A Power Source Built to Outlast Civilization

Imagine a device that never needs charging. Not once during your lifetime. Not during your children’s lifetimes, or your grandchildren’s, or even your great-grandchildren’s. This vision moved from science fiction to laboratory reality in December 2024, when researchers at the University of Bristol and the UK Atomic Energy Authority unveiled a prototype that challenges everything we assume about energy storage.

The carbon-14 diamond battery generates electricity through radioactive decay with a half-life of 5,700 years. This means the device retains half its original power output after nearly six millennia, long enough to bridge the gap between ancient civilizations and modern technology. Unlike lithium-ion batteries that degrade within years, or even solar panels that require sunlight, this power source operates continuously, sealed within the hardest known natural substance on Earth.

Professor Tom Scott, Professor in Materials at the University of Bristol, leads the team behind this innovation. His research group has spent years developing methods to transform radioactive materials into useful energy sources, culminating in this proof-of-concept device that could reshape how we think about power in inaccessible environments. The announcement represents a significant milestone in nuclear materials research, demonstrating that waste products from fission reactors can become assets rather than liabilities.

The battery’s lifespan defies conventional understanding of energy storage. While modern rechargeable batteries typically last between 500 and 1,000 charge cycles before significant degradation, this diamond-based device would still deliver useful power when historical records from today have faded into archaeological curiosities. The underlying physics of carbon-14 decay provides a clockwork-like reliability that chemical batteries cannot match.

This stability makes the technology particularly valuable for applications where failure is not an option and maintenance is impossible. The prototype represents not just an incremental improvement in battery chemistry, but a fundamental reimagining of how we might power devices across timescales measured in centuries rather than hours.

How Radioactive Decay Becomes Electricity

To understand how this battery works, consider the principles behind solar panels. Traditional photovoltaic cells capture energy from light particles called photons and convert them into electricity. The diamond battery operates on a similar principle called beta-voltaics, but instead of harvesting sunlight, it captures fast-moving electrons released by decaying carbon-14 atoms.

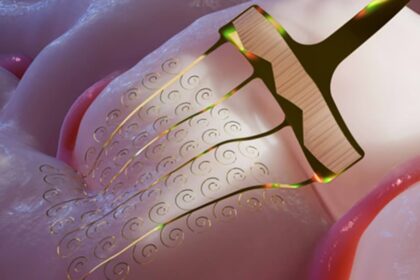

Carbon-14 is a radioactive isotope famous for archaeology, where scientists use its predictable decay rate to date ancient organic materials. The isotope emits short-range beta radiation as it decays, releasing high-energy electrons. In the diamond battery, carbon-14 is embedded within synthetically grown diamond layers. As the isotope decays, it emits beta particles that the diamond’s semiconductor properties convert into electrical current.

The diamond structure serves a dual purpose: it generates power while acting as an impenetrable radiation shield. Because carbon-14 emits only short-range radiation, the diamond casing absorbs all potentially harmful emissions internally. No radiation escapes the device during normal operation, making it safe for medical implants and consumer applications.

Sarah Clark, Director of Tritium Fuel Cycle at UKAEA, explained the safety mechanism behind the technology.

“Diamond batteries offer a safe, sustainable way to provide continuous microwatt levels of power. They are an emerging technology that use a manufactured diamond to safely encase small amounts of carbon-14.”

The prototype batteries measure approximately 10 millimeters by 10 millimeters with a thickness of up to 0.5 millimeters. This compact form factor delivers continuous microwatt-level power, sufficient for low-energy devices but far below the requirements of smartphones or electric vehicles.

Transforming Nuclear Waste Into Energy

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of this technology involves its source material. The carbon-14 used in these batteries comes from graphite blocks removed from nuclear fission reactors, material that would otherwise require expensive, long-term storage as radioactive waste. The United Kingdom alone holds approximately 95,000 tonnes of these graphite blocks, presenting both a storage challenge and an untapped resource.

By extracting carbon-14 from reactor graphite, scientists simultaneously reduce nuclear waste volumes while creating a valuable energy asset. The process involves placing the radioactive material inside synthetic diamond grown through plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Engineers at UKAEA’s Culham Campus built a specialized plasma deposition rig to create these diamond layers with precision, safely locking the radioactive material in place while maximizing energy capture.

This manufacturing technique draws directly from fusion energy research. UKAEA’s expertise in handling radioactive materials, plasma deposition, and specialized semiconductor manufacturing, originally developed for tokamak reactors, translated into the diamond battery project. The collaboration demonstrates how investments in fundamental physics research yield unexpected practical applications.

Professor Neil Fox, Professor of Materials for Energy at the University of Bristol, emphasized the protective qualities of the diamond casing.

“Diamond is the hardest substance known to man; there is literally nothing we could use that could offer more protection.”

When the battery eventually reaches the end of its functional life, it can be returned to manufacturers for controlled recycling or disposal. The carbon-14 remains safely encapsulated throughout the entire lifecycle, addressing both energy needs and environmental concerns. One gram of carbon-14 can deliver 15 joules of electricity daily, outlasting conventional batteries by centuries.

Applications Where Longevity Trumps Power

The diamond battery delivers microwatt-level power, far below what smartphones or electric vehicles require. However, this limitation becomes an advantage in specific contexts where longevity and reliability matter more than raw output. The technology excels in environments where battery replacement is dangerous, expensive, or impossible.

Medical implants represent one of the most promising frontiers. Current pacemakers, hearing aids, and ocular devices rely on traditional batteries requiring surgical replacement every five to ten years. Each replacement procedure carries risks of infection, complications, and recovery time. A diamond battery could power these devices for a patient’s entire lifetime, eliminating repeated operations and reducing healthcare costs. For patients in remote regions with limited access to medical facilities, this longevity could prove life-changing.

Space exploration offers another natural fit. Deep space probes and satellites eventually lose contact when solar panels no longer capture sufficient sunlight or conventional batteries deplete. Voyager 1, the farthest human-made object from Earth, relies on traditional nuclear batteries with limited lifespans. A carbon-14 power source could maintain instruments and communication systems for decades or centuries, enabling missions that extend far beyond current technological limits.

Radio frequency tags on spacecraft or payloads could remain trackable for thousands of years, reducing operational costs while extending mission lifespans. The battery operates effectively in extreme temperatures ranging from minus 60 degrees Celsius to plus 120 degrees Celsius without self-discharge, making it ideal for harsh environments.

Remote terrestrial applications include Arctic monitoring stations, undersea sensors for oil and gas infrastructure, and security devices in inaccessible locations. Any system requiring decades of unattended operation becomes a candidate for this technology. Active radio frequency tags could identify and track devices either on Earth or in space for decades at a time, reducing costs and extending operational lifespan.

The Global Race for Atomic Batteries

While Bristol and UKAEA captured headlines with the first carbon-14 prototype, they are not alone in pursuing nuclear batteries. The technology has sparked international competition, with research teams across China, the United States, and Europe racing to commercialize similar devices using different radioactive isotopes.

Beijing Betavolt New Energy Technology in China announced a competing design using nickel-63 rather than carbon-14. Their BV100 battery, revealed in early 2024, measures 15 millimeters by 15 millimeters by 5 millimeters and generates 100 microwatts at 3 volts. While this nickel-63 approach offers a 50-year lifespan, significantly shorter than carbon-14, Betavolt plans to launch a one-watt version later this year that could power consumer electronics through series connections.

California-based Infinity Power also entered the race in 2024, developing a nickel-63 coin cell similar to Betavolt’s approach. Meanwhile, researchers at Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology in South Korea have experimented with betavoltaic cells using various radioisotopes including carbon and hydrogen isotopes.

The Bristol team maintains a distinct advantage in longevity for specific applications. While nickel-63 batteries offer decades of service suitable for consumer electronics, carbon-14’s 5,700-year half-life provides a fundamentally different value proposition for ultra-long-duration applications where maintenance is impossible. Professor Scott established Arkenlight, a commercial venture, to develop industrial partnerships and evaluate market opportunities for the carbon-14 technology.

China’s approach focuses on near-term commercialization for aerospace, artificial intelligence equipment, and micro-robots, while the UK team emphasizes medical devices and deep space applications requiring extreme longevity. Both approaches share the common goal of eliminating battery maintenance and replacement in critical systems.

Challenges on the Path to Market

Significant hurdles remain before diamond batteries appear in medical devices or spacecraft. The gaseous feedstock for creating pure carbon-14 diamond costs approximately $46,000 per liter, making scaling an economic challenge. Manufacturing requires specialized static-flow chemical vapor deposition reactors installed in active handling facilities, limiting production capacity.

Regulatory approval presents another complex barrier. While the self-contained nature of the diamond casing simplifies safety certification compared to other nuclear technologies, any device containing radioactive material requires extensive testing and oversight. Medical applications face particularly stringent requirements to ensure patient safety over decades of implantation.

Public perception also influences adoption prospects. Despite the technical safety of encapsulated carbon-14, the term “radioactive” carries stigma that may hinder acceptance in consumer markets. Transparent communication about the containment mechanisms and radiation safety will prove essential for widespread adoption.

Professor Scott remains optimistic about overcoming these challenges through continued research. He outlined the development timeline for the coming decade.

“Our micropower technology can support a whole range of important applications from space technologies and security devices through to medical implants. We’re excited to be able to explore all of these possibilities, working with partners in industry and research, over the next few years. We want to use this technology for advancing the human race.”

The decade ahead focuses on upscaling production and improving power performance. Success in scaling manufacturing could reduce costs and enable broader applications beyond specialized medical and aerospace sectors.

Key Points

- Researchers at the University of Bristol and UK Atomic Energy Authority created the world’s first carbon-14 diamond battery in December 2024

- The battery uses radioactive decay of carbon-14 with a 5,700-year half-life, delivering continuous microwatt power for millennia

- Carbon-14 is extracted from nuclear reactor graphite blocks, repurposing radioactive waste into a sealed energy source

- Synthetic diamond acts as both semiconductor and radiation shield, absorbing all emitted particles while generating electricity

- Applications include medical implants (pacemakers, hearing aids), deep space probes, remote sensors, and RF tracking tags

- Competing technologies from China (Betavolt) and the US use nickel-63 with shorter lifespans but nearer-term commercialization

- Commercial rollout requires scaling manufacturing processes and regulatory approval, with production costs currently at $46,000 per liter of feedstock gas