PNG weighs a landmark alliance as China pushes back

Papua New Guinea is at the center of a high stakes security debate after China urged Port Moresby not to sign any defence pact that would limit third country cooperation. The warning came days after a planned mutual defence treaty with Australia, known informally as the Pukpuk treaty, stalled at the final step. Instead of an agreement, the two governments signed a communique confirming the wording of the treaty and promising to complete cabinet processes before a formal signature.

- PNG weighs a landmark alliance as China pushes back

- Inside the Pukpuk treaty

- Why the signing stalled

- China’s message and Papua New Guinea’s balancing act

- Sovereignty concerns inside Papua New Guinea

- What Papua New Guinea’s defence actually needs

- Regional stakes for Australia and the Pacific

- What happens next

- Key Points

The proposed treaty would be the most consequential shift in Australia and Papua New Guinea security ties in decades, pledging mutual defence if either faces an armed attack and laying out deeper military integration. The debate is intense. Papua New Guinea leaders say Australia remains the country’s security partner of choice. Chinese officials caution against any deal that excludes others or targets a third party. Former Papua New Guinea commanders and opposition figures warn about sovereignty and constitutional limits. The result is a careful balancing act for a country that trades heavily with China, relies on Australia for security support, and prefers a posture of friends to all, enemies to none.

Inside the Pukpuk treaty

Officials in both capitals say the treaty text is agreed. While full details are not public, statements from leaders, explanatory briefings and past cooperation show the broad shape. At its core, the agreement recognises that the security of both countries is linked and seeks to turn years of practical collaboration into a formal alliance. It updates a longstanding relationship built through training, joint exercises, and maritime surveillance.

Mutual defence promise

The Pukpuk treaty would state that an armed attack on either country would threaten the peace and security of both. This is a clear mutual defence commitment, similar in concept to Australia’s alliance with the United States under ANZUS. For Papua New Guinea, it would be the first treaty of this kind. For Australia, leaders say it would be the first new alliance in more than 70 years. That legal language matters because it sets expectations for consultation and action at moments of high pressure.

Personnel and interoperability

The agreement envisages integration of forces over time. Papua New Guinea citizens could serve in the Australian Defence Force, and Australians could serve with Papua New Guinea units. Joint training would lift shared standards. Exercises would expand across land, sea, air and cyber domains, improving logistics, communications and planning. Australia is grappling with persistent recruitment shortfalls, while Papua New Guinea sees skills, training and income pathways for young people as a benefit. Policymakers also note the need to plan carefully for returning personnel so gained skills translate into steady employment at home.

Beyond warfighting

Security in the Pacific often means more than preparing for armed conflict. Illegal fishing, transnational crime, cyber attacks, disaster response and humanitarian crises regularly strain limited resources. The treaty sits alongside a broader 2023 security agreement and is expected to streamline cooperation in these areas. Papua New Guinea’s vast maritime zone, rugged terrain and long borders stretch enforcement capacity. A structured framework for maritime patrols, aerial surveillance, engineering, logistics and emergency response would address day to day needs that matter to communities.

Why the signing stalled

The plan had been to sign during Papua New Guinea’s 50th independence celebrations in Port Moresby. The cabinet meeting that would have endorsed the document did not reach a quorum, a procedural snag that leaders said would be resolved. Rather than force a decision, the prime ministers endorsed a communique that locks in the wording and commits both cabinets to complete their reviews.

Australia’s prime minister underscored that the delay was a process issue and expressed confidence about the timeline.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese told reporters the agreement is on track to be signed soon. He said it would be Australia’s first new alliance in over 70 years. He added that work between the governments would continue in coming weeks.

“I am confident the treaty will be signed in coming weeks,” Albanese said, adding that the agreement would lift the partnership to a new level.

Papua New Guinea’s leader reiterated that Canberra remains Port Moresby’s preferred security partner, while insisting the country retains its independence in decision making.

Prime Minister James Marape said Australia is Papua New Guinea’s “security partner of choice,” and that the choice of partners is a sovereign decision.

China’s message and Papua New Guinea’s balancing act

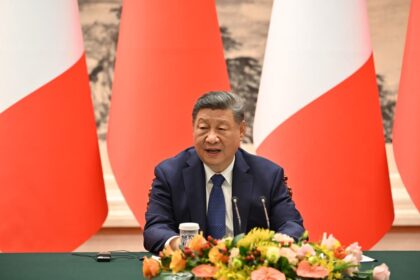

Beijing has made its position clear through an embassy statement in Port Moresby. The message acknowledged Papua New Guinea’s right to sign treaties, while warning against any exclusive arrangement that constrains other partnerships or targets a third party. The language reflects China’s sensitivity to new defence pacts in the Pacific after it reached a security deal with the Solomon Islands in 2022, a move that triggered regional concern.

The Chinese embassy framed the matter in terms of sovereignty and long term interests, urging Papua New Guinea to maintain independence in foreign policy decisions.

The Chinese embassy said any treaty “should not be exclusive, restrict cooperation with third parties, or undermine the legitimate rights and interests of others.”

Port Moresby, mindful of major trade ties with China and deep security links with Australia, is signaling openness to dialogue. The prime minister said the defence minister would brief China and Indonesia on the treaty’s parameters. That outreach aims to reassure neighbors that a bilateral alliance will not shut the door on other cooperation. It also reflects Papua New Guinea’s longstanding preference for nonalignment in great power competition.

Sovereignty concerns inside Papua New Guinea

The treaty has triggered vigorous debate in Port Moresby. Political leaders and former defence chiefs have pressed for caution. They argue that any binding military commitments must sit squarely within the constitution and the country’s principle of friendship with all. Several have warned against any provision that could constrain relationships with other partners or encroach on domestic jurisdiction over foreign forces.

Opposition leader Douglas Tomuriesa urged strong safeguards and review mechanisms so that sovereignty is protected and constitutional authority remains intact. Former commanders Gilbert Toropo and Peter Ilau have said Papua New Guinea should keep freedom of engagement with a range of countries, given overlapping interests across the region. They want clarity on how the treaty would affect cooperation with neighbors and on the terms for visiting forces inside Papua New Guinea.

Retired major general Jerry Singirok has been among the most prominent critics. He warned that merging forces could breach constitutional boundaries and run counter to Papua New Guinea’s preference to be friends to all and enemies to none. He also rejected claims that China is an adversary for Papua New Guinea, arguing the country should avoid taking sides in rivalries among larger powers.

These critiques put a spotlight on Status of Forces Agreements that govern the legal standing of foreign personnel. Papua New Guinea has previously limited Australian deployments to advisory roles to avoid friction with domestic law and courts. Any new framework will need clear rules for privileges, immunities and jurisdiction, which can be politically sensitive.

What Papua New Guinea’s defence actually needs

A prominent Papua New Guinean scholar has questioned whether a mutual defence alliance addresses the most pressing security needs at home. He argued the focus should be on maritime and border enforcement, policing and disaster response, rather than preparing for expeditionary combat. The pitch aligns with concerns that oversized military investments could distort institutions or spill into domestic conflicts if not carefully managed.

Before that argument gained traction in public debate, the scholar laid out a practical shopping list for state capacity.

Michael Kabuni wrote: “What PNG needs are coastguard style capabilities: maritime patrols, satellite monitoring, fisheries enforcement, customs and border policing, engineering units and disaster response teams.”

He cautioned that rapid expansion of military budgets without matching governance and oversight can produce unintended consequences. Fiji’s experience with a well resourced military has often been cited as a warning about the risk of outsized political influence. In Papua New Guinea’s context, community structures and local obligations can complicate control of weapons, raising fears that arms meant for national defence could leak into tribal conflicts. Advocates for the treaty respond that a carefully designed program can channel resources to policing, surveillance and civil defence while training the army to support emergency response.

Regional stakes for Australia and the Pacific

For Canberra, formalising a mutual defence alliance with Papua New Guinea is part of a broader response to accelerated strategic competition in the Pacific. China’s security outreach, police training programs and regular naval presence have reshaped perceptions of risk around Australia and across island states. Regional partners still trade extensively with China, yet they also seek reassurance that no single power will dominate their security choices.

Australia has pursued a series of agreements in the Pacific, some still moving through domestic processes. A planned security partnership with Vanuatu was delayed for internal review, highlighting how island governments weigh access to development financing, including from China, when evaluating new security deals. In parallel, Australia is implementing the AUKUS plan with the United Kingdom and the United States for nuclear powered submarines, a complex undertaking now under review by American authorities. All of this points to a dynamic environment where timing and diplomatic tone are crucial.

Analysts argue that a Papua New Guinea treaty could deliver concrete benefits if it builds capacity where it is most needed and avoids perceptions of overreach. Priorities include joint maritime patrols, reliable logistics, interoperable communications, cyber defence, and transparent consultation on activities with third countries. Clear public communication would help address domestic sensitivities in Port Moresby and reassure other Pacific Islands Forum members that the arrangement supports regional stability rather than exclusion.

There are economic and social dimensions too. Skills gained through service and training could flow back into civilian fields, from engineering to emergency management. This potential will only be realised if job opportunities exist for returning personnel. Long term sustainability depends on budget discipline, robust oversight, and collaboration between defence and police forces so that capacity lifts across the security sector, not just in the military.

What happens next

Cabinet reviews in both countries must now run their course. Papua New Guinea’s government has indicated the treaty will go to parliament and can be amended later if needed. The defence minister plans consultations with China and Indonesia to explain the document and reduce the chance of misunderstanding. If cabinet endorsements proceed smoothly, leaders say they will sign the treaty soon after.

China, which is hosting a security forum in Beijing attended by military officials from many countries, has not publicly indicated whether it will press the issue beyond the embassy statement. Papua New Guinea is expected to keep engaging all partners, consistent with its trade ties and development priorities. Australia will keep presenting the treaty as a Pacific family arrangement, focused on mutual security and respect for sovereignty.

The coming weeks will determine whether the Pukpuk treaty becomes a headline alliance for the Pacific or remains a communique that falls short. The balance between deterrence, practical cooperation and political sensitivity will shape how this agreement lands at home in Papua New Guinea and across the region.

Key Points

- China urged Papua New Guinea not to sign an exclusive defence pact that restricts third party cooperation.

- Australia and Papua New Guinea signed a communique after a planned mutual defence treaty was delayed by a cabinet quorum issue.

- The proposed Pukpuk treaty includes a mutual defence clause, deeper integration and service opportunities across both forces.

- Papua New Guinea’s leaders say Australia remains the security partner of choice, while promising to safeguard sovereignty.

- Former Papua New Guinea commanders and opposition figures want constitutional safeguards and clarity on legal status for foreign troops.

- Scholars argue PNG’s priority needs are maritime patrols, policing, border control and disaster response.

- The delay follows another setback for Australia’s Pacific outreach after a Vanuatu review of a security partnership.

- Cabinet processes in both countries are expected to conclude in coming weeks, with leaders signaling confidence the treaty will be signed.