The Hidden Burden: Plastic Pollution in Rural Bangladesh

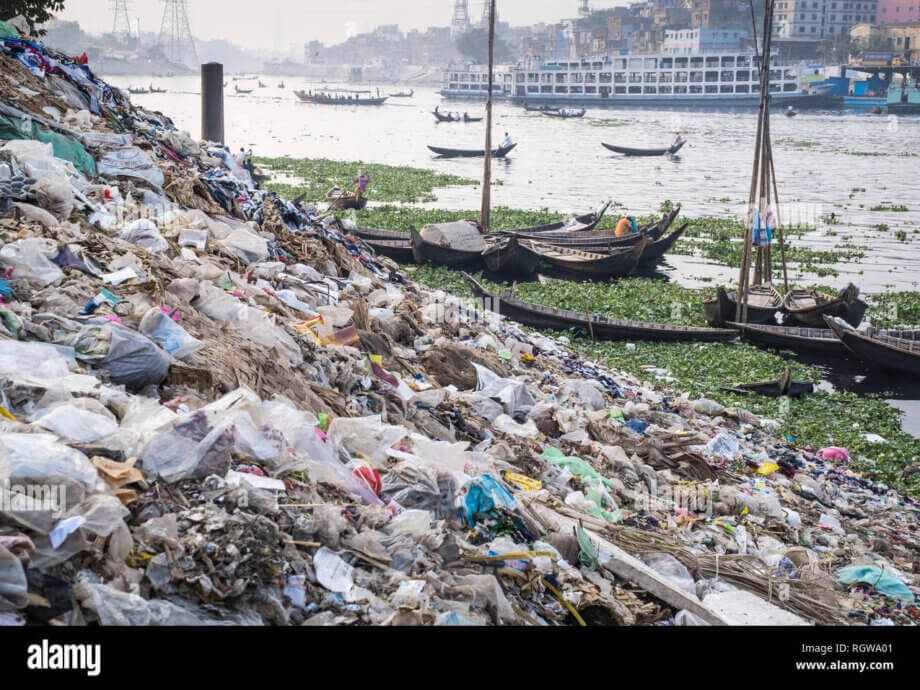

Plastic pollution is often seen as an urban problem, with images of overflowing bins and clogged city drains dominating headlines. Yet, in Bangladesh, the crisis extends far beyond the bustling streets of Dhaka and Chattogram. In the country’s rural and peri-urban areas, plastic waste is silently but severely disrupting daily life, livelihoods, and the environment. The story of Sumon, a tea stall owner who wades through ankle-deep plastic waste each morning, is emblematic of a much larger, largely overlooked crisis.

- The Hidden Burden: Plastic Pollution in Rural Bangladesh

- How Plastic Pollution Impacts Rural Life

- Why Rural Areas Are Especially Vulnerable

- Health and Environmental Risks: Beyond the Visible

- Why Solutions Have Fallen Short

- Grassroots Innovations and Community Action

- Policy, Partnerships, and the Path Forward

- Case Study: Cox’s Bazar and the Power of Collaboration

- What Needs to Happen Next?

- In Summary

While cities generate the bulk of Bangladesh’s plastic waste, rural regions are increasingly bearing the brunt. An estimated 87,000 tonnes of single-use plastic waste are produced annually in Bangladesh, with nearly 22 percent originating from rural areas. The consequences are visible in blocked irrigation channels, waterlogged fields, and polluted rivers—threatening agriculture, health, and the sustainability of rural communities.

How Plastic Pollution Impacts Rural Life

Plastic waste in rural Bangladesh is not just an eyesore; it is a direct threat to the environment and the people who depend on it. Discarded bottles, wrappers, and bags accumulate in open spaces, clogging drains and irrigation channels. When it rains, these blockages cause markets and fields to flood, disrupting business and farming activities. For farmers, plastic mixed with crop residues can starve crops of vital water, while debris around sluice gates worsens persistent waterlogging.

Unlike urban areas, where some waste management infrastructure exists, rural communities often lack even basic collection services. There are no designated dumping areas, and plastic is frequently discarded wherever it is used. This mismanagement leads to plastic infiltrating rivers, canals, and croplands, with long-term consequences for soil fertility and water quality. Microplastics—tiny fragments resulting from the breakdown of larger items—are now being detected in water, soil, and even human blood, raising serious health concerns.

According to a 2024 study by the Environment and Social Development Organisation (ESDO), Bangladesh uses up to 3.84 billion single-use plastic bottles annually, with only 21.4 percent recycled. The rest end up in landfills, rivers, and the sea, where they can persist for up to 450 years, releasing toxic chemicals and microplastics into the ecosystem and food chain.

Why Rural Areas Are Especially Vulnerable

Several factors make rural Bangladesh particularly susceptible to the impacts of plastic pollution:

- Lack of Awareness: Only 5.5 percent of rural consumers are aware of the health risks posed by single-use plastics, compared to 18.4 percent in urban areas. This knowledge gap leads to widespread improper disposal and reuse of plastic items.

- Absence of Waste Management Infrastructure: Most rural areas lack formal waste collection, segregation, or recycling services. Plastic waste is often burned, buried, or dumped in open spaces, exacerbating environmental and health risks.

- Changing Consumption Patterns: The proliferation of packaged goods and single-use plastics has altered traditional lifestyles. Where once people used baskets made of cane or bamboo, single-use polythene bags and plastic packaging are now the norm, even in remote villages.

- Limited Enforcement of Regulations: Despite a national ban on plastic bags in 2002, enforcement has been weak, especially outside major cities. The use of single-use plastics has increased by 200 percent over the last decade, with rural areas increasingly affected.

These vulnerabilities are compounded by the fact that rural communities often depend directly on natural resources for their livelihoods. When plastic pollution disrupts agriculture, fisheries, or water supplies, the economic and social impacts are immediate and severe.

Health and Environmental Risks: Beyond the Visible

The dangers of plastic pollution go far beyond blocked drains and unsightly litter. As plastics degrade, they release microplastics and toxic chemicals such as Bisphenol A (BPA), which can contaminate soil, water, and food. These substances have been linked to hormonal disruption, cancer, and other long-term health issues.

Microplastics are now being detected in the food chain, including in fish and crops consumed by rural populations. The health risks are compounded by a lack of awareness and limited access to healthcare in many rural areas. As Dr. Md Abul Hashem, a senior technical adviser to ESDO, warns:

“The risks associated with chemicals like BPA and microplastics cannot be ignored as they infiltrate our food chain and harm biodiversity.”

Environmental impacts are equally alarming. Plastic waste blocks irrigation channels, reducing water flow to crops and contributing to soil degradation. In the rainy season, blocked drainage systems lead to severe waterlogging and flooding, increasing the spread of waterborne diseases. The Bay of Bengal, fed by Bangladesh’s rivers, is now a major recipient of inland plastic waste, threatening marine life and coastal ecosystems.

Why Solutions Have Fallen Short

Bangladesh has not ignored the plastic crisis. The country was the first in the world to ban plastic shopping bags in 2002, and several policies and regulations have since been introduced, including the Plastic Waste Management and Conservation Rules (2008) and the Jute Packaging Act (2010). More recently, bans on single-use plastics in supermarkets and coastal areas have been announced.

However, these measures have struggled to make a significant impact, especially in rural areas. The reasons are complex:

- Weak Enforcement: Laws are often poorly implemented, with limited monitoring and few penalties for violations.

- Lack of Alternatives: Affordable, accessible alternatives to single-use plastics are not widely available, making it difficult for consumers and businesses to change their habits.

- Resource Constraints: Local governments, especially union parishads and municipalities, often lack the technical capacity, funding, and structured plans needed to manage plastic waste effectively.

- Limited Public Engagement: Without widespread awareness and community involvement, even the best policies can fail to change behavior.

As a result, only about 36 percent of plastic waste in Bangladesh is recycled, with the rest accumulating in open dumps, water bodies, and agricultural lands.

Grassroots Innovations and Community Action

Despite these challenges, there are signs of hope. Small-scale and community-driven initiatives are emerging as potential game changers in the fight against rural plastic pollution.

- Informal Sector Contributions: The informal sector collects around 1,000 tonnes of plastic waste daily, playing a crucial role in recycling efforts. However, their impact is limited by a lack of formal recognition, support, and access to resources.

- Plastic Exchange Programs: In Dhaka, Standard Chartered Bank has launched a program allowing community members to trade plastic waste for cash or essentials. Replicating such initiatives in rural areas could incentivize waste collection and create local income opportunities.

- Market-Centric Collection Hubs: Development platforms are working with the private sector to establish collection hubs that incentivize traders to segregate and deposit plastic waste for recycling. These hubs can foster a culture of environmental responsibility, even in areas with limited infrastructure.

- Innovative Recycling: In Faridpur, Practical Action employs a circular economy approach, processing low-grade plastics from the Padma River into high-grade oil and black carbon using pyrolysis technology. This not only reduces waste but also creates jobs and improves livelihoods for waste workers.

Educational programs are also making a difference. In Cox’s Bazar, school collection systems teach children about waste segregation and composting, instilling sustainable habits from an early age. The WaterAid–Swisscontact consortium has engaged students in clean-up campaigns and educational activities in climate hotspots like Naogaon and Satkhira, demonstrating the power of early intervention.

Policy, Partnerships, and the Path Forward

Experts and policymakers agree that no single solution will suffice. Instead, a comprehensive, multi-stakeholder approach is needed—one that combines regulation, innovation, education, and community engagement.

Strengthening Legislation and Enforcement

Existing laws must be enforced more rigorously, with stricter penalties for violations and better monitoring. New regulations may be needed to address emerging challenges, such as the proliferation of single-use plastics and transboundary plastic pollution from upstream countries. Bangladesh’s participation in international agreements, like the Basel Convention and the forthcoming Global Plastic Treaty, can help address cross-border issues.

Promoting Sustainable Alternatives

Affordable, eco-friendly alternatives to single-use plastics are essential. The “Sonali Bag,” made from jute cellulose and invented by Bangladeshi scientist Dr. Mubarak Ahmad Khan, is a promising example. Promoting reusable bags, biodegradable packaging, and traditional materials can help shift consumer behavior, but these alternatives must be accessible and cost-competitive.

Investing in Waste Management Infrastructure

Improving waste collection, segregation, and recycling facilities is critical, especially in rural areas. Public-private partnerships can mobilize resources and expertise, while green finance initiatives—such as those supported by Bangladesh Bank—can fund environmentally responsible investments. The Coca-Cola Foundation’s $15 million grant to the United Nations Development Programme for plastic waste management in Asia, including Bangladesh, highlights the potential of international funding and collaboration.

Engaging Communities and the Informal Sector

Community participation is vital. Awareness campaigns, school programs, and local clean-up drives can foster a culture of environmental stewardship. The informal sector, including waste pickers and recyclers, should be integrated into formal waste management systems through training, support, and recognition.

Fostering Innovation and Research

Bangladesh’s youth and entrepreneurs are already developing innovative solutions, from floating waste-cleaning robots to digital platforms that incentivize recycling. Supporting research and innovation in sustainable materials and waste management technologies can drive long-term change.

Case Study: Cox’s Bazar and the Power of Collaboration

Cox’s Bazar, a coastal municipality and major tourist destination, illustrates both the challenges and opportunities of rural plastic waste management. According to a 2024 BRAC study, 34.5 tonnes of plastic waste are mismanaged daily in the municipality, much of it ending up in canals, drains, and the sea. Only 18 percent of the population practices waste segregation at source, and formal collection services are limited.

In response, the Plastic Free Rivers and Seas for South Asia (PLEASE) project, funded by the World Bank and supported by multiple partners, is piloting innovative solutions. These include communal bins, a proposed recycling facility, and the promotion of recycled and upcycled products by local green entrepreneurs. The project has already achieved a 15 percent improvement in source segregation and noticeable reductions in plastic waste hotspots.

At a recent national dialogue, AKM Tariqul Alam, Additional Secretary of the Local Government Division, emphasized the importance of preventing plastic waste from flowing downstream into the sea by strengthening systems that intercept waste along rivers and streams. He highlighted the need to scale up both international best practices and locally-led innovations.

“Bangladesh can benefit from both studying international best practices and scaling up homegrown, locally-led innovations in waste management,” said AKM Tariqul Alam.

Such cross-sectoral coordination—bringing together government, municipalities, the private sector, and communities—is essential for sustainable progress.

What Needs to Happen Next?

To effectively tackle plastic pollution in rural and peri-urban Bangladesh, isolated initiatives are not enough. Experts and stakeholders recommend a series of mutually reinforcing strategies:

- Support Local Governments: Provide targeted funding, technical training, and structured plans to help union parishads and municipalities incorporate plastic waste management into local development agendas.

- Promote Waste Segregation and Community Hubs: Encourage waste segregation at the source and establish community-based recycling hubs to lay the groundwork for structured waste management systems.

- Empower Local Entrepreneurs: Offer technical training and seed funding to help local entrepreneurs establish small recycling units, producing useful products like eco-bricks or compost bins.

- Expand Education and Awareness: Integrate environmental education into school curricula and community programs, using creative approaches to build plastic literacy from a young age.

- Leverage Public-Private Partnerships: Mobilize resources and expertise from the private sector, NGOs, and international donors to build infrastructure, promote innovation, and scale up successful models.

- Strengthen Policy and International Cooperation: Enforce existing regulations, develop new policies as needed, and participate actively in international efforts to address transboundary plastic pollution.

Ultimately, the fight against plastic pollution in Bangladesh is not just about cleaning up waste—it is about transforming mindsets, systems, and economies. With the right support, rural communities can move from being passive victims to active change-makers, driving local recycling initiatives, championing waste reduction, and adopting sustainable practices.

In Summary

- Plastic pollution in rural Bangladesh is a growing crisis, with severe impacts on agriculture, health, and the environment.

- Rural areas face unique challenges, including lack of awareness, inadequate waste management infrastructure, and weak enforcement of regulations.

- Plastic waste blocks irrigation channels, causes flooding, and introduces toxic chemicals and microplastics into the food chain.

- Existing policies and bans have had limited impact due to poor enforcement and lack of affordable alternatives.

- Grassroots initiatives, community engagement, and innovative recycling projects are emerging as effective solutions.

- Comprehensive action is needed: stronger legislation, investment in infrastructure, education, public-private partnerships, and international cooperation.

- With coordinated efforts, rural communities can become leaders in the fight against plastic pollution, ensuring a cleaner, healthier, and more sustainable future for Bangladesh.