A New Start for English in Primary Classrooms

Vietnam has approved a major shift in language education. English will become a compulsory subject from grade 1 by 2030 under a national program that runs from 2025 to 2035, with a longer vision to 2045. The change replaces the current rule that makes English compulsory from grade 3. It also extends English exposure to preschools within five years. The aim is not only earlier lessons. The goal is to build an English language environment across schools so students use the language in classes, activities, and daily communication on campus.

- A New Start for English in Primary Classrooms

- What is driving the shift

- How the rollout will work

- Teacher gap and training challenge

- Rural and remote areas, closing the gap

- What will first graders actually learn

- Parents and educators react

- Financing, materials, and technology

- International cooperation and standards

- Risks to watch

- Key Points

The Ministry of Education and Training has set a clear direction. By 2035, all general education students are expected to study English as a second language under the program. The plan includes standards for teaching quality, digital learning, teacher capacity, and the use of English in school life. It matches a broader national push for stronger foreign language skills tied to economic growth and deeper global integration.

The move comes as parents push for earlier access. Many families already pay for out of school lessons to start English at age six or earlier. Making English free in public schools from grade 1 promises to reduce that burden while expanding access to students outside large cities.

What is driving the shift

English is the most widely studied foreign language in Vietnam and has been compulsory from grade 3 through grade 12 for years. It is the language most often used with visitors, foreign employers, and higher education partners. Earlier instruction seeks to capture the advantages of young learners, who pick up sounds and basic communication more naturally than older students. Policymakers also link stronger English skills to workforce competitiveness in trade, tourism, technology, and higher education.

Experience from local pilots has shaped the decision. In Ho Chi Minh City, first grade English has run for more than a decade, with near universal participation. The model focuses on songs, games, simple classroom talk, and friendly routines. Parents say this helps children get comfortable without heavy pressure while teachers keep the pace gentle and encouraging.

How the rollout will work

Authorities will phase in the change over several years. All primary schools must add English from the first grade by 2030, with schools that already have qualified teachers encouraged to start sooner. Preschools will introduce English exposure within five years. Universities and vocational schools are expected to expand teaching, research, and daily use of English to create a bilingual study and work environment on campus.

Timelines and milestones

Education planners will measure progress with system wide targets. By 2030, primary schools nationwide teach English from grade 1. The program expects a growing share of schools to reach defined levels for English use in teaching, communication, and learning environments. Targets include at least 20 percent of schools at Level 1, 5 percent at Level 2, and 2 percent at Level 3 by 2030. By 2045, the shares rise to 50 percent, 20 percent, and 15 percent respectively. Preschools are expected to meet 10 percent at Level 1 by 2030 and half by 2045. In higher education, by 2035 half of universities are expected to meet Level 2 and 35 percent to meet Level 3.

School standards and evaluation

Schools will be assessed at three levels. Reviews cover teacher qualifications, classroom time, curriculum design, digital learning tools, the use of English in school life, and international collaboration. The focus is not only language lessons. It also looks at how often English appears in other subjects, in extracurricular clubs, and in daily routines, such as assemblies or student projects. The idea is to make English a tool for learning, not just a subject for tests.

Teacher gap and training challenge

Making English compulsory from grade 1 will require a larger and better prepared teaching force. Official estimates point to a need for about 12,000 additional English teachers for preschools and 10,000 for primary schools. Education leaders also plan to retrain or upskill a large cohort of existing staff who teach other subjects so they can teach in English. Targets for this group reach at least 200,000 teachers over the coming decade. Separate planning documents put the combined need for new preschool and primary English teachers at roughly 22,000 by 2030.

Vietnam has experience with national standards for language teaching. Since 2008, the system has aligned teacher and learner proficiency with the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. That standard has guided curriculum design, testing, and teacher development. Expanding English from grade 1 will test this system at scale, especially at the primary level where teachers need both language competence and a strong grasp of how young children learn.

Building capacity will mean a mix of pathways. Universities can expand pre service training in primary English education. Provinces can offer scholarships tied to service in public schools, with extra incentives for hard to staff districts. School networks can use team teaching, peer mentoring, and micro credentials that recognize progress in both English and pedagogy for young learners. Digital platforms can help teachers plan lessons, model pronunciation, and build classroom routines that prioritize listening and speaking.

International cooperation will play a role. Education officials have opened talks with partners, including recent meetings with the United Kingdom on skills and teacher training. Collaboration can include joint programs for teacher education, classroom observation exchanges, and high quality resources that match local curricula and age groups.

Rural and remote areas, closing the gap

The policy aims for universal access, yet conditions vary widely across Vietnam. Studies of rural and remote regions point to shortages of qualified teachers, thin budgets for materials and equipment, and slow or uneven execution of national guidelines. In some mountainous districts, primary schools still rely on a single English teacher who rotates across several schools. Teachers report heavy dependence on textbooks, limited time for lesson preparation, and assessments that stress memorization over communication skills.

Bringing English to every first grader will require targeted support for these communities. Provinces can prioritize recruitment and housing for teachers who agree to serve in remote areas. Mobile teacher teams can cover clusters of small schools on a predictable schedule so children receive steady instruction. Equipment plans should include durable speakers, picture cards, and printed readers, not just screens that are hard to maintain. Connectivity is improving, yet many classrooms still need offline solutions. Content that runs on low cost devices and teacher guides for no tech activities can narrow the gap.

Local context matters in multilingual communities. Teachers benefit from training that helps them bridge Vietnamese and local languages while keeping lessons simple and playful. Parent workshops can show families how to support learning through songs, stories, and picture books at home. With the right support, rural schools can move from sporadic exposure to regular English time that children look forward to each week.

What will first graders actually learn

First grade English should look and feel different from secondary school classes. Children at this age are still mastering reading and writing in Vietnamese. Early English lessons work best when they focus on listening and speaking, familiar routines, and meaningful repetition. Songs, chants, role play, simple classroom commands, and story time help children connect sounds with meaning. This builds confidence and prepares them for reading and writing in later grades.

Heavy grammar drills can discourage beginners. A gentle pace allows children to enjoy class without fear of testing. Teachers can use games to practice greetings, colors, numbers, classroom objects, and basic actions. Short tasks with clear successes keep energy high. Visuals, puppets, and total physical response activities turn language into movement and play. Over time, children move from single words to short phrases and simple conversations. Clear goals, such as understanding classroom rules in English or retelling a short story with pictures, help teachers track progress without constant formal tests.

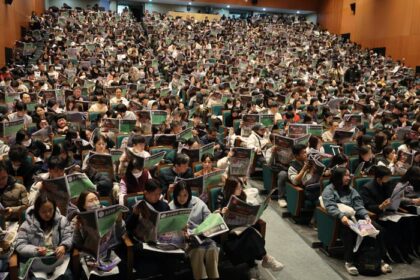

Parents and educators react

Many families welcome the change because it promises earlier access in public schools and a chance to reduce private tutoring costs. Some parents already pay for after school lessons to help children start early. They hope free instruction in school will deliver the same benefits in a more convenient setting.

Van Quy, a father in Hanoi, has been paying each month for private lessons so his daughter can speak with confidence before primary school begins.

“I think this is extremely necessary. Even though I worry a bit about how she will adapt, I completely support it. I would even like to see it start in kindergarten,” he said.

Thu Hue, a mother with a first grader in Hanoi, said school based English would make a real difference for her budget.

“If English becomes mandatory, that means we will save some money. Any savings help, so I am really looking forward to it,” she said.

Teachers see long term benefits when children start early. Teo Thi Thanh Mai, principal of Le Quy Don Primary School in Hanoi, praised the direction.

“Starting English from grade 1 will create a generation trained in foreign languages from an early age,” she said.

In Ho Chi Minh City, where first grade English has been offered widely for years, parents describe a light touch that blends music, games, and simple talk. Thanh Ngan, a mother of three, said the format made life easier for families.

“Learning at school makes it easier for parents, and teachers can guide the children closely,” she said.

Some parents remain cautious about quality, especially if schools struggle to find fluent teachers. Concerns center on classes that rely on vocabulary lists and grammar worksheets, which can turn beginners away from speaking. These families want a design that keeps first grade classes lively, short, and focused on communication.

Financing, materials, and technology

Scaling early English will require steady funding, reliable materials, and smart use of technology. Free lessons in public schools mean provinces must budget for teachers, training, and classroom resources. Materials for young learners should include picture rich textbooks, readers, flashcards, and simple audio that teachers can play in any room. Selection and procurement should align with national standards so schools use age appropriate resources with clear learning goals for each grade.

Digital tools can extend reach when used with care. Learning platforms can give teachers ready made lesson plans, printable activities, and short videos that model actions and simple dialogues. Artificial intelligence can help generate worksheets and track progress on listening and pronunciation, yet it should support, not replace, live interaction in class. Schools with limited connectivity need options that work offline. The best tools are simple, low cost, and easy for teachers to adapt to their own students.

International cooperation and standards

Vietnam has aligned English teaching and learning with international frameworks for more than a decade. Continued alignment with the Common European Framework of Reference helps set expectations for listening, speaking, reading, and writing at each stage. Partnerships with other countries can bring training expertise, accredited programs, and exchange opportunities for educators. Recent talks with education officials in the United Kingdom point to growing cooperation on teacher training and skills.

International support can accelerate progress, yet local adaptation remains essential. Materials and methods must fit Vietnamese classrooms, available resources, and cultural context. Training that blends global best practice with local examples has the greatest chance of success.

Risks to watch

The plan is ambitious. The benefits are compelling, yet success will depend on steady execution. Key risks are manageable if they are addressed early with clear guidance and support.

- Teacher supply and quality, recruiting and retaining enough primary English teachers with strong pedagogy for young learners.

- Uneven access, ensuring rural and remote schools receive resources, training, and support at the same pace as cities.

- Teaching methods, avoiding test heavy, grammar first approaches that dampen motivation in grade 1.

- Materials and equipment, providing reliable, age appropriate resources that do not depend on constant internet access.

- Assessment, tracking communicative progress without over testing young children.

- Budget and governance, aligning national guidance with provincial plans, steady funding, and clear roles for schools and teacher training institutions.

Key Points

- English becomes compulsory from grade 1 by 2030, replacing the current grade 3 start.

- The program runs 2025 to 2035 with a vision to 2045 and seeks to build an English language environment in schools.

- The Ministry targets all general education students studying English as a second language by 2035.

- School evaluation uses three levels tied to teacher capacity, curriculum, digital tools, and everyday use of English.

- By 2030, targets include at least 20 percent of schools at Level 1, 5 percent at Level 2, and 2 percent at Level 3, rising further by 2045.

- Preschools will introduce English exposure within five years, and universities are expected to expand use of English in teaching and research.

- Teacher needs include roughly 12,000 for preschools, 10,000 for primary schools, and large scale upskilling of teachers to teach in English.

- Parents widely support the change, though concerns remain about teacher quality and over reliance on grammar and tests.

- Rural and remote areas will need targeted support, including teacher incentives, mobile teams, and offline learning materials.

- International cooperation, including with the United Kingdom, is part of the plan to build the teaching workforce and resources.