Bangkok’s Latest Crackdown on Street Vendors: A New Era for City Footpaths

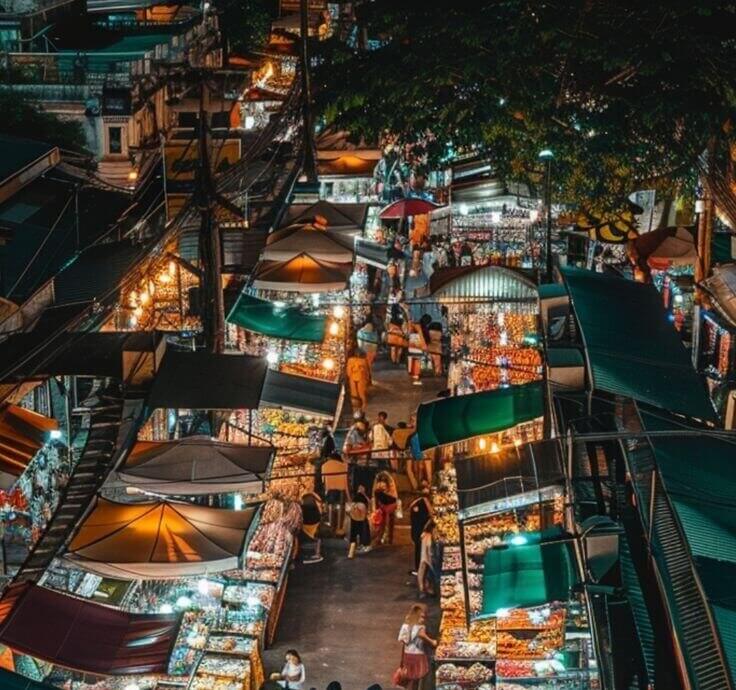

Bangkok, a city renowned for its vibrant street food culture and bustling sidewalk commerce, is undergoing a significant transformation. In 2025, the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) has intensified its efforts to regulate street vendors, aiming to reclaim public spaces, ensure pedestrian safety, and elevate urban cleanliness. This sweeping initiative, led by Deputy Governor Jakapun Phiwngam, marks a pivotal moment in the ongoing debate over the future of Bangkok’s iconic street life.

- Bangkok’s Latest Crackdown on Street Vendors: A New Era for City Footpaths

- Why the Crackdown? The Push for Order and Cleanliness

- Designated Zones and the Shrinking Space for Vendors

- Case Study: Pathumwan District and the Human Impact

- The Singapore Model: Inspiration and Limitations

- Vendor Perspectives: Livelihoods at Stake

- Public Opinion: Divided Over the Future of Street Food

- Regulatory Details: Who Can Be a Vendor?

- Broader Urban Initiatives: Beyond Street Vendors

- Cultural and Economic Implications: What’s at Stake?

- In Summary

At the heart of the new policy is a strict directive: vendors must thoroughly clean pavements daily after closing their stalls. The BMA’s approach is multifaceted, involving the reduction of designated vending zones, stricter enforcement of hygiene standards, and the relocation of vendors to regulated areas. These measures are reshaping the city’s commercial landscape, sparking both support and concern among residents, business owners, and international observers.

Why the Crackdown? The Push for Order and Cleanliness

The BMA’s crackdown is rooted in a desire to address long-standing issues associated with unregulated street vending. For decades, Bangkok’s pavements have been crowded with food carts, makeshift stalls, and vendors selling everything from noodles to souvenirs. While this has contributed to the city’s unique charm and economic vitality, it has also led to complaints about blocked sidewalks, unsanitary conditions, and safety hazards for pedestrians.

Deputy Governor Jakapun Phiwngam emphasized the importance of maintaining order in commercial areas, stating that district directors and Tessakit (municipal law enforcement) chiefs across all 50 districts play a crucial role in implementing the BMA’s policies. The new regulations require vendors to:

- Clean their trading areas daily after business hours or every Monday (a designated non-trading day)

- Install grease traps and regularly wash utensils and equipment at food stalls

- Maintain proper vendor registration, including ID cards and QR codes

These measures are designed to ensure that commercial zones adhere to criteria set for 2024 and beyond, with the ultimate goal of making Bangkok’s streets safer and more accessible for everyone.

Designated Zones and the Shrinking Space for Vendors

One of the most significant changes under the new policy is the reduction in the number of “lenient zones”—areas where street vending is officially permitted. In 2022, Bangkok had 86 such zones accommodating 4,500 vendors, alongside 741 unregulated trading spots with nearly 17,000 vendors. By 2025, the number of lenient zones has dropped to 59, with just 3,771 vendors, and non-lenient trading areas have been reduced to 321 spots with 9,920 vendors.

This contraction is the result of a rigorous evaluation process. A three-tiered committee, including district officials, sanitation and environmental departments, vendor representatives, and BMA inspectors, conducts monthly assessments of commercial areas. Only those that meet strict criteria—such as public consultation, safety, and hygiene standards—are approved as official trading zones. Areas that fail to comply face legal enforcement, including the revocation of trading permits.

District offices can propose “unique identity areas” that may be exempt from standard criteria, allowing for some flexibility in preserving local character. However, the overall trend is clear: the city is moving toward fewer, more tightly regulated vending spaces.

Case Study: Pathumwan District and the Human Impact

The impact of the crackdown is particularly evident in districts like Pathumwan, a commercial hub near the Erawan Shrine and Siam Square. In early 2025, the BMA cancelled street vending at two key locations—Ton Son on Ploenchit Road and the area in front of the Siam Scape building—displacing 26 vendors. Officials are also working with flower vendors near the Erawan Shrine to reorganize public space and minimize traffic disruptions.

Currently, Pathumwan has 13 areas where 222 vendors are permitted to operate, down from previous years. Two hawker centres have been established at Lumpini Park Gate 5 and Ratchadamri intersection, accommodating 122 vendors. This approach mirrors Singapore’s model of relocating street vendors to designated food centres, a strategy praised for its cleanliness and order but sometimes criticized for eroding the spontaneity and accessibility of street food culture.

Deputy Governor Jakkapan Phiewngam and BMA officials have conducted inspections to ensure compliance, urging vendors to confine their stalls to authorized areas and maintain high standards of hygiene. Violators face fines of up to 2,000 baht, and repeat offenders risk losing their permits altogether.

The Singapore Model: Inspiration and Limitations

Bangkok’s strategy draws inspiration from Singapore, where the government successfully relocated street hawkers to purpose-built centres, now recognized as part of the country’s intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO. The BMA hopes to replicate this success by creating regulated spaces that balance economic opportunity with public order.

However, experts caution that the Singapore model may not be fully transferable to Bangkok. The Thai capital’s street food scene is deeply intertwined with its social fabric, providing affordable meals for millions and serving as a vital source of income for low-income families, many of whom are women and rural migrants. According to estimates, as much as 2% of Bangkok’s population is involved in street vending—a figure that makes complete relocation a daunting challenge.

Kessara Thanyalakpark, the governor’s chief strategy and financial adviser, explained that the BMA is developing criteria for new off-street premises, with priority given to existing vendors and those earning less than 360,000 baht per year. The goal is to provide sustainable jobs and affordable food, not to eliminate street vending altogether.

Vendor Perspectives: Livelihoods at Stake

For many vendors, the crackdown represents an existential threat. Relocation to less favorable locations often means reduced foot traffic and lower sales, jeopardizing their ability to support their families. Some vendors have chosen to return to their hometowns, while others risk fines by continuing to operate in prohibited areas.

Lewan Choptha, a souvenir stall owner and leader of the Network of Thai Vendors for Sustainable Development, voiced the concerns of many:

“They can clean up the streets but please don’t get rid of us entirely.”

Vendors and advocacy groups have called for fair treatment and greater support, arguing that street vending is not only a source of affordable food but also a crucial part of Bangkok’s cultural identity. Professor Narumol Nirathron of Thammasat University found that 87% of surveyed residents regularly buy from street vendors, highlighting their importance to both low-income earners and the broader public.

Public Opinion: Divided Over the Future of Street Food

The crackdown has sparked a lively debate among Bangkok residents, tourists, and international observers. Supporters argue that the measures are necessary to address overcrowding, improve hygiene, and make the city more accessible. Critics, however, warn that the loss of street food culture could diminish Bangkok’s unique character and harm its appeal as a global tourist destination.

David Thompson, an Australian chef and Thai food expert, captured the sentiment of many food lovers:

“I’ve never met such a people who eat so much, who think about food so much – it’s the national pastime, frankly. Having food on the streets means they’re able to do that.”

International media have also weighed in, noting that Bangkok’s street food is regularly cited as the world’s best and is a major draw for visitors. The New York Times and South China Morning Post have both highlighted the tension between modernization and the preservation of culinary heritage.

Regulatory Details: Who Can Be a Vendor?

The BMA’s new rules are designed to ensure that only “poor Thais” are eligible to operate as street vendors. Applicants must be Thai citizens and meet at least one of three requirements: holding a state welfare card, participating in the Baan Mankong housing scheme, or receiving welfare aid from the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security. In the second year, vendors must prove their annual income does not exceed 300,000 baht, as shown by tax filings.

Stalls are limited to three square metres, must not obstruct public areas such as bus stops or footbridges, and must leave at least 1.5 to 2 metres of space for pedestrians. In areas where demand exceeds available space, a lottery system is used to allocate spots. The BMA reviews the suitability of vending areas every one or two years, adjusting policies as needed to balance economic and urban planning goals.

Broader Urban Initiatives: Beyond Street Vendors

The BMA’s efforts extend beyond street vending. Officials are also addressing issues such as abandoned vehicles, illegal waste dumping, and motorcyclists riding on pavements. From 2020 to mid-2025, over 1,600 abandoned vehicles were identified, with most removed by their owners or relocated by district offices. Fines and auctions have generated additional revenue for the city, and ongoing enforcement aims to keep public spaces clean and safe.

Technology is playing a role as well. The BMA has deployed AI camera systems to catch traffic violations and monitor compliance with new regulations. These initiatives are part of a broader push to modernize Bangkok and enhance its livability for residents and visitors alike.

Cultural and Economic Implications: What’s at Stake?

Bangkok’s street food is more than just a culinary attraction—it is a social equalizer, a source of affordable nutrition, and a symbol of the city’s resilience and creativity. The tradition dates back over a century, with roots in Chinese immigrant communities and a history of adaptation to changing economic and social conditions.

As the city moves toward a more regulated future, questions remain about the long-term impact on vendors, consumers, and the urban landscape. Will hawker centres and designated zones preserve the spirit of street food, or will they lead to a sanitized, less accessible version of Bangkok’s famed culinary scene? Can the city balance the needs of pedestrians, vendors, and tourists without sacrificing its unique identity?

For now, the answer is uncertain. While some areas have successfully transitioned to new models, others have seen a decline in business and a loss of vibrancy. The BMA’s ongoing evaluations and willingness to adapt policies suggest that the story is far from over.

In Summary

- Bangkok’s BMA has intensified its crackdown on street vendors, focusing on daily pavement cleaning, reduced vending zones, and stricter hygiene standards.

- The number of designated vending areas has been significantly reduced, with many vendors relocated to hawker centres or off-street premises.

- New regulations prioritize low-income Thai citizens and set strict criteria for vendor eligibility, stall size, and location.

- The crackdown has sparked debate over the balance between urban order, economic opportunity, and the preservation of street food culture.

- Vendor livelihoods, public opinion, and the city’s global reputation as a street food capital are all at stake as Bangkok navigates this complex transition.

- The BMA continues to review and adapt its policies, aiming to create a cleaner, safer, and more organized city while maintaining its unique character.