A Breakthrough in Nature Electronics

Chinese researchers have developed a stretchable microelectrode that dynamically adapts to the brain’s natural movements, solving a critical technical barrier that has long hindered the clinical application of invasive brain-computer interfaces. The work, led by Fang Ying at the Chinese Institute for Brain Research Beijing, appeared in the journal Nature Electronics on February 6, 2026. The innovation addresses a fundamental challenge in neurotechnology. While conventional flexible electrodes can bend, they cannot stretch. This limitation causes them to retract from neural tissue when the brain pulsates with each heartbeat or shifts position within the skull. The new electrode architecture uses a spiral design to convert stretching forces into harmless bending motions, allowing the device to move with the brain rather than resisting it. The spiral geometry permits the electrode to extend and compress like a spring, accommodating the brain’s rhythmic motions without transmitting damaging shear forces to delicate neural tissue.

The issue first became visible to Fang’s team during experiments with non-human primates approximately four years ago. In an exclusive interview, she explained that the team observed flexible electrodes carrying a genuine risk of retraction due to brain movement. This observation prompted the research team to explore new structural approaches that would allow electrodes to stretch without applying damaging force to the surrounding tissue.

Why Flexible Is Not Enough

The problem of electrode retraction gained international attention in 2024 when Elon Musk’s Neuralink reported that approximately 85 percent of its 1,024 flexible electrodes had retracted from the first human patient’s brain within weeks of implantation. The brain is not a static organ. It moves roughly 100 micrometers with each cardiac cycle and shifts position with breathing and head motion. Traditional linear electrodes, while bendable, lack the mechanical compliance to accommodate this constant motion. When one end of an electrode is anchored to the skull and the other to the brain tissue, any relative movement creates tension. Conventional designs respond to this tension by pulling away from the tissue, leading to signal loss, inflammatory responses, and the formation of scar tissue around the implant site. This mechanical mismatch has represented one of the most stubborn barriers to long-term invasive BCI stability. The resulting scar tissue, known as glial scarring, insulates the electrode from nearby neurons, progressively degrading signal quality until the device becomes effectively useless.

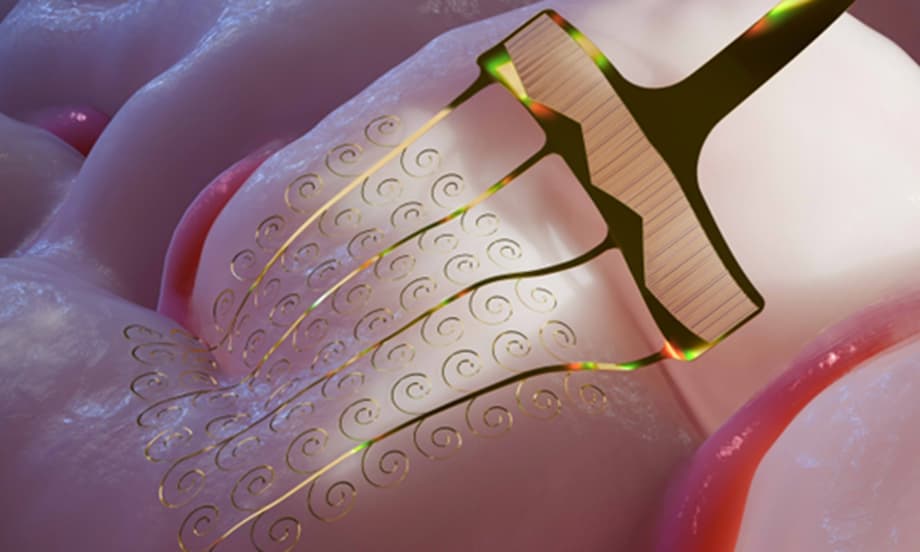

The Spiral Architecture

The solution involves a fundamental rethinking of electrode geometry. Rather than using straight or simply curved wires, the team designed the electrodes as ultrathin spiral structures. The key innovation lies in how the device manages mechanical stress. When the brain moves, the spiral structure converts tensile stretching into low-energy buckling deformations, essentially bending and coiling rather than pulling away. This architectural choice dramatically reduces the force required to accommodate movement. According to Fang, stretching a conventional linear electrode by 100 micrometers requires approximately 4 millinewtons of force. The new stretchable design requires only 37 micronewtons, roughly one-hundredth of the force. This reduction in mechanical stress directly translates to reduced tissue damage and fewer immune responses at the implant site.

The electrodes are fabricated from ultrathin flexible films that combine high-throughput neural signal acquisition with biomechanical compliance. The research team successfully tested a 1,024-channel high-density array in macaque monkeys, demonstrating both large-scale signal acquisition and long-term stability. This scale matches the core specifications of commercial systems while offering superior mechanical integration with living tissue.

From Laboratory to Living Patients

The electrode breakthrough arrives amid a broader acceleration in Chinese invasive BCI development. In March 2025, the Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, collaborating with Huashan Hospital affiliated with Fudan University, launched China’s first-in-human clinical trial of an invasive BCI system. The trial made China the second nation, after the United States, to advance invasive brain-computer interfaces to the clinical stage. The surgical team employed high-precision navigation systems to place the electrodes within the motor cortex with millimeter accuracy, minimizing trauma during the procedure.

The first participant, a man who lost all four limbs in a high-voltage electrical accident 13 years ago, received the implant on March 25, 2025. Within two to three weeks of training, he could control electronic devices using only his thoughts, skillfully operating racing games and chess programs. A second patient, identified as Mr. Zhang, who suffered a high-level spinal cord injury in 2022, has achieved even more notable functionality. After receiving the WRS01 wireless implant in June 2025, he learned to control a smart wheelchair, command robotic dogs, and perform paid remote work verifying products for vending machines. He became the first known BCI trial participant to achieve gainful employment using only neural signals.

It has been more than three years since the incident, and now I can finally work again.

The patient explained his role as an intern sorter controlling a computer cursor with his thoughts. The system processes neural signals, interprets movement intentions, and generates control commands within tens of milliseconds, faster than the blink of an eye.

China’s Expanding BCI Ecosystem

Beyond the academic research setting, commercial development is accelerating rapidly. Zhiran Medical, a company co-founded by Fang Ying, recently secured over 300 million yuan in Series A financing to advance the clinical translation of invasive BCI technology. The company has developed fully implantable wireless systems supporting up to 1,024 channels, with coin-sized processors that reduce power consumption by 75 percent compared to earlier designs. The firm has established clinical-grade manufacturing facilities in Beijing capable of producing the stretchable electrodes at scale.

Other players are entering the market with complementary approaches. StairMed Technology has developed ultra-flexible electrodes measuring one-hundredth the diameter of a human hair, allowing brain cells to barely perceive their presence. The company plans multi-center trials with 30 to 40 participants, targeting market approval by 2028. Meanwhile, Shanghai Brain Tiger Technology has demonstrated 256-channel flexible electrode arrays achieving information transmission rates comparable to Neuralink’s published data.

This commercial activity is supported by national policy. China has included BCI development in recommendations for its upcoming 15th Five-Year Plan. In March 2025, the National Healthcare Security Administration established specific pricing items for invasive BCI implantation and removal, creating the regulatory infrastructure for clinical billing and insurance coverage.

The Global Technology Race

The development places China in direct competition with American firms, particularly Neuralink, in the race to commercialize thought-controlled devices. While the United States maintains advantages in chip integration and system-level products, China has carved out distinct strengths in flexible electrode materials and minimally invasive surgical techniques. The Chinese electrodes feature a cross-sectional area between one-fifth and one-seventh the size of Neuralink’s devices, with flexibility exceeding competing products by over 100 times.

Technical approaches diverge significantly. Neuralink’s fully invasive system requires removing a portion of the skull and implanting rigid or semi-rigid electrode arrays, carrying higher surgical risks. Chinese teams have emphasized minimally invasive techniques using small skull incisions and ultra-flexible probes. Lu Junfeng, a neurosurgeon at Huashan Hospital, explained the difference between BCI approaches using a sports analogy. Non-invasive devices are like microphones outside a stadium, picking up only crowd noise. Semi-invasive devices hang above the field, capturing clearer sound. Invasive devices attach directly to the players, hearing every word with perfect clarity.

The Chinese system also benefits from the nation’s strengths in telecommunications infrastructure. The WRS01 system achieves end-to-end latency under 100 milliseconds by utilizing optimized wireless communication protocols, creating control that feels natural and immediate to users.

Technical Challenges Remain

Despite these advances, significant obstacles persist before invasive BCIs become routine medical treatments. Long-term biocompatibility remains a central concern. While acute tests show minimal immune response, the brain’s reaction to foreign objects over years or decades requires continued observation. Researchers must also solve the challenge of device upgrades. Unlike external electronics, implanted systems cannot be easily replaced without additional surgery.

Ethical and security questions accompany the technical progress. Invasive BCIs create direct pathways into the brain, raising concerns about privacy of neural data and protection against unauthorized access. Medical ethicists stress the need for strict standards regarding identity authentication, information encryption, and protection against misuse of brain data. The technology also requires careful psychological screening, as patients must adapt to machines that interpret their thoughts.

At a Glance

- Chinese researchers published stretchable electrode design in Nature Electronics, solving the retraction problem that caused 85 percent of Neuralink’s first human trial electrodes to fail

- The spiral-shaped electrodes require one-hundredth the stretching force of conventional designs, reducing tissue damage and immune responses

- China launched its first invasive BCI clinical trial in March 2025, becoming the second nation after the US to reach this milestone

- Patients have achieved mind control of computers, wheelchairs, and robotic dogs, with one participant returning to paid remote work

- Multiple Chinese companies including Zhiran Medical and StairMed are advancing toward commercial approval targeted for 2028

- The technology is included in China’s upcoming 15th Five-Year Plan, with specific medical billing codes established for BCI procedures