A rare crackdown meets a sprawling fraud industry

China has delivered some of its harshest criminal sentences in years against leaders of Chinese-run scam syndicates based in Myanmar. Courts handed death sentences and long prison terms to members of powerful Kokang families at the center of a vast online fraud economy. The cases are the public face of a sweeping campaign to dismantle cross border cyber scam operations that have trapped thousands of people and stolen billions of dollars from victims in China and around the world.

- A rare crackdown meets a sprawling fraud industry

- How power clans turned Laukkaing into a scam capital

- Death sentences and long prison terms in Chinese courts

- Beijing’s cross border campaign and regional cooperation

- Scam bosses relocate and rebuild away from the spotlight

- Trafficking victims and the methods used by the scams

- How technology and money keep the fraud alive

- What is showing results and what remains difficult

- What to Know

The crackdown zeroes in on compounds that flourished in Myanmar’s borderlands, especially around the town of Laukkaing in the Kokang region. There, mafia style clans grew rich on casinos, prostitution and telecom fraud. Workers were lured by high pay job offers, then confined and forced to run scripted scams. Beijing’s action has humbled once untouchable figures, yet the industry remains agile. Operators shift locations, tap militia protection and rebuild out of reach of most police forces.

How power clans turned Laukkaing into a scam capital

Kokang is a Chinese speaking enclave on Myanmar’s frontier with China. In the early 2000s, clans connected to local militias and power brokers rose after the military sidelined a warlord. The Bai, Ming, Wei and Liu families became the dominant force in Laukkaing, cutting deals with authorities and commanding their own fighters.

They first built casinos and red light districts that drew gamblers from across the region. The next phase was online fraud. Trained teams recruited and coerced workers to run social media romance schemes, fake investment pitches and illegal online gambling targeted at people in China and beyond.

From casinos to cyber fraud

As China’s economy slowed and youth unemployment rose, recruiters dangled tech or customer service jobs in Southeast Asia. Many Chinese traveled willingly, only to find themselves locked inside guarded compounds. Others were trafficked across borders. Victims were ordered to build trust with targets by chatting on messaging apps, then steer them to deposit money into sham platforms. In industry slang, these are known as pig butchering scams, where criminals fatten a target with small gains before wiping out their funds.

Compounds, militias and brutality

Inside the compounds, violence maintained discipline. Workers described beatings, electric shocks and starvation for missing quotas. A Chinese court found that one clan built 41 compounds to house casinos and cyber fraud, generating more than 29 billion yuan in proceeds. The same network was tied to the deaths of six Chinese citizens, the suicide of one more person and many injuries. The clans controlled their own militias and guarded gates, which made escape dangerous and kept local authorities at bay.

Death sentences and long prison terms in Chinese courts

The heaviest blows landed in courtrooms in the Chinese cities of Shenzhen and Wenzhou. Judges there convicted senior figures from two Kokang families of fraud, homicide, injury, illegal detention and other crimes tied to the Myanmar compounds. The sentences were framed as a warning to syndicates that prey on Chinese citizens.

The Bai family cases in Shenzhen

In Shenzhen, five men were sentenced to death. They include Bai Suocheng, a longtime Kokang power broker, and his son, Bai Yingcang, along with Yang Liqiang, Hu Xiaojiang and Chen Guangyi. Two more defendants received a death sentence suspended for two years, a penalty that can later be commuted. Five others were given life in prison, and nine people received prison terms from three to 20 years. The court concluded that the network had created dozens of compounds for casino and cyber fraud, and it highlighted shocking abuse inside those facilities. It also found that Bai Yingcang conspired to traffic and manufacture 11 tonnes of methamphetamine, showing how the fraud economy overlaps with other criminal trades.

The Ming family verdicts in Wenzhou

In Wenzhou, another court sentenced 11 members and associates of the Ming clan to death, with five more receiving death sentences suspended for two years. A further 12 defendants were jailed for periods ranging from five to 24 years. Judges said the group operated compounds protected by armed men and used violence to control workers. The court cited multiple killings, including people who tried to flee. The clan had long been linked to a notorious site known as Crouching Tiger Villa and, at its peak, employed as many as 10,000 people in scams, gambling, drug trafficking and organized prostitution. The family patriarch, Ming Xuechang, died while in custody, according to officials.

Chinese authorities say these verdicts are meant to send a clear signal that crimes against citizens will be punished wherever they occur.

Beijing’s cross border campaign and regional cooperation

China has paired courtroom penalties with a wider push along its southern frontier. Police issued wanted notices with rewards for clan leaders, and authorities pressed Myanmar to hand over suspects. More than 53,000 Chinese suspects linked to northern Myanmar compounds have been returned to China, according to officials. Flights have carried groups of repatriated citizens, with the first planes bringing around 600 people home from border hubs.

The campaign reached beyond Kokang to the Thailand Myanmar border. Chinese, Thai and Myanmar agencies staged joint actions around notorious business estates near Myawaddy, which led to the release of thousands of workers. Officials said more than 7,000 people were freed in one wave, and subsequent operations pushed the total higher. Authorities described the mid 2020s as a period of intensive operations. They also rolled out a multinational program, known in Chinese as Jingyao, with Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam. Officials said the first phase produced more than 70,000 arrests across the region and rescued 160 victims, many of them taken from northern Myanmar.

Pressure on Myanmar and joint police operations

Senior Chinese security officials met counterparts in Bangkok to coordinate repatriations and border controls. In China, the Ministry of Public Security publicly vowed to rescue trafficked people and crack down on compound bosses. Beijing also offered recognition to Myanmar officials for cooperation. At the same time, Chinese diplomats urged Southeast Asian governments to take decisive action against online gambling and telecom fraud that target citizens of many countries.

Why the scams exploded

Myanmar’s civil war after the 2021 coup created space for armed groups and criminal investors to flourish. Border regions are fragmented and law enforcement is weak. Local militias profit from protection fees, land concessions and kickbacks. On the demand side, large numbers of job seekers in China and across Asia were drawn by promises of high pay. Digital payments and offshore platforms allowed money to move quickly, which made fraud easier to scale.

Scam bosses relocate and rebuild away from the spotlight

Criminal networks responded to the pressure by moving. When armed groups and Chinese pressure disrupted operations in Kokang in late 2023, many syndicates shifted south to Myawaddy and the frontier estates of KK Park and Shwe Kokko. Raids and expulsions then pushed leaders and managers across a patchwork of towns and militia zones, or deeper inside Myanmar.

Security sources and civil society groups in Myanmar describe a second wave of relocation to southern and eastern Shan State and to major cities. Some operators crossed into Thailand. Others stayed in Myanmar and rebuilt. Reports from the ground mention equipment being moved out of shuttered zones while new offices open elsewhere. Local border militias such as the Karen Border Guard Force and the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army have been identified by governments as facilitators or protectors of some hubs. The BGF has rejected accusations of involvement in trafficking and says it has cooperated in rescues.

From KK Park to deeper Shan State

New hot spots have emerged beyond the border strip. Townships such as Kunhing, Mongpan, Mong Hsu, Mongyai, Laihka, Tangyan, Namhsan, Mongnawng and Mongping in Shan State have seen an influx of operators and recruits. Travelers describe checkpoints passed with bribes, as well as villages renting homes and selling food to the newcomers. The industry has become part of the local economy in some places, which makes enforcement harder.

Trafficking victims and the methods used by the scams

Stories from survivors illustrate the human cost. People from across Asia and Africa have been lured by recruiters, tricked at airports or sold across borders to guarded compounds. Many were forced to work long shifts on computers and phones, with supervisors demanding daily revenue targets. Punishments for missing quotas included beatings and electric shocks. Families back home often received ransom demands from intermediaries who claimed they could buy a way out.

The fraud follows playbooks. Romance investment schemes remain the mainstay. Victims meet a friendly person online, then are introduced to a trading app that shows early gains. Later, the platform blocks withdrawals. Other teams run fake brokerage desks, phishing attacks and business email compromises that imitate company executives. Workers in the compounds follow detailed scripts and adopt false personas to win trust, then funnel money into wallets controlled by the syndicates.

China’s top diplomat has pressed for a regional response to protect citizens and stop the scams. At a meeting with Southeast Asian envoys, Foreign Minister Wang Yi urged neighbors to take firm steps against online gambling and telecom fraud along the Thailand Myanmar border and beyond.

“We urge regional partners to take decisive action against online gambling and telecom fraud that endanger our citizens.”

Investigators have also tried to speak directly to the public to deter would be scammers who target people inside China. During one briefing, a senior Chinese investigator summarized the purpose of the campaign in stark terms.

“Anyone who commits these crimes against Chinese people will pay the price.”

How technology and money keep the fraud alive

Technology has made the fraud resilient. When authorities cut power, internet or fuel, operators switch to solar panels and satellite links. In parts of Myanmar, Starlink terminals provide high speed connections even in remote valleys. The service is not licensed in Myanmar, yet dishes are common around the Thailand Myanmar frontier. United States agencies have warned the provider about misuse, and lawmakers have asked questions about how equipment reached restricted areas.

Money moves through a mix of traditional bank transfers, crypto tokens and a network of launderers. Analysts tracking flows in Southeast Asia say crime groups have embraced stablecoins, mixers and chains of mule accounts to move funds faster and hide their tracks. Groups also test artificial intelligence to craft convincing messages and scale up outreach. Police forces in many countries say the losses run into the tens of billions of dollars each year. In the United States alone, losses to investment and romance fraud tied to these networks have been estimated in the range of 10 billion dollars a year.

What is showing results and what remains difficult

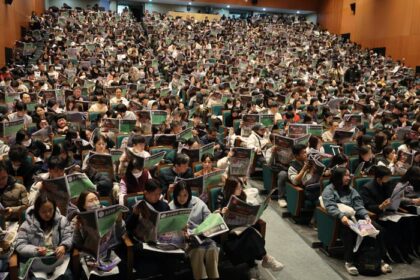

Arrests of clan leaders, death sentences and transfers of suspects from northern Myanmar show that coordinated pressure can bite. Cutting utilities and policing the border have helped free thousands of people. Joint operations and chartered flights have brought Chinese nationals home. Public warnings, including a hit movie about a young couple trapped in a Southeast Asian scam park, have reduced risky travel for some would be job seekers.

The hard part is persistence. Crime bosses shift sites, co opt local armed groups and bribe officials. Compounds spring up deeper inside conflict zones, far from reporters and foreign consulates. New victims arrive from countries with fewer resources to intervene. Without sustained cooperation across police forces, financial regulators, tech platforms and border agencies, the fraud economy adapts faster than it is disrupted.

What to Know

- Chinese courts sentenced top members of the Bai and Ming Kokang families to death, with others receiving life terms and long prison sentences.

- Judges found that one network built 41 compounds for casinos and cyber fraud that generated more than 29 billion yuan, and that violence inside led to deaths and injuries.

- Authorities say more than 53,000 Chinese suspects tied to northern Myanmar compounds have been returned to China since the campaign began.

- Joint actions by China, Myanmar and Thailand freed thousands of workers near Myawaddy. One wave released more than 7,000 people, with later operations pushing totals higher.

- China and regional partners launched the Jingyao operation. Officials reported more than 70,000 arrests across multiple countries and 160 rescues in its first phase.

- Syndicates have relocated from Laukkaing to KK Park, Shwe Kokko and deeper into Shan State, and some have spread to cities such as Yangon and Mandalay.

- Local militias, including the Karen Border Guard Force and the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army, have been identified by governments as facilitators of some hubs, though the BGF denies trafficking involvement.

- Hundreds of thousands of people are believed to be working in scam centers globally, many under coercion or trafficking conditions.

- Compounds use satellite internet, solar power and cryptocurrency networks to keep operations running and move money quickly.

- Police worldwide report losses in the tens of billions of dollars a year, with estimates around 10 billion dollars in the United States alone for related frauds.