The Ancient Faces of Keeladi: A Scientific Breakthrough

In a modest laboratory at Madurai Kamaraj University in Tamil Nadu, India, a team of researchers recently achieved a remarkable feat: they digitally reconstructed the faces of two men who lived 2,500 years ago. These men, whose skulls were unearthed from the Kondagai burial site near Keeladi, have become the new faces of a civilization that is rewriting the history of ancient India. The project, a collaboration between Indian scientists and the Face Lab at Liverpool John Moores University in the UK, combines cutting-edge forensic technology, advanced DNA analysis, and a deep dive into the region’s archaeological record.

- The Ancient Faces of Keeladi: A Scientific Breakthrough

- What Makes Keeladi Special?

- From Skulls to Faces: The Science of Facial Reconstruction

- What Do the DNA and Faces Tell Us About Ancient India?

- Political and Cultural Impact: More Than Just Science

- The Broader Significance: Connecting Past and Present

- What’s Next for Keeladi and Ancient DNA Research?

- In Summary

The Keeladi site, located near Madurai, has emerged as one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in South Asia in recent decades. Its findings challenge long-held assumptions about where and when urban civilization flourished in the Indian subcontinent. The facial reconstructions, unveiled in June 2025, are not just scientific curiosities—they are powerful symbols of identity, heritage, and the enduring diversity of India’s people.

What Makes Keeladi Special?

Keeladi is not just another archaeological dig. Since its discovery, the site has yielded evidence of a sophisticated urban settlement dating back to at least the 6th century BCE. This predates many classical South Indian kingdoms and rivals the famed Indus Valley Civilization of the north. Archaeologists have uncovered brick houses, intricate pottery, beads, tools, and more than 50 large burial urns containing human remains and grave goods.

What sets Keeladi apart is the picture it paints of a literate, skilled, and cosmopolitan society. Inscriptions on pottery suggest the use of a script, while the variety of artifacts points to active trade and cultural exchange. The people of Keeladi lived in brick houses, practiced agriculture, reared cattle, and consumed rice, millets, and dates. They buried their dead with daily necessities, indicating complex rituals and beliefs about the afterlife.

These discoveries have sparked intense debates among historians, politicians, and the public. The narrative that urbanization and advanced civilization were confined to northern India has been upended, and the antiquity of Tamil culture has been thrust into the spotlight.

From Skulls to Faces: The Science of Facial Reconstruction

The journey from ancient skulls to lifelike faces is a blend of science, technology, and a touch of art. The two male skulls, excavated from Kondagai, were selected for their relatively well-preserved condition. However, both were missing their lower jaws, a common challenge in ancient skeletal remains.

Researchers began by carefully cleaning the skulls and extracting tiny samples of tooth enamel for DNA analysis. The skulls were then scanned using high-resolution CT technology, creating detailed 3D digital models. These models were sent to the Face Lab at Liverpool John Moores University, renowned for its expertise in forensic facial reconstruction.

Professor Caroline Wilkinson, director of the Face Lab, explained the process: the team used computer software to digitally sculpt muscles, fat, and skin onto the 3D skull models, following anatomical standards derived from clinical studies of living people. Where the lower jaw was missing, orthodontic and anthropometric data from modern South Indian populations were used to estimate its shape and size. Tissue depth at various points on the face was also estimated using data from contemporary South Indians.

Adding Color: A Controversial Step

One of the most challenging—and controversial—steps was assigning skin, eye, and hair color to the reconstructions. Since ancient DNA from the region is often too degraded to yield precise pigmentation markers, the team relied on photographic databases and the appearance of modern Tamil Nadu residents. This decision, while standard in forensic reconstructions, sparked lively debates on social media and in academic circles about race, identity, and the politics of representation.

Professor G Kumaresan, head of genetics at Madurai Kamaraj University, emphasized, “The portraits show a more complex and inclusive message, highlighting India’s diversity as seen in DNA.”

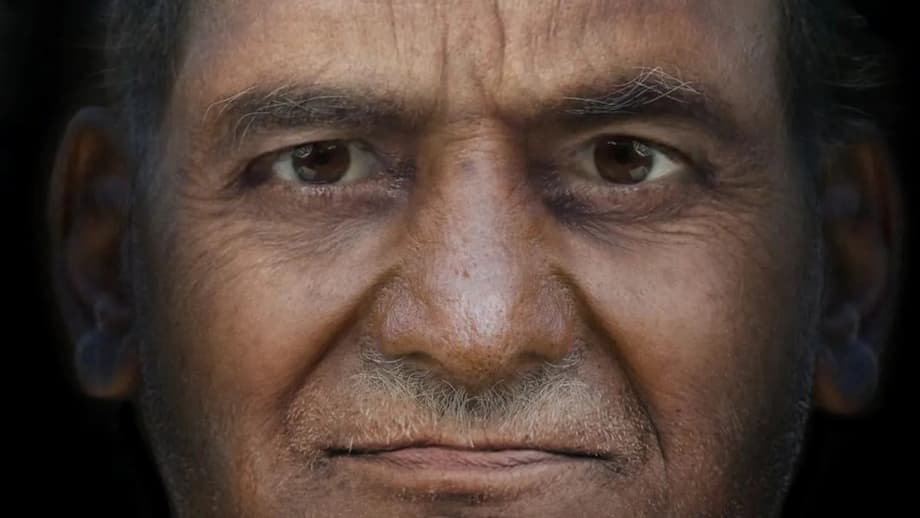

The result is two striking digital portraits: men with predominantly South Indian features, but with subtle traces of West Eurasian (Iranian) hunter-gatherer and Austro-Asiatic ancestry. These faces, for the first time, put a human visage to the people who built and inhabited Keeladi.

What Do the DNA and Faces Tell Us About Ancient India?

The facial reconstructions are more than just visualizations—they are windows into the genetic and cultural history of the region. DNA extracted from the bones and burial urns is being analyzed in collaboration with Harvard University’s David Reich Lab, one of the world’s leading centers for ancient DNA research.

Preliminary results suggest that the Keeladi people were primarily descended from Ancient Ancestral South Indians, believed to be among the earliest inhabitants of the subcontinent. However, the presence of genetic markers from Middle Eastern Eurasian and Austro-Asiatic populations points to ancient migrations and mixing. This supports the idea that South India was not isolated, but part of a broader web of human movement and interaction across Asia.

Such findings challenge simplistic narratives about the origins of Indian civilization. The old dichotomy of Aryan (north) versus Dravidian (south) is giving way to a more nuanced understanding of continuous migration, admixture, and cultural exchange.

Challenges in Ancient DNA Research

Extracting usable DNA from 2,500-year-old remains in a hot, humid climate is notoriously difficult. The DNA degrades rapidly, and contamination is a constant risk. Researchers at Madurai Kamaraj University are working to build a gene library from the Keeladi samples, which could eventually allow for detailed comparisons with both ancient and modern populations across India and beyond.

Professor Kumaresan noted, “The biggest challenge is extracting enough DNA from degraded skeletons to create a gene library, but we hope ancient DNA libraries will reveal new insights about life in the past.”

Despite these hurdles, the integration of facial reconstruction and genetic data is providing unprecedented insights into the ancestry, health, and lifestyles of the people who lived in Keeladi during the Sangam period—a time celebrated in Tamil literature for its poetry, trade, and cultural achievements.

Political and Cultural Impact: More Than Just Science

The Keeladi discoveries have resonated far beyond the academic world. In Tamil Nadu, they have become a source of pride and a rallying point for those seeking to assert the antiquity and uniqueness of Tamil culture. Chief Minister M.K. Stalin and Finance Minister Thangam Thennarasu have both cited the findings as scientific validation of the way of life described in Sangam literature, a body of ancient Tamil poetry and prose.

Chief Minister Stalin declared, “The way of life detailed in Sangam literature is now scientifically validated through the findings at Keeladi.”

The research has also become entangled in political debates. The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) government in Tamil Nadu has accused the central government, led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), of trying to suppress or downplay the significance of the Keeladi findings. Disputes over the dating and interpretation of the site led to the transfer of key archaeologists and calls for the release of official excavation reports.

Despite the controversies, the scientific evidence from Keeladi continues to challenge established narratives and inspire new questions about the origins and development of civilization in South India.

The Broader Significance: Connecting Past and Present

Why does it matter what people looked like 2,500 years ago? For many, seeing the faces of ancient Keeladi makes history tangible and personal. As Professor Caroline Wilkinson explained, facial depictions help people connect with ancient remains as individuals rather than as anonymous artifacts.

The reconstructions also highlight the deep diversity of India’s population, both past and present. The genetic and cultural mosaic revealed at Keeladi is a reminder that migration, mixing, and adaptation have always been part of the human story. The findings encourage a more inclusive and scientifically grounded understanding of heritage, identity, and belonging.

Moreover, the Keeladi project demonstrates the power of international collaboration in science. By combining local expertise in archaeology and genetics with advanced forensic technology from the UK, researchers have set a new standard for interdisciplinary research in South Asia.

What’s Next for Keeladi and Ancient DNA Research?

The work at Keeladi is far from over. Ongoing excavations continue to yield new artifacts, and the analysis of DNA from both human and animal remains promises to shed further light on the region’s ancient economy, diet, and social structure. Researchers hope to build a comprehensive gene library that will allow for detailed studies of migration, health, and adaptation over millennia.

The facial reconstructions are just the beginning. As technology advances and more samples are analyzed, it may become possible to reconstruct entire communities, trace family lineages, and map the spread of ideas and innovations across ancient India.

In Summary

- Researchers in Tamil Nadu, India, have digitally reconstructed the faces of two men who lived 2,500 years ago at the Keeladi archaeological site, using advanced forensic and genetic techniques.

- The Keeladi site reveals evidence of a sophisticated urban civilization in southern India dating back to at least the 6th century BCE, challenging traditional narratives about Indian history.

- Facial reconstructions were created through a collaboration between Madurai Kamaraj University and Liverpool John Moores University, using CT scans, digital sculpting, and anthropometric data.

- DNA analysis shows the Keeladi people were primarily of Ancient Ancestral South Indian descent, with traces of West Eurasian and Austro-Asiatic ancestry, indicating ancient migration and mixing.

- The findings have sparked debates about identity, heritage, and the politics of history in India, while also providing a more inclusive and scientifically grounded understanding of the region’s past.

- Ongoing research aims to build a gene library and further unravel the mysteries of ancient South Indian civilization.