A decade of tightened control and rising fear

North Korea has widened its use of the death penalty and deepened social control over daily life, according to a new review by the United Nations human rights office. Based on more than 300 interviews with people who escaped the country in the past decade, the report describes a state where surveillance has expanded, punishments have grown harsher, and access to information is policed with extraordinary zeal. Witnesses described public executions by firing squad and a sharp rise in cases tied to foreign information, especially the sharing of films and television series from abroad.

- A decade of tightened control and rising fear

- What changed in North Korean law

- How public executions and trials enforce compliance

- Surveillance, technology, and the crackdown on information

- Forced labor and shock brigades

- Food insecurity, markets, and border control

- Political prison camps and detention today

- International accountability faces a wall

- The Bottom Line

The UN review concludes that North Korea stands apart for the breadth of restrictions on its people, from what they can watch or say to how they work, travel, and trade. Interviewees recounted a clear tightening that accelerated after 2019 and through the Covid period, with the state focusing its energy on sealing borders, intensifying ideological indoctrination, and cutting the few remaining channels through which outside culture and news reached ordinary citizens. The report says the legal and practical use of the death penalty has expanded, and that public trials and executions are used to instill fear and enforce compliance.

The document follows the landmark 2014 UN Commission of Inquiry that found crimes against humanity, including torture, forced starvation, and extensive political prison camps. A decade later, at least four political prison camps continue to operate, and detainees in ordinary prisons still face abuse and malnutrition, the UN says. While a few witnesses cited modest improvements in detention, such as slightly less violence by some guards, these changes are overshadowed by broader deterioration in economic rights, freedom of expression, and basic personal autonomy.

The UN high commissioner for human rights, Volker Turk, warned that the pattern points to even harsher conditions without strong external pressure and internal reform.

"If the DPRK continues on its current trajectory, the population will be subjected to more suffering, brutal repression and fear," said Volker Turk, the UN human rights chief.

What changed in North Korean law

Since 2015, the government has adopted new laws and practices that broaden the scope for severe punishment, including capital punishment, for a wider set of acts. These measures include provisions that criminalize anti state propaganda and the dissemination of unauthorized information. Witnesses and experts told UN investigators that these statutes have been used to justify prison terms, forced labor, and, in some cases, execution. The report emphasizes that legal changes, administrative decrees, and intensified policing have worked together to give authorities wider discretion to label ordinary behavior as hostile to the state.

From watching to distributing foreign media

The harshest penalties fall on distribution. The UN says people have been executed for sharing or selling foreign movies and television series, including popular South Korean dramas. Interviewees described how cases tied to foreign content surged from 2020, when border closures and heightened inspections pushed the state to treat outside media as a direct threat to regime control. While possession or viewing can bring severe punishment, distribution has drawn the most extreme responses, including public executions.

Enforcement is active and often invasive. Witnesses reported door to door searches, surprise checks of computers and phones, and the inspection of storage devices. Such operations, framed as campaigns against anti socialist behavior, have contributed to a climate in which people censor themselves at home, at work, and among friends.

How public executions and trials enforce compliance

Public trials and executions serve a clear purpose in this system. Multiple interviewees said authorities summon local residents, students, and work units to attend proceedings and executions. The intent is to demonstrate the cost of defiance, solidify social obedience, and cut off the circulation of ideas or culture deemed hostile. Accounts gathered by the UN describe rows of residents lined up to witness a firing squad, after a brief proceeding in which guilt is declared and a sentence read aloud.

One escapee, Kang Gyuri, who fled in 2023, said she attended the trial of a 23 year old friend who was sentenced to death after being caught with South Korean videos. She described a system that now treats media offenses on par with crimes that would traditionally draw the most severe punishments.

"He was tried along with drug criminals. These crimes are treated the same now," said escapee Kang Gyuri, adding that fear deepened from 2020.

Several witnesses told investigators they saw more executions after 2020 linked to distribution of foreign media, as well as drug cases and certain business offenses. The UN report notes that the state sometimes organizes such events to coincide with larger propaganda campaigns, heightening the spectacle and its deterrent value.

Surveillance, technology, and the crackdown on information

Technology has strengthened state control. Interviewees described routine checks of mobile phones, memory cards, and laptops, along with the monitoring of communication tools inside workplaces and schools. The country maintains a national intranet reserved for approved institutions and officials. Ordinary people have almost no access to the global internet. The UN report says that surveillance touches every part of life, aided by new tools and tightened rules that reach into homes and private circles.

Social pressure reinforces this digital net. Citizens are expected to join weekly self criticism sessions that demand confession of faults and the denunciation of neighbors. The sessions function as collective surveillance and ideological conditioning, according to witness testimonies. Together with expanded police powers to search and seize, these practices have made the private consumption of ideas, music, language, and film more dangerous.

Blocking eyes and ears

Witnesses told UN researchers that the goal is not only to stop the flow of content but to silence dissatisfaction before it can form.

"To block the people's eyes and ears, they strengthened the crackdowns. It was a form of control aimed at eliminating even the smallest signs of dissatisfaction or complaint," said one escapee who requested anonymity.

Authorities have also targeted vocabulary and expressions seen as foreign or ideologically impure, alongside the media itself. People described inspections that extend to radios preset to state stations and televisions set to fixed channels, as well as neighborhood checks focused on slang and speech linked to South Korean pop culture.

Forced labor and shock brigades

The report describes a wider use of forced labor across the country. People from poor families are conscripted into so called shock brigades for physically demanding projects such as coal mining, road building, and construction. Children, including orphans and those from families without resources, are drawn into hard labor where injuries and deaths are common. The UN says these practices can meet the threshold of slavery when participation is compulsory and conditions are hazardous.

James Heenan, who heads the UN human rights office focused on North Korea, said the burden falls most heavily on vulnerable groups, including children who cannot buy their way out of conscription.

"They are often children from the lower level of society, because they are the ones who can't bribe their way out of it, and these shock brigades are engaged in often very hazardous and dangerous work," said James Heenan of the UN human rights office for DPRK.

Interviewees said deaths in these brigades are publicly glorified as sacrifices to the leader, rather than prompting safety reforms. The state also relies on forced labor inside the prison and military systems, requiring long hours and exposing people to dangerous materials. The UN says these practices have persisted for years, even as the government has passed some laws that appear on paper to strengthen fair trial guarantees.

Food insecurity, markets, and border control

Economic hardship runs through the testimonies. Most interviewees said three meals a day was a luxury for their families. Many remembered the Covid period as a time of acute shortages, when border closures severed trade routes that had quietly supplemented government distribution. People described neighbors and relatives losing weight quickly, going without protein for long stretches, or dying after prolonged hunger.

At the same time, the state tightened control of informal markets, reducing a crucial lifeline that had emerged over the past two decades. Crackdowns on small traders, seizures of goods, and restrictions on travel between regions limited families’ ability to earn income independently. Border defense units were ordered to stop crossings to China, and witnesses said some troops were told to shoot people trying to escape. Fewer people were able to flee, and the supply of smuggled food, medicine, and media dwindled.

Several interviewees said they had hoped for better prospects when Kim Jong Un took power in 2011, after pledges to improve living standards. Those hopes faded as diplomacy with the United States and other powers stalled from 2019, while the state prioritized weapons development and internal control.

Political prison camps and detention today

At least four political prison camps remain in operation, according to the UN report, and the prison system still features torture, forced labor, and malnutrition. Witnesses spoke of inmates collapsing from exhaustion and disease, with burials carried out without notice to families. Investigators did hear about limited improvements in some detention centers, such as a slight decrease in beatings by guards. North Korea has also ratified two more human rights treaties in recent years. Still, the UN says practices on the ground remain far from international standards, and legal changes that look positive on paper have not translated into meaningful rights protections.

Witnesses also noted a rise in executions since 2020 for a range of offenses, including distribution of foreign media, drug cases, trafficking, prostitution, and some violent crimes. The return of public trials and execution events since the pandemic years has reinforced the climate of fear documented across regions and social classes.

International accountability faces a wall

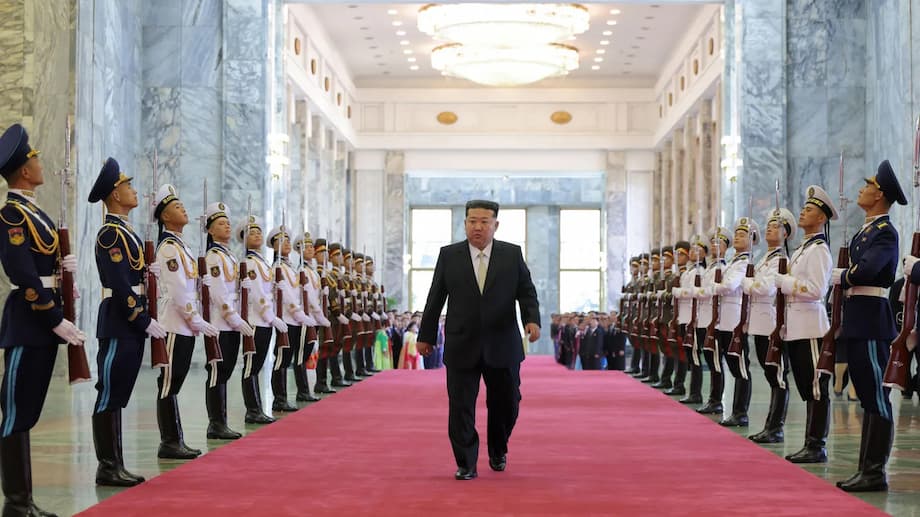

The UN human rights office has urged that North Korea’s situation be referred to the International Criminal Court in The Hague. That step would require a vote in the UN Security Council, where permanent members can veto. Efforts to advance new measures aimed at accountability have met resistance, and attempts to tighten international pressure on Pyongyang have been blocked repeatedly. The diplomatic challenge has grown as ties between North Korea, China, and Russia have become more visible, including a recent military parade appearance in Beijing by Kim Jong Un alongside Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin.

North Korea rejects UN mandates that authorize these investigations and denies rights violations. The UN continues to press for concrete steps from Pyongyang, including the abolition of political prison camps, the end of executions, and the introduction of human rights education inside the country. Interviewees, especially younger escapees, expressed a strong desire for change in how the state treats its people and how information flows, even as immediate prospects for reform remain constrained by politics at home and abroad.

The Bottom Line

- UN investigators say executions have increased, including for distributing foreign media such as South Korean dramas.

- Since 2015, at least six new laws expanded grounds for severe punishment, including the death penalty.

- Public trials and executions are used to deter, with witnesses describing firing squad executions after brief proceedings.

- Surveillance has intensified through device inspections, limited internet access, and weekly self criticism sessions.

- Forced labor, including shock brigades, involves children and orphans in hazardous work where deaths are common.

- Food shortages worsened during the Covid period as borders closed and informal markets faced crackdowns.

- At least four political prison camps remain active, with torture, overwork, and malnutrition still reported.

- The UN urges a referral to the International Criminal Court, but action requires Security Council approval that has been blocked.

- Officials report a strong desire for change among younger North Koreans, despite mounting risks and tighter control.