jobs that matched the skills they acquired abroad. This mismatch often leads to a desire to migrate again, perpetuating a cycle of labor migration and return.

Government and Community Responses: Are They Enough?

Recognizing the scale of the problem, governments in major migrant-sending countries like Indonesia and the Philippines have introduced various reintegration programs. These include cash assistance, soft loans, entrepreneurship training, and upskilling courses. For instance, Indonesia offers low-interest business loans and collaborates with educational institutions to provide training, while the Philippines’ Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA) provides grants and capacity-building seminars.

However, the reach and effectiveness of these programs remain limited. In 2023, only a small fraction of the hundreds of thousands of returning Filipino workers benefited from OWWA’s cash assistance or training programs. Many returnees, especially those who migrated through informal channels or lack proper documentation, are unable to access support. The same is true in Nepal and Egypt, where government programs often exclude undocumented workers, leaving them reliant on family networks or forced to consider re-migration.

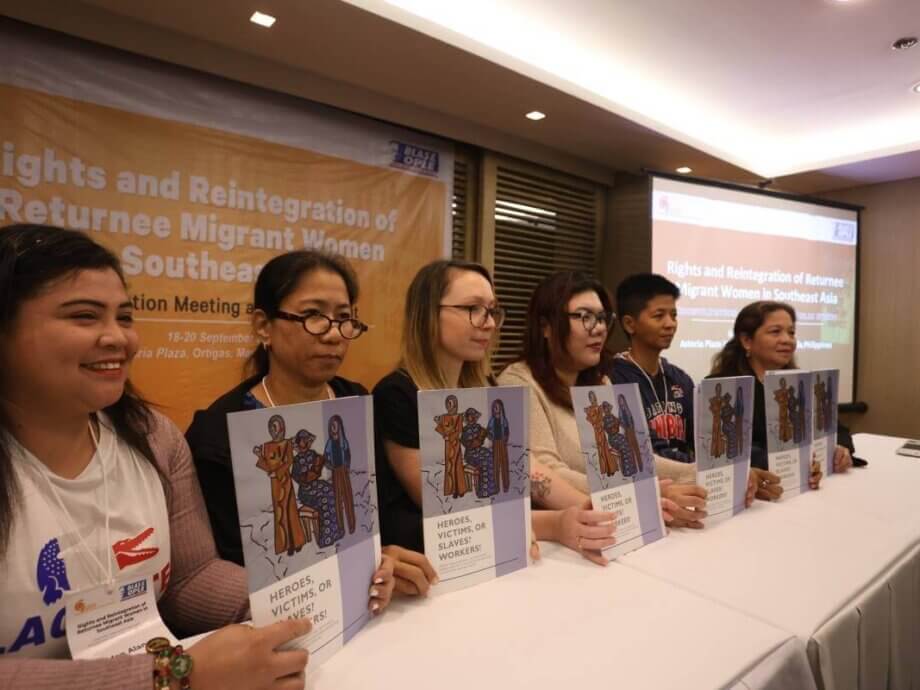

Grassroots and community-based initiatives have emerged to fill some of these gaps. In Indonesia, informal support groups and empowerment workshops have helped returnees rebuild social connections and explore new livelihood opportunities. In the Philippines, organizations like Sandigan provide psychosocial support and a space for returnees to share their experiences and cope with trauma. These efforts, while valuable, are often under-resourced and lack the scale needed to address the broader systemic challenges.

Structural and Policy Barriers: The Need for a Holistic Approach

Experts agree that successful reintegration requires more than individual resilience or piecemeal support. The IOM and International Labour Organization (ILO) emphasize the need for coordinated, multi-level strategies that address economic, social, and psychosocial dimensions. This includes:

- Recognizing and accrediting skills acquired abroad to improve job prospects at home

- Providing accessible mental health and counseling services

- Ensuring financial literacy and entrepreneurship training are tailored to local market realities

- Engaging communities to reduce stigma and foster acceptance of returnees

- Developing robust data systems to match returnees’ skills with available opportunities

Legislative efforts, such as the proposed House Bill 11130 in the Philippines, aim to institutionalize comprehensive reintegration programs, including job fairs, livelihood support, psychosocial counseling, and community engagement. Yet, implementation remains a challenge, often hampered by limited resources, bureaucratic hurdles, and a lack of coordination among agencies.

Gendered and Vulnerable Groups: Who Faces the Greatest Risks?

While all returnees face reintegration challenges, certain groups are particularly vulnerable. Female migrant workers, especially those who have experienced abuse or exploitation, often struggle with trauma, health issues, and social stigma. Domestic workers, whose skills are undervalued in formal job markets, may find it nearly impossible to secure stable employment upon return.

Children and adolescents who return after years abroad may face language barriers, cultural dislocation, and difficulties in school. Families separated by migration often struggle to rebuild relationships, with children sometimes exhibiting behavioral problems or poor academic performance. Marriages can be strained by long absences, and infidelity is not uncommon, further complicating the reintegration process.

Lessons from Around the World: Comparative Perspectives

The challenges faced by returning migrant workers are not unique to Southeast Asia. In Nepal, the COVID-19 pandemic forced hundreds of thousands of workers to return home, many of whom found themselves excluded from government support due to lack of documentation. In Egypt, failed reintegration has led to patterns of circular migration, with workers repeatedly leaving and returning as a livelihood strategy. In Timor-Leste, the lack of formal recognition for skills acquired abroad has left many returnees underemployed and eager to migrate again.

These international examples underscore the importance of comprehensive, inclusive policies that address the full spectrum of returnees’ needs. Without such support, the cycle of migration and return is likely to continue, with all its attendant social and economic costs.

The Broader Picture: Migration, Development, and the Future

Remittances from migrant workers are a major source of income for many countries. In 2023, overseas Filipinos sent home over $40 billion, accounting for nearly 10% of the Philippines’ GDP. Indonesian workers abroad contributed $11 billion, representing 0.8% of their country’s GDP. These funds support families, drive local economies, and, in some cases, help lift entire communities out of poverty.

However, reliance on labor migration as a development strategy has its drawbacks. As Angelo Jimenez, president of the University of the Philippines and a labor rights advocate, points out:

“Remittances from migrant workers have contributed so much to these countries’ economies that some governments spend more time promoting and encouraging people to work overseas than developing their own industries. The most important thing for a country is to provide jobs so that migration becomes only a choice and not a necessity.”

As countries like the Philippines and Indonesia seek to balance the benefits of migration with the need for sustainable development at home, the experiences of returning migrant workers offer valuable lessons. Ensuring that migration is a choice, not a necessity, requires investment in domestic job creation, education, and social protection systems that can support both those who leave and those who return.

In Summary

- Returning migrant workers face significant emotional, social, and economic challenges upon coming home, including isolation, stigma, and limited job opportunities.

- Women and vulnerable groups, such as domestic workers and undocumented migrants, often encounter greater barriers to reintegration.

- Government programs for reintegration exist but often reach only a small fraction of returnees and may not address their actual needs.

- Community-based support groups and grassroots initiatives play a crucial role in providing psychosocial support and fostering social connections.

- Comprehensive, coordinated policies that recognize skills, provide mental health support, and foster economic opportunities are essential for sustainable reintegration.

- Overreliance on labor migration for economic development can undermine domestic job creation and perpetuate cycles of migration and return.

- Ensuring that migration is a choice, not a necessity, requires long-term investment in local economies, education, and social protection systems.